I’ve been trying to figure out what it is about George Weigel’s recent post “Catacomb Time?” doesn’t sit right with me. I suspect that it is first of all due to an accumulation of fuzzy complaints with someone-or-other not quite specified. Who inhabit those “Catholic circles” who have “a passion for writing Build-It-Yourself Catacomb manuals”? I honestly have no idea who is meant by this. I suppose that he is referring to the Benedict Option, for which there is no shortage of critics, despite the fact that no one seems to know what it is exactly. The reference to “lukewarm, pick-and-choose” Catholics is always a dangerous one. Who of us doesn’t fall into the “pick-and-choose” category from time to time, even often?

Then there is this larger quote, expressing what seems to me a common enough sentiment, but one I just can’t get behind personally:

This same judgment—Catholicism by osmosis is dead—and this same prescription—the Church must reclaim its missionary nature—are at the root of every living sector of the Catholic Church in the United States: parish, diocese, seminary, religious order, lay renewal movement, new Catholic association.

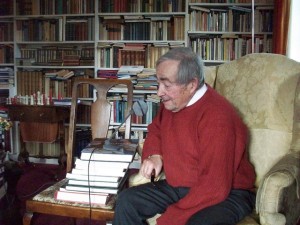

George Steiner in my dream study. He proposes “cortesia” (courtesy) as a mode of mutuality as a partial antidote to a critical and wordy discourse that empties language of its theological import. In this, he comes remarkably close to Benedictine “hospitality” as a mode of encounter, and perhaps a way to reinterpret “mission” away from the excessive freight of unidirectional conquest toward a humble acknowledgement of the potential contributions of potential converts.

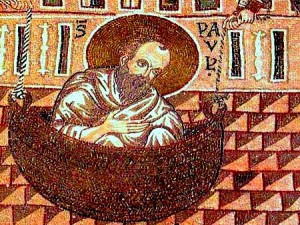

“Every living sector” of the Church in a country of almost 70 million Catholics? That’s a big claim. I think what troubles me most about this sort of language is the absence of any feint in the direction of the work of the Holy Spirit in animating the Church. Then there is the question of whether my own religious community qualifies as a “living sector” and whether we actually share that judgment and prescription. One reason I balk at that way of phrasing the “judgment” that “Catholicism by osmosis is dead,” is that it privileges what Mary Douglas refers to as “elaborated speech code” (the language of academia, personal commitment and conviction, related to what George Steiner calls out at the beginning of Real Presences) at the expense of “restricted speech code,” the more passive communicative modes of ritual and symbol. Much of what we learn in the Church is at least somewhat osmotic. Yes, we should pay attention at the liturgy, but often times it takes all kinds of exposure at various levels of awareness and engagement before connections are made. Perhaps I sense here, fairly or unfairly, a neglect of the fundamentally receptive nature of faith, prior to any genuine engagement in mission. St. Paul, the greatest missionary of all, spent well over a decade anonymously living the life of a Christian before the Holy Spirit set him apart as the Apostle of the Gentiles. During that time, what was he doing? Praying? Re-reading the Scriptures? I don’t know, but it was certainly a life of withdrawal, maybe not to the catacombs, but a withdrawal nonetheless.

And then let us not forget who is the patroness of the Church’s missions.

St. Therese, patroness of the missions. Behind the Church’s missionary activity is St. Therese’s hidden little way of complete faith in all things.

I will leave it to reader to think about the connections between the contemplative life and missionary effectiveness.

Let me end with a little more explanation from Mary Douglas. In the first chapter of Natural Symbols, she relates asking her progressive clerical friends (in 1970) why they think it’s a good idea to move away from the Friday abstinence to more personally meaningful acts of charity–like working in a soup kitchen on Friday.

I am answered by a Teilhardist evolutionism which assumes that a rational, verbally explicit, personal commitment to God is self-evidently more evolved and better than its alleged contrary, formal, ritualistic conformity.

I will admit to nitpicking here a bit, but I think that it is worth watching our language very carefully on these points, lest we saw off the branch upon which we sit. The overall tone of the article supports an individualistic and activist mode of Church life that has the potential to undermine the communal, receptive, gratuitous, gracious, and humble life of faith and hope. Surely one of the points of the young Josef Ratzinger’s “Future Church” article is precisely that we are being called away from “edifices…built in prosperity,” as part of an invitation to leave behind triumphalism. Weigel comes uncomfortably close to a triumphalism-minus-edifices. It is striking that after the long quote from the future pope, a quote that ends with an emphasis on “faith in the triune God, in Jesus Christ, the son of God made man, in the presence of the Spirit until the end of the world,” Weigel never again mentions faith, Jesus Christ, or even God. Again, I will admit that finding such lacunae in a blog post runs the risk of straining justice. But as a monk, I am inclined to be watchful on these counts.

More than anything, this serves as an introduction to Mary Douglas, whose work I have put off writing about for long enough…

UPDATE: Recall that the relationship between mission and contemplative life is the crux at which our community began. Also, that while it is hard not to agree that practicing one’s faith will require great resolve and strength in the coming years, maybe decades, this must be a practice rooted in repentance and joyful humility, grounded in the sacrifice of Calvary, celebrated daily in the liturgy. Finally, while Fr. Ratzinger did say that the future Church will make “bigger demands on the initiative of her individual members,” [emphasis added] this mention of individual members needs to be read in the context of the future pope’s voluminous writings on the liturgy and the Church. The initiative he is calling for surely must be greater fidelity to the reality of the ongoing Incarnation in the local church (including a high mystical “Ignatian” vision of the bishop as Christ and priests as the bishops’ vicars). Otherwise, Weigel might be heard to be inviting individuals to greater creativity, initiative in a maverick kind of sense, rather than in a sense of responsive answerability toward the gospel. And the first step may well be admitting that I’m part of the problem with the contemporary Church.

![Christ's Ascension is the founding movement of every liturgical celebration. Now He intercedes for us at the right hand of the Father [Romans 8: 34].](https://chicagomonk.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/ascension-coptic-215x300.jpg)

![Did you see some kid fall from the sky? Nah. [Bruegel the Elder's depiction of Icarus unmourned]--"Not an important failure," as told by Auden.](https://chicagomonk.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/icarus.jpg)