Our next celebration of Solemn Vespers with Schola Laudis will be this Saturday, July 28. What follow are my program notes for the occasion. For more information, click here.

Gregory, Servant of the Servants of God, evangelized England, gave birth to Gregorian chant, and wrote the Life of Saint Benedict.

Saint Gregory the Great is one of the few late Western Fathers whose works were also highly esteemed in the Christian East. There, he is known as “Dialogos,” the writer of the great Dialogues. One-quarter of this famous collection of the lives of saints is given over to Saint Benedict, which means that Gregory holds a special place in Benedictine monasticism.

Without a doubt, his most influential work in the West is his monumental Moral Reflections on the Book of Job (Moralia in Job), a line-by-line commentary on the thorny wisdom book that recounts the misfortunes of that just man, whose life becomes a battleground between God and Satan. Alas, only in the last few years has a top-notch English translation become available, thanks to the work of the Trappist Brian Kerns.

We monks are in the middle of reading through the book of Job, which we do every even-numbered year at the early-morning office of Vigils. It would be an understatement to say that it’s one of the more challenging books of the Bible. No wonder that Gregory’s close friends, before he became pope, urged him to publish his lectures on this text, which he did shortly after his elevation to the See of Peter. The text was so popular that, in spite of its enormous length (roughly the size of Augustine’s City of God and Confessions combined!), it was swiftly copied and distributed throughout the growing numbers of Benedictine and other monasteries in the seventh and eight centuries.

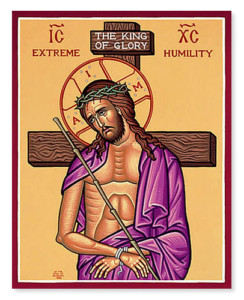

Like all early Christians, Gregory read Job through ‘typology’ and, as such, tended to identify him as a type of Christ. Just as Christ emptied Himself of the prerogatives of divinity to join humanity on the “dunghill” of this little earth, Job lost all of his possessions and his family. As Job was afflicted with terrible physical suffering, Christ endured the torment of the Cross. Christ was denied by his friends and taunted by the religious authorities of His time, much as Job’s friends, who come to comfort him in his affliction, wind up his adversaries, punishing him more by their morally intransigent insistence on the justice of his misery. Finally, Job’s final justification by God is a clear foreshadowing of the Resurrection of Jesus, his “justification in the Spirit [cf. 1 Timothy 3: 16].” Job becomes a priest for his friends, reconciling them to God by his sacrifice, as Christ has become our great High Priest.

Milton. Not only does Satan get all the good songs, but he gets the coolest engines besides.

This hardly summarizes the wide-ranging lessons that Saint Gregory draws from the long debates and the enigmatic response that God gives to Job at his restoration. It does, however, give some indication of the difficulty for modern persons to enter into Gregory’s interpretation. In modern times, Job has become a locus classicus of the problem of theodicy, the problem of explaining how evil coexists with an omnipotent and benevolent God.

The medievals simply didn’t trouble themselves with this question. We may not find that very attractive, but it might also do us well to look more closely at the overall cultural context.

Milton provides an interesting bridge. By the seventeenth century, he felt it an urgent task to “justify the ways of God to men,” in Paradise Lost. Monks tended to be somewhat less interested in this abstract, almost Gnostic concern. Monks were more interested in knowing God.

Contrast Saint Anselm († 1109), whose meditations on the Incarnation are read by some today as prefiguring the issue of theodicy. His theological treatises are always dialogues with God, “faith seeking reason.” God, who is Love and is loved, needs no further justification. Not only is Job a type of Christ, but Christ’s loving embrace of the Cross in our human flesh is the answer to all suffering, no matter how senseless it appears. Job’s calamity and restoration make up one privileged path into the mystery of the encounter with God, Who reveals Himself to Job. Tellingly, God takes Job’s side, and Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar, those who busily tried to justify God’s ways to Job, hear instead, “You have not spoken of me what is right, as my servant Job has [Job 42: 7].”

In the Benedictine Office, the Saturday evening Vespers liturgy almost always takes its Magnificat Antiphon from the Vigils readings of the coming week. This week, we will conclude this mysterious book, and hear Job’s remarkable confession, “I had heard of you by the hearing of the ear, but

“Come to me, all you who labor and are heavy-burdened, and I will give you rest.”

now my eye sees you; therefore I despise myself, and repent in dust and ashes [Job 42: 5-6].” This evening’s opening motet, Palestrina’s Vir erat in terra, is an offertory, originally connected to the Twenty-First Sunday after Pentecost. The link between Job’s suffering and the offertory of the Mass makes clear what Gregory the Great taught: that the reconciling victim is figured in all human suffering.