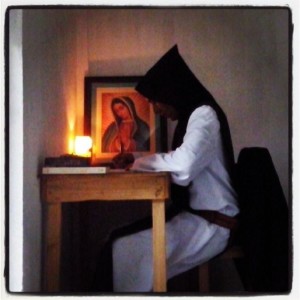

Shortly after I entered the Monastery, a man approached me after Mass one day. He invited me to join him to sit in protest, praying outside an abortion clinic. Since I was not allowed to leave the cloister without permission, I explained to him that I was not able to join him, but that I would pray for him. He was clearly disappointed. I suspect that he thought I was offering an excuse and simply didn’t care to go.

Episodes like this raise the entire question of the efficacy of prayer. One commonly sees Christians called out in the media for offering “thoughts and prayers” at a time of tragedy. Indeed, it’s painless to post such sentiments on social media, and so it’s perhaps good that Christians are challenged to demonstrate meaningful actions that back up such words. Offering “thoughts” really does open one to criticism. My thoughts accomplish little as long as they remain inside my head.

Prayer, on the other hand, always involves an Other—God. The truth is that prayer is an action. Praying well, with real faith and devotion, is not always easy. By inviting God into a situation, we bring the potential of new types of insights. And these, in turn, can lead to new types of actions.