The concept of kingship, considered throughout history and in multiple cultural contexts, varies quite a bit. Contemporary Americans tend to equate kings with tyrannical figures wielding huge amounts of arbitrary governmental power, whether it be the power of taxation exercised unhappily by George III at the expense of the Colonies, or the power of complete policy control as brandished by the Sun King, Louis XIV (“I am the state,” “L’état, c’est moi,” was his memorable way of expressing it).

What is missing from this view is perhaps the most important historical aspect of kingship, one that gives unity to the institution as practiced by many different cultures. That aspect is the sacrality of the king. A king (or a queen, for that matter) is above the law and above the state not because he won the lottery for raw political power (though in each culture the institution historically almost always started out that way), but because the king represents the divine principle offering a common purpose to a diverse people. This common purpose brings with it a sense of transcendence and meaning to the life of the king’s subjects. To put it more plainly, Pharaoh was a god, and when the Roman Republic came to its crashing end with Caesar crossing the Rubicon, it was not long afterward that his adopted son Augustus moved to bestow deification on the deceased first Emperor.

The Exodus from Egypt was seen by the Israelites as a theomachy, a war of the gods, in which the mysterious desert-dwelling God of Moses vanquished Pharaoh. Eventually, through the insights of the great prophets, Israel came to the realization that kings were not gods at all. In fact, there was only one real God, the God of Abraham. This is a much more intellectually challenging proposition than we care to admit. Much of contemporary atheism is a nod toward this difficulty, even if it is dealt with by outright dismissal. That is to say a god out of sight is a god out of mind.

After the Exodus, Israel maintained what scholars call an “amphictyony,” a league of separate tribes under God, but as we see in the book of Judges, it was a highly unstable arrangement because the people tended to forget about this invisible God.

Things came to a crisis as the great prophet Samuel was aging. His sons were not up to the standard of the great judges, and the people called for a king. Samuel offers an impressive list of griefs that such a request would bring with it: military conscription, harems, taxes, et cetera [see 1 Samuel 8], but the people persisted, wishing to be “like all the nations.” God gave in, as it were, and before Samuel died he would anoint Saul king, abandon Saul, and then anoint David king. That wasn’t the end of it for poor Samuel, as the kingship continued to disturb even after death, when Saul, possessed by an evil spirit, had him summoned up by the Witch of Endor.

Now, in keeping with my theme, it is important here to note that the king is made king by anointing, just as Aaron was consecrated high priest by the anointing of the prophet Moses. As noted in different ways by prominent thinkers like René Girard, Ernst Kantorowicz, and Giorgio Agamben, from this perspective a king becomes a kind of non-person. Like the priest, he is likely to wear special clothing that marks him as sacred and conceals his individuality. A king, when killed, can be a stand-in for animal sacrifice. As with Julius Caesar, the king’s death can be the moment of apotheosis. A similar dynamic surrounds the figure of Oedipus after his exile and blinding.

David’s entrance into the history of Israel demonstrates this in an interesting way. When Samuel visits Jesse, he is presented with seven sons. God chooses none of them. The number seven is that of completion. In some sense, those are all of Jesse’s sons. The eighth, who turns out to be God’s chosen one, is an anomaly, out pasturing the sheep while the others are vying for the crown. David’s name is unusual, meaning simply “beloved,” “the dear one.” His name is cognate with the term of fondness used by the lovers in the Song of Songs. He is seemingly loved into being by God. He is a man after God’s own heart.

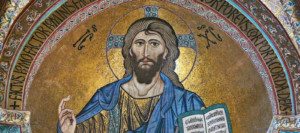

While David is often enough today depicted as a ruthless and scheming ruler, a run-of-the-mill king or chieftain, it is significant that God, Who sees the heart, made an everlasting covenant with him. If His people were going to have a king, God would do it the right way, one dynasty representing the one God. A descendent of David would sit on the throne forever, we are told in Psalm 88 (89). And indeed, the fulfillment of this prophecy would come about in the Resurrection and Ascension to God’s right hand of the Son of David “according to the flesh [Romans 1: 3–note that in all the disputes between Christ and the authorities, no one questions his legitimate descent from David].

More than that, in the pouring out of the Holy Spirit (i.e. the anointing) on Pentecost and the institution of the present sacrament age, Christ our King is with us at all times, if we learn to see by the Spirit, to walk by faith. Christ is in the Church, Christ is present in the Eucharist, He is the altar, the priest, the Easter candle, He is present in the poor, in the prisoner. Let me now return one last time to my opening point, that kingship is about more than government; it is about how to understand the sacrality of things. The crowning of Christ in the Ascension is the moment when the great and final transformation of all things begins, when the true purpose of all creation begins to be manifest. All things and all peoples are being united mysteriously under the King of Kings, under the rule of the Logos. In the words of Saint Benedict, we live in the time when the humblest tools of the monastery can be treated with the reverence normally reserved for vessels of the altar [see the Rule of Saint Benedict, Chapter 31], because they belong to and manifest the True King, He Who reigns forever and ever. Let us praise Him!

[This is an expanded version of the program notes from Solemn Vespers on Saturday, November 24.]