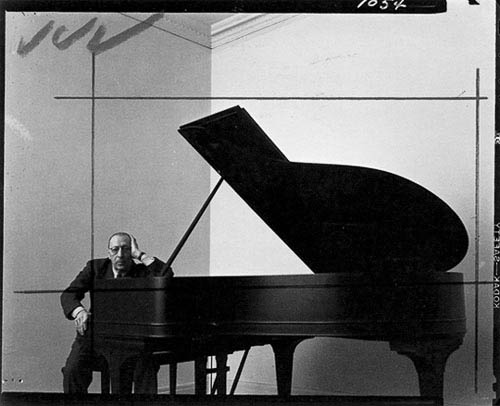

In the first post in this series, we noted that any desire to advance in a practice or craft required renunciations. Professional pianists must refrain from woodworking and gardening, since this will adversely affect their ability to use their hands. Great athletes avoid certain foods, and certain social situations. Clearly, it is important to renounce unhealthy behaviors and attitudes, but sometimes we must also renounce even good things for the sake of better. The shape of such renunciations depends on the goal.

So when St. John Cassian writes of the renunciations, he does so in his third Conference. These renunciations appear in a context. What is the goal that gives shape to these renunciations? What are they meant to make possible? We will fill this in with more detail as we go along, but the primary goal for Cassian is the Kingdom of God. There are many ways to interpret this, and in fact, looking at the renunciations will allow us to understand better what God has planned for us in His kingdom.

Let me mention something surprising. The word “renunciation,” or abrenuntio in Latin, does not appear in the Bible. Cassian quotes the Bible something nearly two thousand times in The Conferences, and makes reference to an astonishing 61 of the 72 books of the Bible. He is also noted for using Biblical terms where his monastic predecessors used Greek philosophical terms.

Cassian is a consummate traditionalist of his time. So his use of the word renunciation in such a prominent place in the third of his Conferences requires us to look elsewhere for this word. And indeed, we discover it in the ancient baptismal rite. The catechumen, having learned to correct his vices and how to grow in virtue, comes before the gathered Church at the Easter Vigil, and he is asked by the priest a three-fold question: “Do you renounce Satan? And all his works? And all his empty show?” Cassian’s renunciations are also three-fold, even though he himself doesn’t refer to the baptismal rite.

There is a second place where three renunciations take place, this time in the Bible, though the word “renunciation” is not used. On the First Sunday of Lent, from the earliest years of the Church, we have listened to the story of Christ’s temptations in the desert. Three times, Jesus says, “No” to the suggestions of Satan. Thus it is that Lent begins and ends with three renunciations.

|

Three Renunciations, Three Sources |

||

| Cassian | Temptation in the Desert | Baptismal Liturgy |

| Country/Wordliness | Vainglorious Ambition | Satan’s “pomp” |

| Kindred/Vices | Gluttony=Gateway to Vice | Satan’s works |

| Father’s House/Idolatrous Images | Submission to the Demonic | Satan |

Instead, Cassian uses the call of Abraham as his template for the three renunciations. When God calls Abraham, still known as Abram at this point, in Genesis 12, he says, “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you.” Cassian then goes on to explain to us what is to be meant by 1) your country, 2) your kindred, and 3) your father’s house. I would like to discuss each of these three renunciations in my three talks. Keep in mind, however, that Cassian’s idea of the three renunciations is progressive, which is to say that each renunciation is more difficult and profound.

We should note that progress for ancient people did not necessarily mean a step-by-step growth whereby one stage was completely left behind as another was begun. Rather, all three renunciations will require a certain doubling back. I will deal with this reality, how the spiritual life is full of stops and starts, circling back, and leaps of insight, in the second talk.

Even so, it was generally acknowledged that human beings had purposes or goals. That we do not appear in the world randomly, but were made for a certain reason, and that this reason could be discovered. This was true for pagans such as Socrates as well as for monotheists like King David or Saint Paul. As the purpose of our life is gradually revealed, as we come to understand it with greater clarity, we make progress toward realizing that goal. That is to say, the achievement of our life’s goal moves from being a potential reality or a merely envisioned reality to being real.

For the purposes of this series of posts, I would like to define the Kingdom of God this way:

Joyfully receiving my life at every moment from God through others.

Notice the passive constructions. This is something that we must learn to allow to happen. The initiative is God’s. Our job is to clear away the blockages from our receptivity toward God. This is not as simple as it seems. This is because we discover what needs to be renounced after and as we discover ourselves loved and forgiven by God. The Apostles received the strength fully to renounce their lives only after Pentecost, only imperfectly before. Jesus taught them during His earthly life, but the full implications of His teaching were revealed only after He returned to them, offering them forgiveness.

We recently installed a new high altar and choir stalls. We had known for a long time that we needed the old ones replaced. But the impetus for the change was the gift of three beautiful icons by a good friend of ours. And this gift opened our imaginations to discover potential in our church building that we might not have thought of otherwise. Had we set out to put in a new altar and then add icons, we probably would have reduced our imaginations to the somewhat run-down church that we already knew. It took a gift from someone else to produce in us monks an awareness of just how run-down our church actually was! And this in turn helped us to notice where we could make real improvements to the building, rather than just patches.

So it is with Christ. When Christ dies on the Cross and returns to us, what He invites us to is not simply a patch on our old life, but an invitation to a completely new kind of life. But just as the beautiful icon suggested to us that it was time to start over in a sense with our church building, so too, the new life that Christ offers us is an invitation to die to the old self. To do this requires renunciations, laying aside our old ways of being, and allowing ourselves to be led into the land that God will show us.

***

You can find an index to all of the posts in this series here.