We have arrived again at the holiest time of the Church’s Year, the annual celebration of the Paschal Mystery, our Lord’s Passover. It’s hard for me to believe that this will be my 27th Triduum at the monastery. The liturgy for this holy time can be bewildering when we first encounter it, but also exhilarating–and for the same reason. Everything is new, slightly disorienting. Time is suspended. Melodies and rituals suddenly appear that remind us of our first childhood memories of Easter.

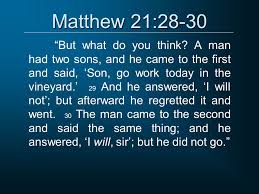

Over time—and this is especially true for monks who must study the liturgy and practice it regularly—the ceremonies become more familiar, even if they remain special to this time of year. For some of us, there is a temptation to a bit of boredom—the old feelings no longer emerge with the same intensity. Every Triduum features a liturgical blunder or two–sometimes the same one many years running, and this can tempt us to cynicism. But these temptations should be dealt with in the same way that we deal with every temptation: with resistance. When we begin to understand the liturgy, not as a prompt for good and edifying feelings, appropriate as these might be, but as central to our permanent identity as children of God, we can transition into a deep sense of belonging to Jesus Christ and His Church. This identification and belonging will remain with us and inform the rest of our lives as Catholics throughout the year.

Once again, this applies especially to monks and nuns, who have espoused themselves to Christ. The transition of which I am speaking is analogous to one that we see in certain married couples. They begin their lives together with excitement, expectation, even a kind of infatuation with each other, and the joy of having been loved and accepted. There are new experiences of owning a home, of pregnancy, childbirth, school, in-laws, new family rituals at Christmas, and so on and so forth. This gives way eventually to routines, and as the new and exciting becomes the familiar and dull, there is a risk of each spouse focusing on the small annoyances of any relationship with inherently limited and even flawed persons. There are heartaches with children who suffer health problems, disappointments with careers and there are compromises. The temptation is to boredom and even a sense of resentment. But if this temptation is resisted, what emerges is the beauty of belonging to one’s spouse, of totally identifying with that person with whom I have made a lasting covenant, and struggled to live those vows in fidelity. These are the couples who can sit together for long periods of silence, simply content to be with their “better half,” appreciating the presence of the long-beloved.

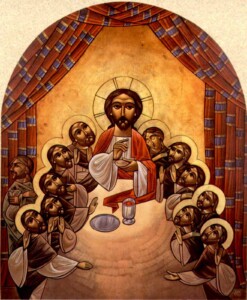

The Holy Triduum is like the Church’s wedding anniversary, the annual reminder that we have been espoused by the great Bridegroom Who laid down His life for us, Who poured out His Blood to cleanse us and make the Church a worthy Bride for Himself, spotless and beautiful. When this reality is newly embraced, it can move us to great torrents of emotion. It can so move us even after many years. But it can also carry us away to a different kind of experience, that of profound and peaceful contemplation, the silent adoration of the Holy Trinity, to Whom be glory and honor forever. Amen.