I have received many positive comments about the article that led our newsletter for Advent, so I would like to share it with a slightly different readership. I will preface this with a few more thoughts of Christmas, and why this celebration led me to my vocation. What gives coherence to the meaning of Christmas for me is the deep mystery of life itself. How is it that we–each of us a self, an “I”–observing the world and “All things counter, original, spare, strange; [Hopkins]” see things similarly, see things differently, see and understand anything at all? How often do we stop and wonder at it all? Something about Christmas always stopped me in my tracks and forced these questions upon me. The answer to this mystery is not the solution to a puzzle, but the sheer gift of love, of shared life and wonder. At the center of all that it, is a God Who wishes to be included in all things with us, our joys, sufferings, our boredom, weariness, excitement, community, loneliness, the whole labyrinth of life that each of us experiences. And in sharing the beauty of all that He created, He does so in most unprepossessing way possible, as a poor child of poor parents in a poor village, but rich in wonder and observation (read any of Christ’s parables and see how He never outgrew the child’s power of noticing things). We need not cross the sea to discover mystery–it is right in front of us and opens the way to participation in the Source of life.

[The article from our newsletter, entitled “Christmas and Everyday Life”]

One of the brothers recently asked me if there was a particular Christmas song that evoked strong memories for me. I couldn’t really answer the question because there are many such carols, in addition to the sublime arias and choruses of Handel’s Messiah and the magical dances of Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Nutcracker. I eventually settled on one carol, not because it is my favorite, but because it somehow summarizes the importance of Christmas to me: O Little Town of Bethlehem.

With a bit of imagination, the music of this lovely carol takes me back to decorating the house in preparation for the holidays. I always wanted to help set out the traditional nativity scene as well as the Christmas “village,” a tradition picked up from my father’s Polish family. We had pieced together this village over several years, and it included tiny houses, into the backs of which were inserted bulbs from strings of lights that would shine through the colored film windows. Miniature cars drove down snowy streets and sat in the parking lot next to the village church (which had a detachable steeple that occasionally was knocked over by our Labrador retriever). A mirror served as a skating rink, and a model train traversed the circumference of the town.

And of course, the were the tiny people there to celebrate winter by skating and skiing. In setting them up, we had to thread a tiny “rope” attached to a sled through the mittened hand of a bundled-up and straining adult. And then there were two blanketed children to be perched upon the sled. A thumb-sized collie ran alongside the family.

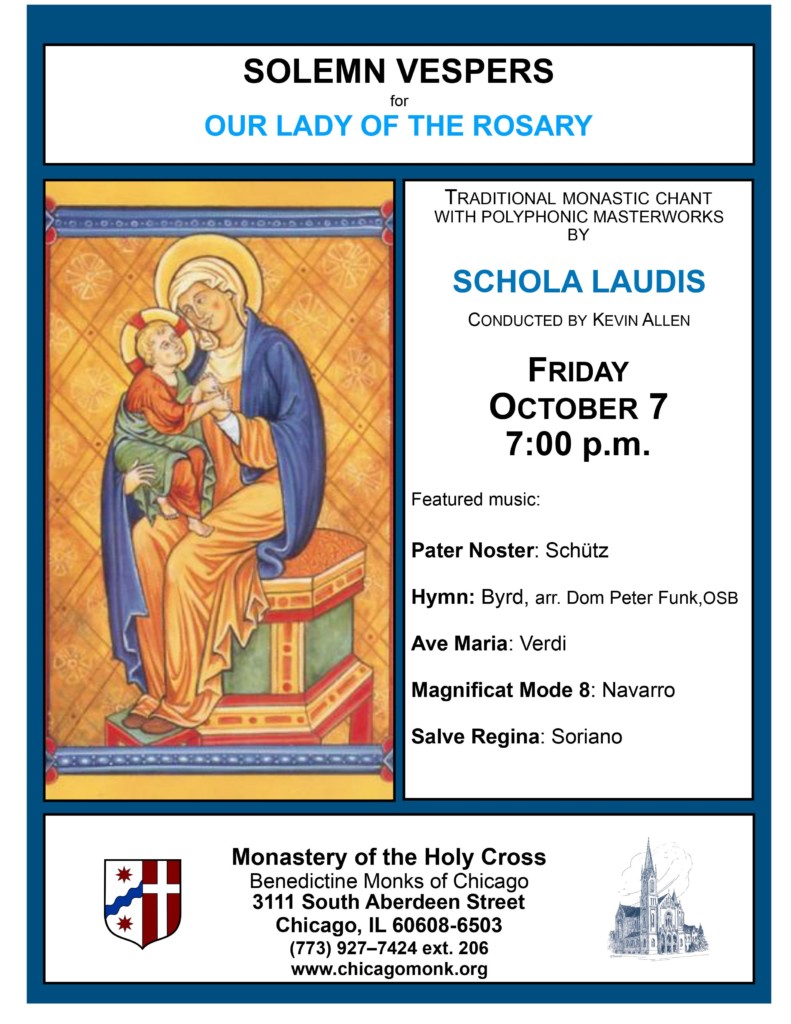

Perched behind all of this activity was, incongruously, the thatched barn giving shelter to the Christ child in the manger, adored by Mary and Joseph, and a motley band of shepherds. A variety of beasts kept the watch. To my eye, there was nothing quite as beautiful as these figurines, especially the shiny apparel of the Wise Men, the haughty camels, and the one poor shepherd, kneeling and offering a few coins resting in a cap in his hand.

Not only were these scenes separated by two millennia; they were not to scale. And yet, somehow, the ensemble spoke perfectly to me of the mystery of Christmas. The Son of God came, not only for the salvation of persons of the first century, but for every human being, for every human community. Not everyone in the Christmas village was in the church at that moment, but the church was there, its steeple pointing the way to heaven, or, in our humble tableau, to the angels singing above the newborn King.

Bethlehem was much like any other village, with its public spaces, rows of homes, families, children, pets, and other animals. When God sent His Son to redeem us, He came, not with spectacular show of “shock and awe,” but quietly, into a small home, beneath the same stars that we see today in the midnight sky. God thereby demonstrated that to be His child, it is enough to be human like anyone else.

The celebration of Christmas eventually had a profound effect on my own vocation. The beauty of God as a child, as an adolescent and young man, making friends, attending family weddings (I attended many weddings, as best man and as a musician)—the whole lot of everyday human life—made Christ especially present to me and made me want to respond by offering my life to Him as best I could, with the hope that perhaps others could experience what I had intuited: that into the darkness and obscurity of our quotidian existence, has shone the everlasting light. Now all the humble details of human life, the joy and tears, the sweat and rest, sowing and harvest, are illuminated from within by God’s Word. And that Word is Love.