I didn’t much like the song “The Little Drummer Boy” when I was young, finding it a bit trite, even contrived. Then I heard this version.

That might be the best track off of the amazing 1966 “Noel” album that Baez recorded with, of all people, Peter Schickele, better known for his PDQ Bach hilarity. It was conceived as a protest against the Vietnam War. The collaboration was such a musical success that Baez and Schickele combined for two more recordings.

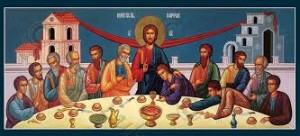

Why a Christmas album for peace? I haven’t come across any interviews where Baez explains this choice. She had been, and would continue to be, outspoken against all war. She wrote many songs protesting injustice, and she recorded many songs of other writers on related topics. She could have made virtually any of her albums into statements for peace. But she chose to sing about Jesus Christ. She could have written songs using the teaching of Gandhi, who was a strong influence on her decision to found the Institute for the Study of Non-Violence. But she sang about the Prince of Peace.

So sand the prophet Isaiah, in another time of great turmoil and distress, while Jerusalem was under threat by the powerful Assyrian empire:

For every boot that tramped in battle,

every cloak rolled in blood,

will be burned as fuel for fire.

For a child is born to us, a son is given to us;

upon his shoulder dominion rests.

They name him Wonder-Counselor, God-Hero,

Father-Forever, Prince of Peace.

His dominion is vast

and forever peaceful,

Upon David’s throne, and over his kingdom,

which he confirms and sustains

By judgment and justice,

both now and forever.

The zeal of the LORD of hosts will do this!

[Isaiah 9: 4-6]