Fear is a part of our bodily constitution. It comes with being a member of the animal family. In evolutionary terms, it has served us and our fellow animals well. Fear rapidly mobilizes our energies to face down danger or to flee from it. Both reactions give us a better chance of surviving immediate danger. This means that natural selection has favored the cultivation of the fear-response in us.

“Nothing resembles an angry cat…more than an angry cat.”–Anthony Storr, “Aggression” The breakdown of distinctions caused by fear, anger, and violence makes reasoning impossible.

For us rational animals, however, fear also presents specific dangers of its own. When I was in high school, my family had a beautiful but terrifying dog, a black Labrador/German Shepherd mix. She was a great guard-dog for a single-mother family, but her attack instincts were sometimes, let’s say, inappropriate. Once, when one of my mother’s piano students came for her lesson and rang the doorbell, our dog shattered the glass of the front door in warding off this thirteen-year-old girl student. Our dog frequently would get very upset about the presence of my male friends, though once she decided you were safe, she was as devoted afterward as she had been suspicious before. The difficulty for us is that there were few things that we could say to our dog to convince her that her responses were irrational. This is why Aristotle refers to humans as rational animals; among the members of the animal kingdom, we have learned how to temper the fear response by muting it, thinking through the situation, and then deciding whether fear is warranted. If it is, we have a larger repertoire of responses than fight or flight. We can make a plan that takes into account potential long-term effects of any hypothetical actions. Dogs, intelligent as they are, lack most of what makes this possible for humans.

In Catholic moral theology, we speak of the “age of reason.” Very young children do not yet have the full faculty of reason, and, as a result, tend to act on the promptings of feelings. One of the responsibilities of parents is to respond to the emotions of children in such a way as to facilitate the emergence of reason in the child. As parents know, the ongoing achievement of rationality is directly linked to an ability to manage one’s emotions, especially fear. Maturity is marked by rational reflection and reason-based decision making. Immaturity is marked by impulsivity and emotional reactivity. Another shorthand way to summarize this would be to say that the mature adult tends to respond to life, whereas the immature person tends to react.

When we permit ourselves to react, or even to overreact, we move in the direction of immaturity and even infantilization at times. Adult temper tantrums are no different than kid temper tantrums.

Mature persons are not therefore unfeeling, however. We will still have the immediate bodily responses to typical stimuli: fear, joy, anger, hunger, and sexual arousal. What will change about us is that we will know how to anticipate the trajectory of these feelings. We will know how to step back from immediate engagement, especially from those emotions that are most likely to lead to trouble if acted upon. The stimulus and its initial emotional response, in other words, will just become more information. That first impulse of fear, or perhaps more often, a sense of something being not quite right, is often a signal. Perhaps we need to pay attention to our surroundings a bit more perceptively in order to judge correctly what is going on. Some of us are better at making these detections in personal relationships, accurately reading body language, for example, to gauge what is being left unsaid. Others tend to excel in situational awareness, the ability to spot potential dangers before they arise, and to sense the presence of danger by knowing how to interpret inconsistencies in large-scale spatial arrangements. This is a good, mature use of initial emotional responses or “gut feelings.”

All of the above helps to explain some difficulties facing us as we try to make prudential responses to the pandemic. The worst-case scenarios present significant dangers to our whole way of life. As I wrote earlier, fear is not an unreasonable response to a number of possible futures. But if we allow fear to become chronic, if we continually marinate ourselves in the scariest projections, we run the risk of making our response less mature and less rational. In point of fact, we have, as we all know, lots of time to decide how to deal with the pandemic. We are not faced with a saber-toothed tiger ready to devour our children, a danger that requires a decisive, forceful response.

The quarantine that most of us are experiencing ratchets up chronic fear in another way. Every fellow human being is to be treated indefinitely as a potential vector and danger. That means that grocery shopping has suddenly been transformed into a dangerous activity. Every single action that requires us to come into proximity with someone else, we are told, is dangerous. This itself seems like a recipe for chronic fear and, therefore, unfortunately, immature responses to the actual threat.

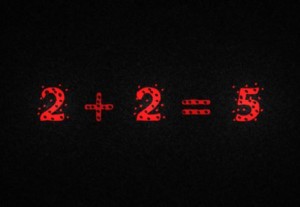

George Orwell warned about the dangers of a breakdown in trust between fellow citizens, and the relation of this breakdown to the breakdown of reason.

This situation is clearly unsustainable and poses, in my view, much more dangerous long-term consequences. If we continue to treat all social interactions as fearful, we run the very real risk of infantilizing ourselves and making rational discourse impossible. When reason is not an available option, we are left only with power and force. Totalitarian governments know this, and so the cultivation of fear is an ineliminable feature of all dictatorships. Mind you, I am not saying that we are living in such an environment—yet. But at the very least, it seems important to me to treat the resumption of social interactions as a necessary goal, and to find ways to discuss with others in our extended families, neighborhoods, and workplaces, goals for making this happen as safely as possible. This will work most effectively if, in our personal lives, we are taking steps to cultivate our own rationality and maturity by reflecting regularly on what kind of information we really need (rather than letting hyperlinks lead us by the nose into what an anonymous person wants you to read, perhaps for motives of advertising revenue) to make informed decisions, and finding ways to identify the sources of fear and to assess them as we would any other threat.

Last of all, we should aim to hold before our minds eye the examples of heroes whose lives we wish to imitate. This is one reason that I urge our monks to read the lives of the saints frequently, and to make friends with them. The saint is a person of “heroic virtue,” and therefore, courage. In my next post, I would like to share with you my thoughts about why the saints are also models of rationality.