Benedictine Life

A Day in the Life of a Benedictine Monk

Our day begins at 3:10 a.m. with the wake-up bell. After a small cup of coffee, the brothers quietly make their way to the chapel for Vigils, the longest office of the day. Over the course of an hour, we chant fourteen Psalms and listen to two long readings, one from the Scriptures and a second from the Church Fathers.

We join the angels, who never sleep, in watching for the coming of Jesus Christ in glory to save those who eagerly are waiting for Him.

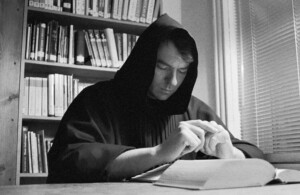

This communal prayer is followed by a period of private prayer called lectio divina. This is a traditional prayerful meditation on God’s Word, particular the Holy Scriptures.

At 6:00 a.m., we return to the chapel for the office of ‘Lauds’, our morning praise of God.

This is followed directly by the celebration of Holy Mass, with traditional Gregorian chant. We sing most of the offices in English and most of the Mass in Latin.

After Mass, there is a short period for personal matters and breakfast.

At 8:15 a.m., we gather in the Chapter Room, where the Prior reads from the Rule of Saint Benedict and gives a short commentary applying its sixth-century text to our contemporary situation. We then have a few moments to discuss together our work for the day.

Strengthening the Spirit

After Chapter, we have classes each day, on liturgy, Scripture, the Tradition, moral and spiritual theology, the vows, and other topics important to deepening our monastic life.

At 9:30 a.m., we return to the chapel for the office of Terce. When this concludes, we begin the main work period of the day.

Monastic work is preferably humble and manual, though it also includes intellectual work of study and the preparation of classes, homilies, and conferences.

Our work in hospitality means that cooking and cleaning occupy a good portion of the brothers’ mornings.

Our work in hospitality means that cooking and cleaning occupy a good portion of the brothers’ mornings.

We also have a large garden. We do not employ any outside help for the daily work of cooking or keeping the cloister clean and in good repair.

At 12:45 p.m. the work period ends, and we gather for the midday office of Sext.

This is followed by the main meal of the day, in silence, with table reading. The reading is typically something of interest in the monastic life, but we also enjoy books on history and biography.

The main meal is served by one or two of the brothers. The community does the dishes, and then we have about an hour for a siesta or other personal matters.

At 2:30 p.m., we pray the office of None.

This is followed by shorter classes, either chant or languages (Latin, Greek or French). The rest of the afternoon is usually used for exercise, practicing musical instruments, or reading.

Vespers

Vespers is a solemn office each day, beginning at 5:15 p.m. with a short procession. On Sundays and major feasts, we also use incense and vestments to mark the solemnity of the office. It is a particularly beautiful time of day in our church, with the setting sun streaming through the golden Magnificat window in the choir loft.

Once a month the Monastery hosts its resident choral group, Schola Laudis, for the celebration of Solemn Vespers. The goal of the Schola is two-fold: to enrich the liturgical life of the Monastery and the Archdiocese of Chicago by the incorporation of the masterworks of the Renaissance composers, and more generally, to help introduce more people to the beauty of the Catholic liturgical tradition. For more information, click here.

Vespers is followed by a light optional meal called ‘collation’.

After the meal, brothers have some time of their own again, though three nights a week we have recreation, and one of those nights, the Prior also gives a longer spiritual conference.

Compline follows at 7:15 p.m., ending with the great antiphon to Our Lady, either the Salve Regina (during Ordinary Time) or another antiphon varying by season.

Ideally, the monks return to their cells and prepare to retire for the night. Often, there is some reading to be done in preparation for the next day’s classes, and this quiet time of night is also ideal for personal prayer.

Sundays follow a slightly different schedule. We try to refrain from manual labor and to keep a greater silence. The liturgies are a bit longer and more solemn. At Mass, we normally have about 40 guests and we sing more polyphony.

In the evening we have a recreational meal—the one meal of the week where we visit with one another.

Our Spirituality

The Benedictine way of life has its roots in the fourth-century Egyptian desert, where many men and women fled the world to seek God in a radical life of poverty, silence and prayer.

A monk of the late fourth-century, Saint John Cassian, wrote down the essential teachings of the ‘Desert Fathers’ in two highly influential books, The Institutes and The Conferences. These books were commissioned by Pope Damasus for the purpose of founding monastic life in the Europe of the time.

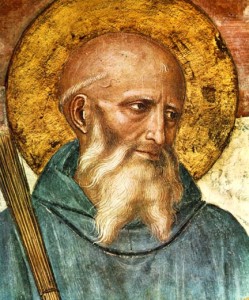

Three generations after Cassian, Saint Benedict of Nursia, disillusioned by dissolute student life in Rome, withdrew from the world to the cave of Subiaco fifty miles north of the city.

There, disciples began to attach themselves to him. Under the influence of Cassian’s teachings, he wrote his Rule for Monks, and it is this sixth-century text that still founds the basis of our spirituality.

