Professor Peterson combines the toughness of small-town Alberta with the intellectual challenge of Nietzsche and Jung.

Recently I gave a talk for Theology on Tap on the phenomenon of Jordan Peterson. Peterson is a clinical psychologist and University of Toronto professor. He recently published his second book, a kind of self-help book for millennials, especially millennial men. Hundreds of thousands of people watch his Bible study videos, in spite of the fact that he is not a typical believer. I found out about him through a Catholic friend about a year ago, and I immediately recognized his appeal to young men. Let me explain some of that in today’s blog post, which will be the first installment of an expanded version of my talk.

I grew up somewhat ambivalent about the concept of manhood. My father left the family when I was fourteen after long struggles with alcohol and other demons, leaving me as the only male member of the nuclear family. A certain salvation was opened up for me by the families of my two closest friends. Mark was the oldest of four boys, and he and I became basketball fanatics. Jon was the middle of three boys and was the captain of our high school football team. So sports became a place where I identified and found a certain comfort with masculinity. I lettered in baseball and cross country and even became the morning sportscaster at a local radio station, having to be at work every morning by 4:00 a.m. before school, tearing the latest scores off of our dot-matrix UPI feed, and reading them on air each hour.

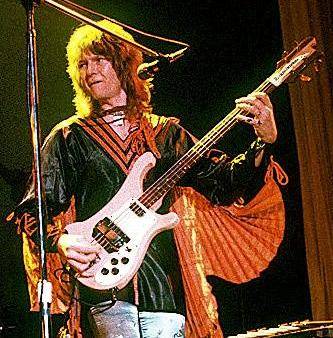

Chris Squire of Yes: one of my models of masculine artistry, with an acceptably high-pitched (English) voice.

Rock music became another place where I felt comfortable expressing masculinity. I was a talented musician as a youngster, but music was often considered an activity for girls. I had a high, squeaky voice that never really broke. I discovered that my comfortable singing range fit well in genres like prog rock (bands like Rush, Yes, and Boston; my closest vocal doppelgangers were Peter Cetera and Brad Delp), not to mention heavy metal (which I didn’t much care for).

The struggle I was experiencing was not merely a personal one resulting from my family situation. I was already experiencing a broader societal ambivalence about masculinity, an ambivalence that has only worsened since I graduated high school thirty years ago. My seventh-grade religion teacher, a former religious sister, was a notorious early-adaptor to the anti-boy animus. She especially didn’t care for me. I found this amusing–my “bad boy” persona in this particular class turned out to be more attractive to the girls in class than my more straight-laced personality outside. But my point is this: in 1982, she openly taught ideas that have become quite normal in 2018, that boys are too rambunctious, men have illicitly profited from the Patriarchy at the expense of women (and it’s payback time), men are too competitive and this is bad, etc. Her approach did not win great favor back then, but I suspect it’s something like orthodoxy in many educational situations today.

I suspect this because I work regularly with young men discerning religious vocations, and I’ve discovered that one of the challenges facing men’s monasteries today is helping new recruits to embrace their manhood as a legitimate way of following Jesus Christ. On one level, this sounds incredible–weren’t the Apostles salt-of-the-earth fishermen with sympathy for the anti-Roman guerilla uprisings of the era? Be that as it may, study after study finds that most people believe that Christianity embodies and encourages what Jordan Peterson would identify as more typically female traits like agreeability, and togetherness. In other words, it’s not for men. If you do experience a call to the priesthood or religious life, you must be a strange sort of man.

Our Father Brendan’s blood brother Tim is a retired Marine drill sergeant. Father Brendan and I frequently have marveled at the way in which the Marines can take an eighteen-year-old and within a short period of time transform him into a commander of men, someone who is courageous under fire, loyal, dutiful, and a team player (which is not the same as being non-competitive). We began to seek out advice from Sergeant Creeden, and we took to watching videos of BUDS training with our younger monks. Many monastic founders (Saint Pachomius, Saint Martin of Tours) began their lives as soldiers. The Rule of Saint Benedict presumed that monastic life is a form of spiritual warfare. We miss this because we forget that the word “service,” means not only helping other people in need during peacetime. It also refers to the military.

Saint Martin of Tours, in his famous act of charity.

It’s hard to deny that our culture presently discourages young men from developing the traits that soldiers need: courage can only be gained, after all, by risk-taking. We often identify risk-taking as a pathology needing medication. Competitiveness, by which boys and male adolescents naturally form themselves into hierarchies of merit and excellence, is frowned upon. Scores of young men are expressing high levels of frustration as natural masculine traits are denigrated and their achievements are belittled by a metastatized political correctness. That group of men I’ve just described has been labeled recently as the “Jordan Peterson Demographic.” In the past two years, many from this demographic have discovered the guru who is challenging them to step up and take ownership of their lives. His recent book, Twelve Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos, has been described as a “self-help book by a culture warrior.”

In the next post, I will ask what it means to ask for help.