When I was appointed prior of our community in 2004, one of my tasks was to work out realistic plan to build a genuine monastery cloister. We have been living in a former parish rectory and convent for twenty-four years. Most of that time, the space has been quite adequate. But as we have increased in number to ten, the need for better living quarters has become much more apparent. That said, the plan needed to be conceived from a long-range vantage point. The cost of construction is not trifling, and we are still a young community. Renovation and construction are psychologically straining, and we need to prepare ourselves well for this kind of work.

The magnificent choir of Westminster Abbey. Nothing quite so impressive for us! But one sees the architectural significance of the choir in a monastic church.

Thus, it seemed to me from early on that the first priority was the renovation of the church building. Take care of God’s house and let him take care of our house! The church is a public space, the place where most people learn about who we are. Now the structure of our church was conceived for the needs of a medium-sized parish, rather than for a small monastery. While we have been able to use the building profitably, we have long been aware of the ways in which the church’s architecture nudges us away from our professed goal of being a cloistered, contemplative community.

Renovation began in earnest two years ago when we commissioned our iconostasis and began work on the altar. The most important step, however, was certainly going to be the construction of a real monastic choir. Monks can spend over three hours a day in choir, and having a choir that meets the demands of the full Benedictine office would not only be a plus for us, but would also help visitors grasp that this is not a parish anymore, that it fulfills a different ecclesial function.

So we began the discussion of building a new choir. What would be our requirements for this improvement?

We have a beautiful neo-gothic church. The new choir must be appropriate to the space, with a design that doesn’t conflict with the gothic motifs that we already have. We were fortunate to discover New Holland Church Furniture in Pennsylvania, who have designed an absolutely beautiful and noble, yet functional, choir. It fits perfectly in the transept.

Our old choir had nineteen stalls, enough for our daily liturgy, but not enough when we hosted meetings, or when we invited Schola Laudis to join us for Solemn Vespers. The new choir has thirty-two stalls, adequate for both of these recurring needs.

We needed some sense of separation from the rest of the nave, without giving the impression of being distant or unwelcoming. Some brothers were even interested in a grille or rood screen. Ultimately we decided that this was too much separation. We decided on a low wall for the choir, and two additional low walls separating the choir from the nave. These look like small portions of a communion rail, though they are really stylized versions of a rood screen.

I mentioned in the previous post that our work on the altar and iconostasis, as well as our custom of celebrating Mass ad orientem could cause a kind of theological imbalance, implying God’s distance and undermining a sense of His welcoming immanence. Our design of the choir needed to address this.

Traditionally, the choir is part of the sanctuary. This means that in some monastic churches, for example, most Trappist churches, the sanctuary can end up stretching out over nearly the entire church. We had not capitalized on the possibilities of using the full, extended sanctuary to “close the gap” between clergy and laity. Again, the old parish architecture tended to form our imaginations in such a way so that we thought of the old, narrower sanctuary (all the way to the eastern apse, on the other side of the choir) as the sanctuary proper and the choir as something else. And the choir tended to act as something of a barrier between the laity and the distant sanctuary.

Then one of the brothers got a splendid idea. To express it best, let me quote from the General Instruction of the Roman Missal.

The Chair for the Priest Celebrant and Other Seats

310. The chair of the priest celebrant must signify his office of presiding over the gathering and of directing the prayer. Thus the best place for the chair is in a position facing the people at the head of the sanctuary, unless the design of the building or other circumstances impede this: for example, if the great distance would interfere with communication between the priest and the gathered assembly, or if the tabernacle is in the center behind the altar…[emphasis added].

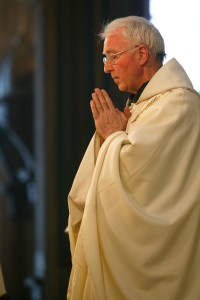

With our new, rather massive choir in the center of the church, putting the presider’s chair in the old sanctuary up near the altar would definitely interfere with communication between the priest and the assembly. So we put the presider’s chair on the west side of the transept, between the choir and assembly, where the priest will sit during the Liturgy of the Word. For the Liturgy of the Eucharist, the priest will make the long walk through the choir, up the old sanctuary steps, up the new predella steps, to the new altar and icon.

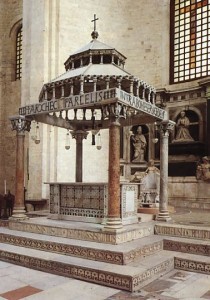

The altar of St. Nicholas’s Basilica in Bari, Italy. Note the three steps. This graded platform is known as the predella.

I describe this movement of the priest quite deliberately. Another strategy we have used for bridging the gap between the lay faithful and the monks is the copious use of processions. For example, when we process from the entrance of the church, through the nave, to the choir, part of what is expressed is our being called forth from the gathered assembly to our particular place in the church as monks. We go forth, as it were, to lead our lay brothers and sisters rather than slipping in from the sacristy and departing without having any ‘communication’ (and I intend this word in its full theological sense) with other members of the Body of Christ.

Most radically, this unusual placement of the presider’s chair helps to illustrate what I take to be the meaning of facing east. Now, when we turn to the East for the Kyrie and Gloria, as has been our custom, the monks will have their backs to the priest! We actually tried this out last Sunday, when the old choir stalls had already been removed and we were making do with wire chairs. The meaning was quite clear. We were all turning to face a common direction, and there was nothing particularly ‘clerical’ about the priest’s orientation, since he was very much in the middle of everything rather than far away.

The construction is finishing up today. We will have many photos available soon, and hopefully these will include photos of the actual liturgy in progress. We welcome any questions or comments!