The Orthodox theologian John Behr has written that we live the faith going forward, but we understand it looking backward, as we see the mysterious working out of God’s grace in our lives and in the Church.

I thought of this in pondering the meaning of my recent election as Prior of the community. You read that correctly, by the way: we had an election on February 3 as the last step in our long process of obtaining full autonomy. We hadn’t wanted to publicize the election ahead of time because explaining the need for this is not straightforward, and we hadn’t wanted to cause any undue alarm. Perhaps that was an excess of caution. On the other side, it seems important to explain, for the benefit of our friends and others, the significance of the election.

Christ in the Desert, near Abiquiu, NM. Our association was always mutually enriching–the desert and the city!

As I’ve already indicated, this was necessitated by a “process” put in place to grant us full autonomy. That any process was necessary is already an indication that our situation was unusual. The Constitutions of our congregation give guidance for the normal route to autonomy of a newly founded monastery. Typically, a large house sends a group of 6-12 monks to a new location. This new house remains intially dependent on the motherhouse for resources of all kinds: members, money, and so on. After a certain amount of time, the new house stabilizes, starts to recruit its own new members, and gains the means to support itself financially. At this point, there is a canonical separation of the daughterhouse from the motherhouse, and the new house becomes autonomous. Autonomy is very important in Benedictine life: we are not, strictly speaking, a religious order, but a confederation of autonomous houses. This reality protects our vow of stability and its implications (we can’t be moved from monastery to monastery, and so we remain rooted in a particular culture). It also protects the notion that Benedict lays down, that a monastery is an image of Christ and His disciples: it is a group of monks gathered around a teacher and father (“Abba”=abbot).

Our road to autonomy was quite unusual. We were not formed by a motherhouse. Rather, three former missionaries began to live the monastic life, then went about looking for an abbey to adopt them. The monastery of Christ in the Desert responded to our request, and here is a place to express my profound gratitude to their community especially to the recently-retired Abbot Philip Lawrence, whose generosity and creativity have allowed many new houses to become part of the Christ in the Desert family. We were, in fact, one of four foundations or adopted houses, along with Nuestra Señora de la Soledad, near San Miguel de Allende in south-central Mexico, Santa María y Todos Los Santos near Teo Celo in southeast Mexico, and Thien Tam (Vietnamese for Sacred Heart) in northern Texas. About ten years ago, this situation began to pose certain problems. There were more monks canonically a part of Christ in the Desert living in the dependent houses than there were at the motherhouse. In fact, there were so many of us, we couldn’t feasibly have a meeting together because of the limitations of the desert.

At that time, in 2011, we were considered the strongest of the daughterhouses, but we lacked the canonical number of monks needed to be autonomous (normally eight, with exceptions given for six or seven; we had five in solemn vows). At a series of meetings at the provincial level, our Abbot Visitor, Anselm Atkinson, and his council worked out a special statute that would allow us to be autonomous, but with limitations and oversight given to the Visitor (who is the juridical head of the dozen or so houses of our English Province, but whose authority is limited to triannual visitations and more or less emergency situations). This meant that I was not elected by the brothers, but appointed by the Abbot President (the head of our congregation, which is divided into eight provinces, with a Visitor at the head of each province), after consultation with the community. Any such statute requires the approval of the Holy See, which we obtained at the end of 2011.

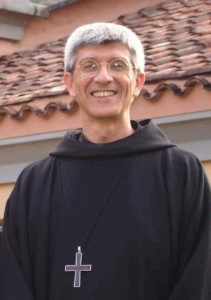

Abbot President Bruno Marin, who appointed Father Peter as the first superior of the autonomous monastery.

Now at that point, I had already been prior for seven years; I was appointed first by Abbot Philip as the prior of a dependent house, and I served at his bidding. He was the canonical superior, though he was always quite gracious in giving us a lot of freedom to propose our own way forward. This freedom helped prepare us for autonomy. When we became autonomous by the special statute, we were authorized to make our own decisions, with a few exceptions. One of those exceptions was that we could not elect our own superior until we had the full number of eight monks. When we reached this number, the statute stipulated that I had to resign so that we could elect a superior on our own. The Visitor and President agreed that they would accept my resignation only when the election began. This is a common occurence with bishops, who must, by Canon Law, submit resignations to the pope when they reach the age of 75, though the pope is under no obligation to accept these resignations immediately. Often, the Holy Father will do so only when he has a replacement ready to go, so that the diocese does not go for too long without a bishop. So it was in our case.

For a couple of days while we waited for the election to be confirmed by the Abbot President (thank God for email!), Father Brendan was acting superior. It was the first time in fourteen years that I was back in the ranks. I enjoyed it! But I was (re-)installed on February 5, and I’ve been happily back in action ever since.

Current Abbot President Guillermo Arboleda Tamayo, who was in Viet Nam when he got news of our election. He was able to confirm the election by his contact with our congregation’s curia via email.

I began by talking about the way in which we understand our faith in retrospect. The experience of our first-ever election was another opportunity to look back at how unlikely our survival and growth have been. The 70’s and 80’s were decades of great experimentation in religious life, and many, many new communities cropped up. Very few survived. That we have not only survived, but have continued to be confirmed in the path that God has opened up is a great sign of God’s will slowly unfolding in our particular project. Our growth has been deliberate and steady, allowing us to reflect quietly on the sources of monastic life and spirituality in a way that might not have been possible had there been a great swell of enthusiam earlier on. Who know what the future holds for us and the many friends we’ve made along the way, but we can go forward in confidence, in faith, seeing how Christ has led us through each stage so far.