Saturday, my host family took me to visit the town of Ely, which is near Cambridge where I’m enjoying a short sabbatical. Much of the medieval cathedral and its monastic buildings are still in existence. While I was there, the Worchester Cathedral Chamber Choir offered a short concert of pieces by Elgar, Handel, John Ireland, and others. Afterward, we all had tea. It was a splendid day.

Articles tagged with nominalism

On Precursors and Crumbling Walls

A few weeks ago, I compared Jordan Peterson with the medieval theologian Peter Lombard. I didn’t go into great detail on my own intuition in this matter. After some ill feelings about the analogy, I’ve come to reaffirm it in my own mind.

Socrates vs. Nietzsche

[Note: The following is the first entry in my new category of “jottings.” These are totally random observations based in my reading for larger projects. They will probably be, for the most part, either technical or expansively allusive in character and unapologetically so. Regular readers might choose to skip these, but they are intended to provide background for what I hope will be more popular writing in the main posts of this blog.]

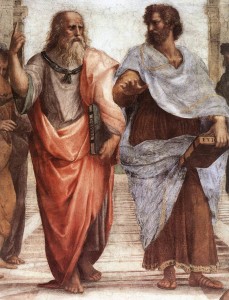

Studies in classical philosophy often contrast Plato with Aristotle. Raphael’s School of Athens shows Plato pointing up toward transcendent reality, the realm of the forms, more real than what senses can perceive. Aristotle, while not exactly pointing down, does appear to be tethering the conversation to what “common sense” can perceive of the only world that we can be confident of sharing with other rational beings. Students of these two philosophers often take sides, preferring one to the other, as though Plato’s greatest student, Aristotle, either refuted or strongly corrected his teacher, or, on the contrary, sadly eliminated all transcendent reference from the joy of philosophizing.

The truth is more complex. What I would like to note is that champions of Aristotle, who use the great man’s teachings against Plato and Socrates, surely do so unjustly. Let me focus on the figure of Socrates, as he is known to us from Plato’s writings about him. When Socrates came on the scene in Athens, he posed himself as an opponent of “common sense.” Yes. But why? I think there were two related reasons. First of all, he opposed a complacent, unexamined use of what passed as common knowledge. This was highly problematic in the quickly changing political atmosphere of his time. Outdated and worn-out ideas lazily copped from Homer’s two masterpieces, The Iliad and The Odyssey did not fit the reality of a budding urban empire.

Socrates also recognized that such complacency in the world of ideas left the people of Athens open to manipulation by demagogues. Such manipulation was openly practiced by the Sophists, the loose school of rhetoricians who “made the worse appear the better reason.” Now, so as not to be too hard on the Sophists, let us note that among the changes in Athenian culture from the heroic age of Homer to the progressive world of Socrates’s day, was a growth in the use of impersonal law to settle disputes. The problems with the legal culture will be a later target of Plato’s, in one of his non-Socratic dialogues. In Socrates’s immediate context, he saw that this reliance upon customary law was not conducive to any attempt to examine truth itself. Many of Plato’s dialogues rehearse Socrates’s method: pick a fight with a Sophist and demonstrate that the Sophist can’t produce a coherent explanation of the actual meaning of the words he is using. In other words, demonstrate that the Sophist tendency is to use words as tools for the achievement of personal goals by using them to manipulate his hearers.

Now let me note here that the theme of manipulation is of a piece with emotivism. Alasdair MacIntyre says that emotivism entails that there be no distinction between manipulative and non-manipulative relationships. That is to say, in our world, sophistry has returned largely unopposed, though we are not often aware of it.

Back to my narrative: Plato recorded and inherited Socrates’s technique and attempted to further the pursuit of truth in his own way. His painstaking accounts of the drama of Socrates’s life and the drama of Athenian society did much to clear away the fog of fuzzy, self-serving, manipulative reasoning. Perhaps he faltered a bit when trying to pin the idea of truth to the transcendent realm of forms. But his work made possible Aristotle’s astounding success in generating a durable realism, or at least something like a technique for separating specious claims about the world from more verifiable claims.

Thus began the arc of Western philosophy, and it apparently continued until the advent of Friedrich Nietzsche. He set the tone for the dismantling of Western philosophy with his remarkable work The Birth of Tragedy. Historians criticize his handling of materials, but he was astute enough to vilify Socrates and locate a turning point in Socrates’s Athens. In Nietzsche’s understanding, Socrates’s thirst for genuine truth was either pie-in-the-sky naivete or perhaps a cynical manipulation that claimed for itself the mantle of truth–which at least the Sophists generally had the good taste to avoid. For Nietzsche, Socrates inaugurated a long desert in which Western culture imagined itself bound by truth, but in fact deluded by this claim into a hideous blindness.

