Think about all of the things you know, not by experience, but by testimony. Virtually everything we know about history, for example, we know because others have written down descriptions of past events. I had an art teacher who liked to say that if we learned everything from experience, most of us would die from poison mushrooms. How do we know that some mushrooms are poisonous? Because someone told us, and we trusted them.

Here’s a more troubling example: what we know about current events is from the reports of anchormen and journalists. This raises an important point. The knowledge that we have from testimony is only as good as the trustworthiness of the source. When assessing someone’s testimony, we check carefully to see whether that person is reliable. In other words, the character of the person testifying is important.

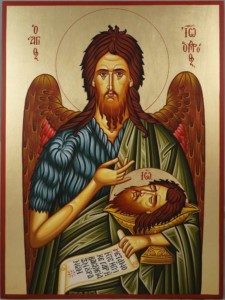

John the Baptist is one of the most important persons in the New Testament precisely because he bears testimony to Christ as the Messiah. And what we discover, when we look more closely at John’s career, is that he was widely known to be trustworthy. His character was unassailable. He spent a lifetime meditating on the Scriptures and living a manifestly holy life. People of all kinds were fascinated by him. Roman soldiers went out to hear him speak and ask his advice. Herod’s career was jeopardized by John’s public criticism. The historian Josephus tells us that John’s arrest happened because Herod feared that John’s popularity could lead to an uprising.

John insisted on personal integrity and drew to himself bands of disciples. And he did this not for personal gain, but for the sake of God’s kingdom—this detachment was part of his integrity. This meant that when the Lamb of God appeared, John was ready to point to Him and to send his own disciples to follow Jesus. These disciples included Saint Andrew, the brother of Simon Peter.

John thus prepared a people ready to receive Christ, and He testifies to Christ so that others can see and follow. In this, John provides an important example for us.

In his years in the wilderness, meditating on God’s prophecies, John learns, under the teaching of the Holy Spirit, how to live an upright life in the truth, and how to recognize the signs of Christ’s coming and His presence.

In our world, many people have forgotten about Jesus Christ and His message of redemption, forgiveness, and the promise of eternal life. When we lament this reality, often our first response is to think about organizing some kind of movement or program, or joining such a movement. But the start of any renewal, as we see in monastic history, time and again, is first to check our own reliability as witnesses. Christ hasn’t gone anywhere—but do we see Him in His daily coming? Do we see Him in our neighbor, in the guest, in the poor, in the superior of the monastery? If we don’t, perhaps we can ask John to point to Him. What John tells us is that we can prepare ourselves for Christ’s daily advent by withdrawing into the desert of our hearts and there meditating on God’s prophecies, purifying our own hearts and clearing away distractions.

When it does come time to point others to Christ, how strong will I be as a witness? Am I truthful, disinterested? In a word, am I a reliable witness, a credible source of information? Or do I risk making the gospel less credible by my sins or imprudence? Perhaps John is exactly the saint we need today to prepare again a way of the Lord. Maybe we can leave behind the unreliable information we get from the media and go out to the wilderness where John will teach us again to see Christ passing by. We can learn to say with John, “Christ must increase, and I must decrease.”

One last important example of John’s witness is that John tells us that he rejoices when he sees Christ as the friend of the bridegroom rejoices to see the groom receive his bride. This narrow path of self-denial and witness to Christ will eventually be a path of joy. It will make us fearless witnesses after the pattern of John the forerunner and herald of salvation. Blessed are we to celebrate the life of this great man today!