Why a blog on a monastery website? It could be used to share monastic spirituality, and I do hope to cover that. The seniors in our community teach monastic spirituality to the novices and juniors regularly. Thus, not only our own experience of prayer, work and silence should offer some fresh insights on Christian discipleship, but we should also be somewhat experienced in teaching this perspective to others.

What I have discovered, however, is that the spirit of monasticism can be misunderstood, or appropriated for ends not entirely consonant with the larger aims of the monastic or Christian life. For example, I’ve noted that novices with energy and good will become easily discouraged, or seem not to know what it actually meant by key terms like faith, hope, repentance, even prayer. So I’ve asked myself, and I’ve asked the other seniors, especially Fr. Brendan our novice master: what are we up against, exactly? It was not the case that the men entering were not called. Rather, something in their upbringing caused them to have difficulty translating what we were saying and doing into their own understanding.

I also experienced tensions in myself. I mentioned in the previous post that I am a proponent of reading Scripture in the spiritual and allegorical sense. I have arrived at this gradually, beginning when I studied for my Master’s degree in Scripture. In those days, I loved all of the historical-critical stuff. I even wrote an article for This Rock magazine defending scientific methods of exegesis in Catholic faith (amusing aside: my editor glossed a reference I made to Fr. Raymond Brown, calling him ‘controversial’, in spite of his having been named by two different popes to the Pontifical Biblical Commission; I refused to go on record saying that about him, so I dropped the reference).

Fr. Raymond Brown, who did Catholics the great service of showing how Catholic doctrine was not contradicted by scientific studies of the Bible

But then I had to teach Psalms and other courses on Scripture to our novices. And I realized that what they needed was how to understand the allegorical readings. But I wasn’t sure that I understood them! So this called for some conversion on my part, too.

So this blog is an exploration of how we have tried to work through these tensions, and what we have found in doing so. We have been helped immensely by the insights of a number of contemporary thinkers, and I will be introducing you to them over the coming weeks. I’ve already mentioned Jean LeClercq. The three thinkers who have provided the most help in sorting through what sort of dilemma we are facing I will deal with right away. They are Alasdair MacIntyre, Mary Douglas, and Henri de Lubac. It is important to stress that they have not necessarily offered ‘answers’, but demonstrated, in strikingly correlative ways, what sort of questions faithful Catholics ought to be asking in our confusing contemporary situation. As we will see, MacIntyre demonstrates that even understanding our first principles requires that we grasp the ‘first questions’, that even first principles are uncovered by argument. Let’s use LeClercq’s book as an illustration. Monks seek the Kingdom of God, according

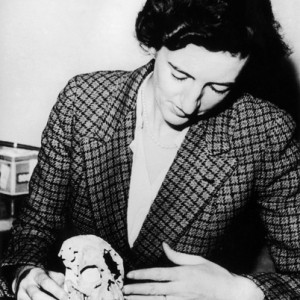

Mary Douglas has provided more than her fair share of ‘ah-hah’ moments.

“Just in our lifetime our society has become looser and more private, it becomes extremely difficult to hold to any permanent commitment whatever, least of all to organized religion.”

to St. John Cassian. But what does that look like, and how do we get there? And more importantly, LeClercq forces monks to ask this key question, “Is our method of study consonant with this goal, as commonly conceived by monks?” When he wrote, the answer was, “No.” Vatican II’s Perfectae Caritatis invited all religious to a rediscovery of the spirit of their founders and traditions. LeClercq’s work was vindicated as monasteries dropped scholastic and Ignatian methods of formation and returned to the Desert Fathers and medieval Cistercians. And a new immersion in these texts raised questions about how we understood the Kingdom of God, and how we might have been misunderstanding it when our tradition had been distorted.

Alas, all three authors can be quite difficult. I see it as part of my mission, too, then, to help introduce some of their key insights in the ways we have made sense of them in our monastery. We actually have come to use geeky-sounding terms like “restricted code” as a way of reminding ourselves of the importance of silence and symbolic communication in a monastery. Mary Douglas contrasted “restricted code” with “elaborated code,” the language form of modern college graduates and market economy, the language of constant chatter, negotiation, and justification. Monks should only rarely communicate in this way. Restricted code is about reinforcing communal roles and structure through symbolic behaviors like seating arrangements, standing when the abbot enters the room, kneeling when the Blessed Sacrament is exposed. This is to say that Mary Douglas has given those of us who have college degrees (which is most of us) a warrant for conversion that engages the rational part of the person as well as his faith. Because fideism turns out to be one of those hidden problems that we need to name.

But aside from the Church Fathers, no one has assisted my own puzzling through these problems like MacIntyre. So to him we turn next.