Key concept #2: Traditions are arguments before they are agreements. And then they are arguments after they are agreements.

(h/t to Adrian Belew)

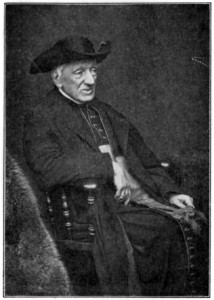

This appears to me as one of Alasdair MacIntyre’s most important insights. He borrowed the idea from Blessed Cardinal Newman, and he refined it considerably.

Why is this important? For several reasons, though I will mention two today.

In my previous post, I said that liturgy is ‘first theology‘. A fine sounding notion! But what do we find when we gaze out upon the liturgical scene in the contemporary Church? Lots of disagreement. In fact, you will hear Catholics say that we’ve been fighting over the liturgy for forty years or more. And this liturgical stew only got messier when Pope Benedict XVI gave priests permission for a wider use of the ‘extraordinary form’ of the Mass. So what, exactly is the material of the liturgy at this point, the material that is supposedly going to give form to prima theologia?

I would not argue that our present situation is ideal. But I also don’t believe that the situation in, say, 1950 was ideal, either, but for the opposite reason. Church tradition had come to be seen as something unchanging and unquestioned. Now, by contrast, it has come to appear as something up for grabs. The reality is something else. Tradition is an argument. And it is an agreement on what to argue about and how to argue. It is not true that tradition-as-argument means ‘anything goes’. It may appear that way in an emotivist society, such as ours is, where arguments are not rational but are exercises in emotional manipulation.

This brings me to the second point. The idea that traditions are arguments makes it possible for them to be rational. MacIntyre generally shows great respect for other thinkers, even when he strongly disagrees with them. This makes his open criticism of Edmund Burke more piquant. Why is Edmund Burke in his sights?

During and after the French Revolution, Burke began to write down his intellectual defense of Tradition. Few people are aware of just how radical many elements of the Revolution were. There were movements to change the names of the days of the week and the months of the year. There were proposals to renumber the years, using a starting point other than the birth of Christ. There were proposals to change the length of the week and the month, to remove them from the lunar associations. Why? The supposed goal was to organize society in a more rational manner. A month of 30 days or so may or may not prove functionally most effective for human organization, or so the theory went. So maybe ten months of 36 days would make more sense. Maybe eight days of work and two days off…It was all slightly crazy, though it must be stressed that this was done in the name of reason.

So what did Burke do? Did he give a defense of the rationality of tradition in the face of these assaults? Not really. In fact, in his writings he comes close to celebrating tradition precisely as irrational. And this thinking has infected us ever since. Why genuflect when you come into Church? Because the Tradition says so! And don’t ask any more questions! Why did the old Ember Days have seven readings on Saturday? Who knows? And who cares what reasons there might have been–we ‘traditionalists’ don’t need to ask these questions. [This is strongly akin to the same way in which ‘blind obedience’ came to be a religious virtue.] I’m exaggerating, but the point is, for a tradition to be rational requires something like what Newman and MacIntyre have taught us: there must be some way for those engaged in the tradition to give each other persuasive reasons for doing one thing rather than another.

As a young man, Newman discovered that the post-Apostolic Church shaped tradition by arguing about its development.

Where we stand with the liturgy today is, I believe, somewhere before the midpoint of what I hope will turn out to be a fruitful (though tumultuous, alas) reflection on the meaning of the liturgy. Consider the choice facing a pastor who wishes to celebrate the extraordinary form of the Mass: he could, of course, simply begin offering Mass in this way because he has personal feelings in favor. But more often, what happens is that he decides to do so for reasons: to educate his parishioners on the broader tradition of the liturgy; to foster a greater sense of devotion; and so on. Now, once he gives such reasons, and hopefully he does so either in some public parish forum or to his fellow clergy in the local deanery, he is open to being criticized for his choice and for his supporting reasons. He will have to make a defense of his reasoning, and he will have to appeal to shared agreements about the liturgy in order to persuade others. He may end up abandoning the project, or he may convince others to begin celebrating the extraordinary form. Or they may continue to disagree, but now the argument has become considerably more refined on both sides (we hope). Everyone has had to reflect together, and so have become more reflective and reasoned. And out of such exchanges, the Church as a whole will gradually come to have better and better reasons for clearer and clearer choices. As poor choices are weeded out and lame reasons are abandoned, the liturgy will come to be more recognizably consistent, and–very importantly–more ‘rational’ itself. But not ‘rational’ in the Enlightenment sense–I mean this in the sense that we are to offer to God “rational worship!”

“I appeal to you therefore, brethren, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual [Greek–logiken…logical!; Latin–rationabile…rational!] worship [Rom 12: 1].” This in turn will allow us to “be prepared to make a defense [lit. “to give a reason”; Gk–logon, Latin–rationem] to any one who calls you to account for the hope that is in you [1 Peter 3: 15].”

P.S. For those of you who don’t know who Adrian Belew is, he wrote and sang (? shouted?) the lyrics to this…song: