We must become different kinds of persons.

The liturgy is the primary place where this happens. And this is why the liturgy first disorients in order to re-orient us as new kinds of persons.

What kind of persons are we to become?

If I may coin a term, we must become eschatological persons.

The eschaton is the end-time, the goal of history, the eternal life in communion with the Holy Trinity that we hope for. A person who is eschatological lives already with one foot in this reality.

Let me unpack a bit of this today.

Becoming a different kind of person really is a matter of kind and not degree. The aim is not to become better at some set of behaviors that we already possess, to be nicer, more generous or happier. Becoming a different kind of person involves receiving and cultivating capacities that my old self did not possess. Let me use music again as an analogy. At age seventeen, when I first heard the album Close to the Edge by the band Yes, I couldn’t make heads or tails of the music. As a result, I judged it inferior to the music I liked at the time, mostly variations on blue-eyed soul and the later New Wave bands of the mid-1980’s. The album was on one side of a cassette tape, and I liked the music on the other side. So rather than rewind, I began flipping the tape over and playing Close to the Edge without listening very closely (I used to listen while practicing basketball and while running). After a few such passive listenings, I suddenly realized that I was actually able to identify recurring themes, and I began to have a sense for how the very energetic opening section was constructed musically. After some months, I had a capacity that I did not have before, a capacity to understand this difficult kind of music. I wasn’t necessarily a better listener, or a more discriminating listener. Rather, my ears had changed, my mind and heart had changed. Close to the Edge became one of my favorite albums.

Now conversion to Christ is analogous, though stronger. In my example, one might argue that in fact, I already had the capacity to understand Close to the Edge, but it was latent and needed actualization, to use Aristotle’s term. By contrast, when we are initiated into the “things handed down to us,” the Christian faith, we really do become new creations. By grace, we receive a share in the divine nature. Therefore we receive potentialities and capacities that we did not have before baptism [it is perhaps important to note that all human beings have the capacity to receive this divine life; but the divine life is not present in the same intimate way before baptism].

What are these new capacities? We would normally group them under the three theological virtues of faith, hope and charity, and the gifts of the Holy Spirit: wisdom, understanding, counsel, knowledge, fortitude, piety, and fear of the Lord.

Here’s the trick, though. Since these virtues and gifts are proper to the divine nature and not our own, their exercise should, at first and perhaps for prolonged periods of time, feel unfamiliar, perhaps even strange and uncomfortable. We might not even recognize what it feels like to walk by faith, to act in charity or live in hope, even when this is actually happening, just as we aren’t usually aware of our breathing until we pay attention. We can become accustomed to the divine nature at work in us through self-denial (which reduces the distractions of the flesh to allow us more freedom in the Spirit), and through prayer. The work of asceticism and prayer is the work of owning this new self, making it who we really are.

The liturgy is the primary place where we are acclimated to the divine life. There we co-operate with our high priest and Head, Jesus Christ, to offer worship to the Father in the Spirit. We are immersed in the divine life, and it appears to us, as it were, through the senses. The visible, audible, and tactile signs of the liturgy really do communicate God’s loving, enveloping, and suffusing presence. The liturgy conforms and accustoms us to the divine nature, to the life of heaven, the eternal life to which we aspire, the celestial commonwealth that is our true abiding homeland.

But the liturgy will often feel unfamiliar, strange, perhaps even a bit irritating at times for the same reason that the divine life is at first unfamiliar. It is not ours; we didn’t invent it based on some already-existing human capacities that we discerned. The liturgy is a gift from God, attuned to and ordered for the human person, to be sure, but not of the human person.

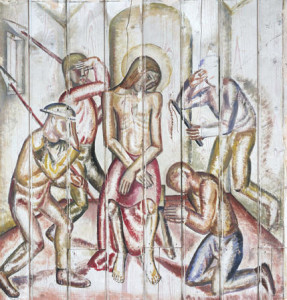

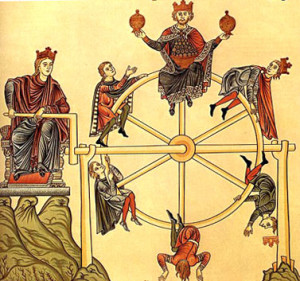

An image by David Jones. He worked out a very sophisticated theory of art and liturgy based on the ‘gratuitous’ nature of a gift and the ‘utile’ nature of instruments.

This is why efforts at liturgical reform that are based in rationalism, trying to help the liturgy “make more sense,” are misguided at best. We only begin to understand the deepest logic of the liturgy when we have become totally transparent to the Divine Will, when our minds have been truly renewed in Christ. And unfortunately, there is some reason to think that, in the West, we have been truncating and rationalizing our liturgical observances for some time, probably coinciding to some measure in the rise of the centralized, monarchical papacy during the high middle ages. Which is to say since the end of the Benedictine centuries (ahem). As active religious life became more the norm and the papal curia became more involved in the standardization of the liturgy throughout Europe, the usual drift has been toward simplification, utility, and so on. The last thing the liturgy can be is utile (David Jones’s wonderful term) or useful. It is divine, and God has no need of spaceships or our worship for that matter. The liturgy is a gratuitous gift to His creatures, a bridge between the creaturely and the Creator. In a utilitarian world, this will be profoundly uncomfortable for many of us (what if Mass started to take two hours? Would we stick it out?). All the fuss about candles, processions, maniples, altar cloths…I agree that this can be irritating, and the liturgical traditionalists sometimes can be their own worst enemies. Perhaps because the tendency even for a traditionalist is to find a water-tight reason why you need this or that thing, to make it make sense, rather than allowing the profound uncanniness of liturgy to break down our human agendas and replace them with the divine.

The liturgy is not utile. It does exist for any end in this creation, which is also why it is eschatological. I hope to have more to say on this point in future posts.

![Christ's Ascension is the founding movement of every liturgical celebration. Now He intercedes for us at the right hand of the Father [Romans 8: 34].](https://chicagomonk.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/ascension-coptic-215x300.jpg)