This past week, I was invited to offer a day of reflection at St. Mary’s parish in Greenville, SC. The entire event was an edifying one, with beautiful liturgies and Stations of the Cross on Friday evening. Here, I plan to reproduce and perhaps expand a bit on the talk. This first post will serve as an introduction, as well as an index for future posts (See the very bottom of this page to see an updated listing of the installments in this series.)

The organizer of the event suggested that I break my talk into three parts. Being of a neo-Medieval mindset, I immediately began to ask myself which triad of topics I should choose. The Holy Trinity? The Paschal Triduum? The theological virtues? Since it is Lent, and since I thought it important to touch upon monastic spirituality, I decided to reflect on the three renunciations, according to St. John Cassian. We are all familiar with the idea of “giving up” something for Lent. Why do we do this? Is there something to this other than a temporary regime of self-improvement?

I will mainly focus on Cassian’s third Conference, but a fuller explanation of the renuciations requires that we touch on other monastic literature. The whole text of the Conferences is on-line and can be found here. To find the third Conference, follow this link.

As we will see a bit further on, Cassian was a kind of spiritual grandfather to Saint Benedict, the founder of our order. Saint Benedict says that the entire life of a monk should be like a continual Lent. If this is so, perhaps we can turn this around and say that Lent for the laity should be a taste of monastic life. In other words, the renunciations that we will examine, while intended originally for monks and nuns, should be adaptable to those outside the cloister, if we give them a bit of effort. And I believe that making this effort will help us to enter more fervently into this year’s celebration of Easter.

It is worth noting at the outset that Benedict also mentions “joy” twice in his brief chapter on Lent. Therefore the renunciations are not meant to plaster gloomy looks on our faces, but to give us renewed clarity of purpose in our lives by clearing out everything harmful or even unnecessary to flourishing.

The truth that we all make renunciations in all walks of life. This is a matter of prioritizing and schematizing life. Renouncing certain possibilities does not mean that they are evil. Marrying one man does not make all other men bad; but it does require renouncing certain types of relationships with them. Choosing a college requires renouncing attendance at others, but does not render all other colleges deficient.

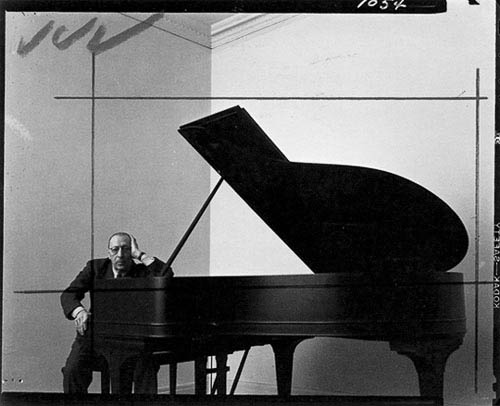

As a composer, I take inspiration from something that the great Igor Sravinsky once wrote, in The Poetics of Music. It is worth quoting at length:

The creator’s function is to sift the elements he receives from [imagination], for human activity must impose limits on itself. The more art is controlled, limited, worked over, the more it is free.

As for myself, I experience a sort of terror when, at the moment of setting to work and finding myself before the infinitude of possibilities that present themselves, I have the feeling that everything is permissible to me….

Will I then have to lose myself in this abyss of freedom? To what shall I cling in order to escape the dizziness that seizes me before the virtuality of this infinitude? … Fully convinced that combinations which have at their disposal twelve sounds in each octave and all possible rhythmic varieties promise me riches that all the activity of human genius will never exhaust… I am always able to turn immediately to the concrete things that are here in question. I have no use for a theoretic freedom. Let me have something finite, definite–matter that can lend itself to my operation only insofar as it is commensurate with my possibilities. And such matter presents itself to me together with its limitations. I must in turn impose mine upon it….

My freedom thus consists in my moving about within the narrow frame that I have assigned myself for each one of my undertakings.

I shall go even farther: my freedom will be so much the greater and more meaningful the more narrowly I limit my field of action and the more I surround myself with obstacles. Whatever diminishes constraint diminishes strength. The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees oneself of the chains that shackle the spirit.

If this is true in music, how much more in the Christian life! What are we doing to shackle the Holy Spirit. In our next post, we will hear from Cassian on this important question.

Below are links to the other posts in this series: