When God singles out a person for a special task, He often changes his or her name. Abraham, Sarah, and Israel in the Old Testament, and Peter in the New take on a different identity when God calls them forth. Von Balthasar has this lovely reflection on this phenomenon:

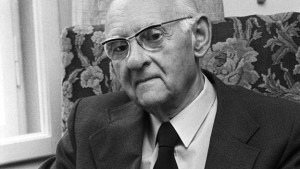

Hans Urs von Balthasar, 1905-1988. Pope Saint John Paul II intended to create him as a cardinal, but he died prior to the ceremony.

Simon the fisherman could have explored every region of his ego prior to his encounter with Christ, but he would not have found “Peter” there….Then Christ confronts him with [his mission], unyielding, demanding obedience, and it will be the fulfillment of everything that, in Simon, vainly sought a “form” that would be ultimately valid before God and eternity. —Prayer

God can confront each of us with a mission that we ourselves could not have predicted or discerned by “casting round our comfortless” interior, exploring every region of our ego. This is a radical idea. Our more typical notion of authenticity is based precisely in seeking for clues in the corners of our inner psychological Simons. Simon needed the man Jesus of Nazareth to say to him, “Come, follow me, and I will make you a fisher of men.” Otherwise, he would never have become Peter. He needed to be “made” by Christ anew, and the old man, the fallen man Simon, had to die so that this Peter, who is capable of things that Simon would never have imagined himself capable of, might begin to flower and put forth fruit.

Wax on; wax off….The Karate Kid can’t understand the utility of waxing cars until he becomes proficient at it. He must make an act of trust in mysterious Mr. Miyagi.

I wrote yesterday that in order to become proficient in a tradition, one must undergo a kind of conversion. One must become a different kind of person. And this conversion depends on an act of faith in a teacher, who may ask me to do things that I don’t understand. Obedience need not be “blind,” but will be more effective when it is accompanied by love and devotion to the teacher. After all, what we are seeking is not only self-fulfillment, but sympathy with the master. “It is enough for the disciple to be like his teacher [Matthew 10: 25].” The goal of Christian conversion is to mature into our “Christ-self,” to become members of Christ, to put on Christ, and this requires us to be called out of ourselves.

Most dedicated Christian know all of this. Where it becomes truly demanding is when we recognize that the calling really must come from outside, and therefore may well be more authentic when opposed to our inclinations and preferences. When we think of discerning God’s will, is it not the case that we often equate God’s voice with some interior conviction? Obedience to another person is a real undoing of the self, because it prevents us from confusing our own wishful thinking with God’s plans. And it comports with the notion that we must become different kinds of persons, rather than simply developing what we ourselves identify as our latent talents. “Consent merits punishment; constraint wins a crown,” Saint Benedict teaches [RB 7: 33]. He is quoting from the acts of the martyr Anastastia. In this connection we see how even allowing for obedience under unjust circumstances can be more fruitful than following our own inner light, for this docility allows God to act and conforms us more closely to Christ Himself.