My last post ended with a question. Once we get some emotional separation from our thoughts, and we use our newfound perspective to assess our thoughts, how do we determine which ones are good and which ones are bad? To answer this question, I would like to look more closely at where our thoughts come from, and then offer some ideas on how to separate out good thoughts from bad.

Not only are we not our thoughts, but many of the thoughts we have don’t originate with us. This might sound surprising at first, until you give it a little thought (so to speak). Human beings use language to assist us in our thinking, and the words that we use are not our own. So to some extent, the shape that our thoughts take depends on the language we grow up using, and our facility in using it. We learn a lot about the world from what other people tell us. How we think about politics depends on which sources of news we read, how much we’ve learned about history and civics, and so on. In today’s world of hyperconnectivity, we often passively absorb all kinds of thoughts and feelings from advertising, movies, and social media.

So the very idea that what I happen to be thinking or feeling at the moment is somehow “me,” or even “how I tend to think” hides from us the important fact that a good deal of our interior life is borrowed from sources external to our minds. Ancient monastic tradition understood this well. The monks of old referred to good thoughts as “angelic” (literally “messages” from God), and darker thoughts as “demonic.”

Our Lady trained herself by meditation on Israel’s scriptures to recognize the voice of an angel when Gabriel was sent to her.

Lest this talk of angels and demons sound too fantastical, let’s continue to unpack the phenomenon of thinking. Many of you know that before I entered monastic life, I was a professional songwriter. The first time that I experienced writers’ block, I started wondering about where my ideas for songs came from. Even today, when I walk in a crowded place, I tend to experience melodies arising internally. Sometimes I still wake up with songs going through my head that I’ve never heard before. In the modern world, we often celebrate persons whom we think of as “original” or “creative.” Now, these last two words are slightly dangerous from a theistic perspective, since we technically are not the origin of ourselves. Therefore we are never fully the origin of any product of our own thought or labor. Nor can we create, in the strict sense. So the question arises again, where do “creative” thoughts come from?

Before the notion of creativity became current, Western culture prized “inventors.” An invention is literally something that somebody “found” (Latin inventum, a thing that was found). Inventiveness arises from attentiveness, awareness, and a sympathy for things as they already are. Bach composed a number of “inventions,” and, as a devout Lutheran, he very much understood himself to have been a discoverer rather than a creator. Similarly, Stravinsky did not see himself as creative in the literal sense of the word. Rather, he was a “discerner.” He sorted through his many inspirations, and he kept the good and threw away the bad. Such is our work when we discern our thoughts.

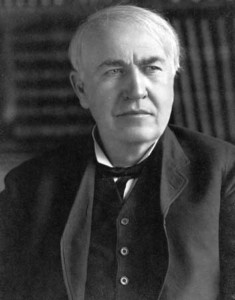

Thomas Edison was an inventor. One of his most important virtues was perseverance in the face of failure. He tried out numerous materials for his light bulb filament before succeeding. Musical “inventors” follow a similar procedure. A great composer of music is someone who has lots of inspirations…and throws away the bad ones (which might be most of them), and keeps the good ones.

Someone like Edison has an advantage over composers when it comes to separating the good inspirations from the bad. Either the filament lights up, or it doesn’t. How does a composer know when his piece “lights up?” Because a good composer has listened to lots and lots of good music, and he knows whether a piece is good or bad.

Learning to recognize what makes a song, a singer, or a symphony great allows me to apply the same standards to my own inspirations. Two examples: listening closely to the horn arrangements by the band Chicago taught me how to layer melodies within a texture to create depth that the ear might not hear on a first listen, but will be “felt” as more coherent. Paying attention to Joni Mitchell’s earlier songs (“For the Roses” is my favorite album of hers) taught me something similar: how the range and shape of a melody can convey emotional nuance. So, when my own compositions feel stale in some way, it’s often because I haven’t used these layering and shaping techniques to anchor the overall effect. And I recognize that feeling of staleness because I’m comparing my song to good songs.

A good composer, then, trains herself by immersion in good music, to be able to look objectively at her inspirations.

A composer has inspirations, and we have thoughts. The mechanism is, for our purposes, the same. A good composer trains herself to like good music, and to apply the same standards of excellence to her own compositions. We can train ourselves to like good thoughts. We do this by immersion in thoughts of proven worth. For a Christian, this would mean immersion in the world of the Bible (especially the New Testament) and the spiritual classics like Confessions or Saint Francis de Sales’s Introduction to the Devout Life. It also means keeping at arm’s length more damaging influences.

If a reader were to ask me what two practical steps anyone could take today to make progress in the discernment of thoughts, my answer would be: 1) disconnect from the news and social media, and 2) read Saint Paul’s letter to the Philippians. The entire letter is worth your time, but let’s start here:

“Whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is gracious, if there is any excellence, if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things [Philippians 4: 8].”

I offer this one passage not as a shortcut to a fleeting mood of optimism. Rather, Saint Paul is offering a baseline of good thinking. Compare his exhortation to the actual state of your mind. On what might you reflect in order to find nobility and excellence? Which thoughts might you reject as untrue, dishonorable, or unjust? Why doesn’t Saint Paul urge you to think about your resentments or all the bad things that people do? Is it possible to be aware of evil in the world, take note of it, but not allow it to be the thrust of your thinking? Now you are practicing good interior hygiene.

Like learning to enjoy good music, training ourselves to “refuse the evil and choose the good [Isaiah 7: 14],” requires a commitment to change. What better time to start than in our present circumstances?

In an upcoming post, we will look at how to influence our thinking by changing our behaviors. For now, here’s a remarkable combination of guitar texture, vocal delivery, supple melodic ideas, and ingeniously poignant lyrical imagery. This is a song that has made a big impact on my thinking about musical excellence (though not as much impact as Saint Benedict has had on my thinking about spiritual excellence!).