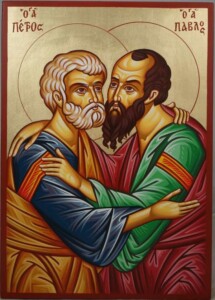

“Behold! Now is the acceptable time; behold, now is the day of salvation! [2 Corinthians 6: 2]” We sing this text from Saint Paul every Sunday morning during Lent. Paul’s impassioned exhortation reminds me of the words of another Apostle. Saint Peter, in his first “homily” on Pentecost morning, says to the crowd, “Let all the house of Israel therefore know assuredly that God has made him both Lord and Christ, this Jesus whom you crucified [Acts 2: 36].”

In both cases, the Apostles Peter and Paul speak with great urgency. An immeasurable change has just occurred. A man has been raised from the dead and taken up into heaven. Now is the time to act: for Saint Paul, “We beseech you on behalf of Christ, be reconciled to God [2 Cor. 5: 20]”; for Peter, “Repent and be baptized [Acts 2: 38]!” This is our chance to make things right with God.

In both cases, the Apostles Peter and Paul speak with great urgency. An immeasurable change has just occurred. A man has been raised from the dead and taken up into heaven. Now is the time to act: for Saint Paul, “We beseech you on behalf of Christ, be reconciled to God [2 Cor. 5: 20]”; for Peter, “Repent and be baptized [Acts 2: 38]!” This is our chance to make things right with God.

Can we find this urgency in Lent? Lest we think that the acceptable time has come and gone,we might first note that Paul is writing the Corinthians perhaps twenty-five years after the Resurrection. The acceptable time is always now. The Church dramatically and starkly moves us to action in the liturgy of Ash Wednesday. To dust we shall return, at a time that we cannot yet know. There is no time like the present to repent. In just over six weeks, we will re-energize our baptisms by renewing our promises to serve God and reject evil. What if, in the intervening time, we were able to welcome God’s grace so as to be more saint-like when we pass through the darkness of Good Friday to the light of Easter?

There is another reason for urgency. We are discovering more and more each day, perhaps to our dismay, just how badly in need our world is of moral and spiritual renewal. The extent of evil in the world can be demoralizing. This Lent is a good time to offer our own acts of self-denial for the reparation of the harms done. The power of two billion Christians doing acts of penance and praying fervently is a good place to start tipping the scales back. We are living anew the need to “repent and be baptized,” to be reconciled to God, not for our sake only, but for the sake of the whole world. May God grant us all a holy Lent!