The month of February, despite its brevity, is full of critical liturgical celebrations. I use the word “critical” in a precise sense: “of, relating to, or being a turning point…” according to Webster’s. These turning points were somewhat more transparent in the old calendar, before the invention of “Ordinary Time.”

I invite you to consider the feast of the Presentation (or, as it is often traditionally called, “Candlemas”), which we just celebrated this past Tuesday. This celebration falls forty days after Christmas and is rich in symbolic associations. It is the Incarnate Word’s first visit to the temple—his temple. In the hymn at Lauds on February 2, we sang,

“Parentes Christum deferent,

in templo templum offerunt.”

”His parents carry the Christ;

in the temple, they offer the [true] Temple.

Aside from the obvious paradox in this poetic line, there is a quiet allusion to Christ’s Passion. Christ is brought to the temple as an offering, to be redeemed on the same mount where Abraham had nearly sacrificed Isaac to God. Not only that, but in referring to Christ as the Temple, the hymnist surely is reminding us of a different exchange. The new Temple of Christ’s Body is inaugurated and revealed through His death and resurrection [cf. John 2: 19-22].

The Magnificat antiphon at Vespers this evening (taken from the Benedictine lectionary for the office of Vigils) once again uses the word temple, but in yet a different sense. Here is the text in full, from 1 Corinthians 3: 16-17:

Do you not know that you are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in you? If any one destroys God’s temple, God will destroy him. For God’s temple is holy, and that temple you are.

According to the traditional four senses of Scripture, Herod’s temple is the “literal” temple, and Christ’s body is the temple in the “allegorical” or Christological sense. In this quotation, Saint Paul shows us the “tropological” or moral sense. “You are the temple of God! And the Holy Spirit dwells in you!” Thus, the procession on Candlemas, accompanying Christ to the temple, is, in a sense, a procession inward, to the temple that we are. We carry lighted candles, the illumination of the Holy Spirit, into our hearts where Christ wishes to abide.

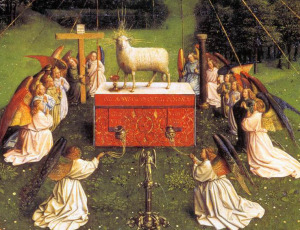

Again, the beauty of this theological reality is accompanied by a serious challenge for us: that we strive to be more and more faithful to our baptismal vows. After all, in our baptisms, we died to ourselves, and we were conformed to Christ’s own Passion, that we might also be conformed to His Resurrection. If we are, with Christ, the temple of God, then we are also an offering to God. Let us, then, today, rededicate ourselves, to “present [our] bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God [Romans 12: 1].” In making this effort, we will undoubtedly discover various resistances to this spiritual renewal, and this in turn will help us to craft a realistic and effective ascetical plan for Lent, only eleven days away.

The world needs spiritual pioneers more than ever. Let us accept God’s invitation and join the saints’ procession to the final temple (the “anagogical” temple), the Church Triumphant in heaven.