“For what person knows a man’s thoughts except the spirit of the man which is in him?” [1 Corinthians 2: 11]

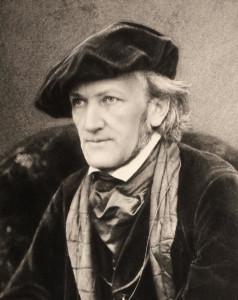

When Beethoven was a young man, one of his principal patrons, Count Waldstein, predicted that he would inherit the spirit of Mozart. Music historians will often make statements to the effect that the first half of the nineteenth century in Europe was dominated by the spirit of Beethoven himself, and that the second half was strongly informed by the spirit of Wagner. The negative expression of this latter reality belongs to the iconoclastic composer Claude Debussy, who said that his task was the exorcism of the “ghost of old Klingsor, alias Richard Wagner.”

Beethoven’s spirit is often connected to the rise in democratic movements following the French Revolution. He famously erased Napoleon’s name from the manuscript of the Eroica symphony when he heard that Napoleon had crowned himself as emperor.

To what does all of this refer? Two aspects come to light. The music of Mozart, Beethoven, and Wagner was experienced by many of their near-contemporaries (and many of us today) as touching on something profoundly true and beautiful. The crystalline perfection of Mozart’s symphonies and the heroic pulses of Beethoven’s symphonies inspired (in-spirited!) many young composers to take up the quill and try their own hand at composing. Musical composition is always a process of interior listening, testing to see how musical ideas imply other musical ideas, and how these in turn touch ineffably on the meaning of the human and divine. When one is immersed in the music of a Mozart, one learns from him how to listen and how to discern the true from the false, the profound from the trivial.

The first practical effect of this discernment is that early Beethoven sounds very much like Mozart’s music. Wagner’s earliest compositions sound eerily similar to Beethoven’s middle and late periods. Notice that Wagner’s music would almost never be mistaken for Mozart’s though. Something has changed with the appearance of Beethoven. This fact points us to the second important idea of the “spirit” of a man. However much Beethoven inherited Mozart’s spirit, as this spirit entered into another unique individual, Beethoven’s own creativity was quickened into life, an unrepeatable life. Thus emerged Beethoven’s own spirit that he bequeathed to the varying compositions of Schubert, Schumann, Liszt, Brahms, and Wagner.

“God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us.” [Romans 5: 5]

Wagner’s spirit led him to reconnect with a heroic past in mythology, a similar intuition to that of J.R.R. Tolkien in a later generation.

All the baptized partake of an analogous reality. But instead of inheriting the spirit of a fellow creature, we have received the Spirit of Christ, the Son of God. This is a true inheritance: “all who are led by the Spirit of God are sons of God.” Being led by the Spirit does not mean in any way that we become marionettes, any more than Wagner robotically reproduced Beethoven’s music. The Spirit quickens what is latent in us, and we develop into ourselves. This is why Scripture speaks of the Spirit as both our inheritance, and a pledge of a future inheritance into which we have yet to enter. “[You] were sealed with the guarantee of our inheritance until we acquire possession of it.” [Ephesians 1: 13-14] Led by the Spirit, we are already God’s children and yet something still greater awaits: “Beloved, we are God’s children now; it does not yet appear what we shall be.” [1 John 3: 2]

Just as a composer infused with the spirit of Beethoven learns from studying the master’s work, we will grow in the Holy Spirit to the extent that we accompany Jesus Christ in our daily lives, make Him our model and learn from Him how to discern the true from the false. We do this by participation in His mysteries in the liturgy, by meditating on Holy Scripture, and by recognizing Christ’s presence in His Body the Church. Many of us resist this with a false understanding of what it means to take responsibility for our own lives. Critics of religion will claim that the Church’s morality deadens our individuality, infantilizes us by scripting our own lives for us. But as my examples of composers demonstrate, the spirit of Mozart did the opposite for Beethoven. It freed Beethoven to develop into the great light for so many who came after him. If this is so with the spirit of a man, how much more will the Spirit of the Creator God free us to mature into true individuals, as articulated members of Christ’s Body? As C.S. Lewis well expressed the freedom of those led by the Spirit, “How monotonously alike all the great tyrants and conquerors have been: how gloriously different are the saints.”

Come Holy Spirit!

Prior Peter Funk

Pentecost, A.D. 2021