The Institutes concern themselves with the reform of our behavior and our thoughts, without which there can be no genuine spiritual growth.

The Desert Fathers’ insights on the working of the mind were first systematized by Cassian’s teacher, Evagrius of Pontus. He taught that any thought that tempts us toward sin falls into one of eight broader categories: lust, gluttony, avarice, anger, sadness, spiritual lethargy (acedia), vainglory and pride. This teaching eventually became the basis for the ‘Seven Capital Sins’ of later, secular spirituality.

The Desert Fathers’ insights on the working of the mind were first systematized by Cassian’s teacher, Evagrius of Pontus. He taught that any thought that tempts us toward sin falls into one of eight broader categories: lust, gluttony, avarice, anger, sadness, spiritual lethargy (acedia), vainglory and pride. This teaching eventually became the basis for the ‘Seven Capital Sins’ of later, secular spirituality.

Cassian is largely concerned with this ‘practical’ spirituality. Saint Benedict set up a ‘school of the Lord’s service’, in which one learns to order one’s life in harmony with gospel precepts through the disciplines of silence and listening, obedience and humility, especially in loving service of guests and the weaker brothers in community.

But for those who wish to go on to greater heights of doctrine, Saint Benedict recommends The Conferences. These contain teachings on personal prayer, especially what Cassian calls ‘fiery prayer’, on the spiritual meaning of the scriptures and liturgical seasons.

Reading is of central importance in monastic life and formation. Monks are well-known for having preserved many ancient works of literature, and not only by Christian authors.

Most of our surviving manuscripts of ancient classical works were hand-copied and thus preserved by monastic scribes. We invite you to browse the various links in this section to see our recommendations for your own reading and prayer.

The Rule of St. Benedict

In his famous book of Dialogues, St. Gregory the Great mentions that St. Benedict of Nursia composed a rule for monks “remarkable for its discretion and its clarity of language.”

In the early years of the monastic movement, many rules were composed in different languages for monks of different regions and climates. Eventually, the majority of monasteries in the West adopted the Rule of Saint Benedict. In some cases, the Carolingian rulers (8th and 9th centuries) mandated the use of the Rule, but in other cases, communities simply chose the Rule because of its great spiritual wisdom.

Benedict’s Rule is renowned for its humanity and flexibility. The abbot should strive to arrange things so that “the strong have something to yearn for and the weak nothing to run from [RB 64: 19].”

The arrangements of Psalms for the daily celebration of the Office is still used today, and was even the basis of the Roman Rite until Vatican II. Nevertheless, Benedict himself is content to encourage communities to arrange the Psalms differently if there is a better way [18: 22].

The abbot has full authority yet must adapt himself to the characters of each monk. He should “study more to be loved than feared.”

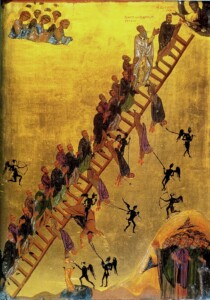

The center of the Rule is the Ladder of Humility, found in Chapter 7. Like similar ladders proposed by St. John Cassian and St. John Climacus, it gives us concrete indications of spiritual progress, while emphasizing that in Christian living, we paradoxically progress by humbling ourselves.

The Rule is written for cenobites, that is, monks who live in communities. Benedict has profound respect for hermits but cautions beginners to learn first in the crucible of community living how to engage in spiritual battle before going out the single combat of the desert.

Saint Benedict borrowed much of his text from an earlier rule, known today as the Rule of the Master (RM). Scholarship of the past century has learned quite a bit about Benedict’s personality from identifying the changes he made to RM.

Benedict recognizes that the abbot and his advisors must be given a certain freedom to address the differing situations in the changing milieu of the Church.

While the deep wisdom of the Rule is not always obvious at a first or second reading, since the eleventh century, it has been found to contain insights conducive to a stronger living of the Gospel even for persons outside of the cloister.

Benedictine Oblates study the Rule and aim to live in the world according to the principles of Benedict’s vision: robust community, dignified manual labor, daily prayer and reading, balance between work, study and prayer, humility, silence, and good zeal.

Creating a Community of Faith and Support

So, what is it like to be a monk? It can be a bit overwhelming at first if someone is not used to a strict schedule like ours. Even after many years, it can take real effort to get out of bed and sing joyfully.

Like everyone else, brothers go through periods where they are excited about prayer and times when they are not. But no matter how we feel, we go to the Divine Office!

Like everyone else, brothers go through periods where they are excited about prayer and times when they are not. But no matter how we feel, we go to the Divine Office!

This is a wonderful privilege and really helps the monk to get ‘outside of himself’ and to learn to turn over his own desires and feelings to God.

The other hidden part of this is community. We see the same brothers much of the time, every day. It is so very important to learn humility, to learn how to treat brothers in a way that is patient, supportive, and encouraging, and not picky, irritable, and so on.

Quite a bit of the ‘work’ we do involves the practice of loving the brothers. If we really give ourselves over to this, then God can really mold us into saints.