I believe that Nietzsche was perceptive in this claim, though not in the way that he intended. His “Hermeneutic of Suspicion” and “unmasking” of the hidden motives behind appeals to “truth” accurately described, not Western philosophy as such, but rather the particular situation of late nineteenth-century European academe. In other words, Nietzsche was, quite against his intentions, calling attention to the fact that European philosophy had fallen away from its traditional vocation of furthering the durable realism that the founders–Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle–had initiated. And desiring to call a spade a spade, Nietzsche proposed that we go back to acknowledging that rhetorical manipulations are all that we have.

As I suggested, my belief is that Nietzsche perceived that claims to truth by his contemporaries in philosophy really were infected with the complacency that Socrates opposed. How did this happen? It was a slow process, but my own biases lean toward pinpointing the nominalist revolution of the fourteenth century as the beginning. I would also note that this has its roots in the thinking of William of Ockham, who is generally considered to be one of the originators of nominalism. This was at a time when the connection between the liturgical life and the university life was considerably weakened. I don’t exactly like to blame William, since he inherited a number of tricky problems that resulted from institutionalized in-fighting between Dominicans and Franciscans in the early fourteenth-century university. But it does seem here that the first break between words and durable meaning is introduced.

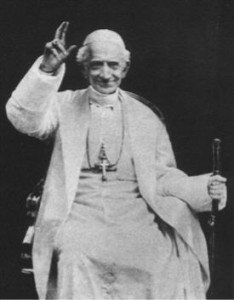

It is worth noting that Pope Leo XIII seemed to have a similar intuition as Nietzsche, and perhaps a more accurate awareness of the reality of the breakdown in philosophy. In his encyclical Aeterni Patris, he insisted that seminary education return to Thomas Aquinas, two or more generations before Ockham. This set the stage for the amazing insights of the “New Theology” of the early twentieth century. Alas, just as we were reaping the fruits of this greater theological realism, seminary educators turned their back again on Thomas (who is regarded even by the non-theologically inclined, as one of the greatest, if not the greatest, of the interpreters of Aristotle). I am not advocating freezing philosophy in one thinker or time period; ironically what Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and Aquinas offer, if correctly understood, is not a complacent position of authoritative power, but a humble method for uprooting the false and lazy assumptions that steer us from the truth. And lazy thinking leaves us open yet again to manipulation by potentially unfriendly powers.

Who’s MacIntyre? Why Virtue?

Seven or eight years ago, I was invited by a group of priests of the Marquette (Michigan) diocese to give a series of talks on music and morality. They were very receptive to my approach and suggested that I might set down my thoughts in a book. Hence the memoir I mentioned in the previous post. I chose the memoir format because music and morality are so difficult to write about in the abstract. And indeed, I more recently gave a similar talk at the University of Virginia’s St. Anselm Institute and faced some tough questions which, to be honest,

Lex orandi, lex credendi…hoc credimus?

In a recent post, I suggested that we can learn how to pray by listening attentively to the prayers of the liturgy. I used the example of the long, and quite beautiful closing prayer of the Major Rogation. The idea of learning prayer from the liturgy is not at all new; I’m stealing it from the Church Fathers. It’s just their thinking can be remote from us. There has been a linguistic drift over the centuries, and traditional words have slowly taken on slightly different meanings, making it more difficult to understand traditional teachings.

Let me give an example. Many Catholics have heard the phrase ‘lex orandi lex credendi‘, which means ‘the law of worship is the law of belief’. This fifth-century saying hold that we believe what we believe because we celebrate the liturgy in the way we do. This seems to suggest that changes in the liturgy should be approached with extreme caution. More than that, to reorient the liturgy based on the latest ideas in theology is precisely to put the cart before the horse, to found the law of worship on the law of belief.

When someone tries to clarify what we believe, that person is doing theology. Theology is one word that I’d like to focus a bit more on, since its meaning has drifted quite a bit. Another famous saying from the ancient church comes from the great monk Evagrius of Pontus. “He who prays is a theologian.” In the last century, Hans Urs von Balthasar gave renewed expression to this idea by urging that theology be done ‘on one’s knees’. I am grateful that von Balthasar (who was a scholar of Evagrius, among many other subjects), brought back the notion that perhaps theology is best practiced in the milieu of prayer rather than in the academy. Nevertheless, he misses an important part, I think. Really to pray requires that we have clear ideas of the God Whom we address (especially as we get older and face challenges to our faith; the prayer of a child can be very lovely and theological astute, as children tend to trust naturally, but as we age, we need to learn to pray as adults). From where comes these clear ideas? From the liturgy, Lex orandi lex credendi.

The decline of the liturgy in the West I would place in parallel to the rise of the philosophical ideas of voluntarist nominalism. I won’t try to demonstrate that here, since I’d like to wrap up for now. But one of the great insights of Laszlo Dobszay, the recently deceased dean of musical liturgists, makes this more plausible. Most people date the decline of liturgical observance to the reforms that followed Vatican II. Dobszay claims something else quite startling: that the reforms of Trent were already driven by a kind of expedience, by a centralized bureaucratic mindset that sensibly prevailed in the halls of the Roman curia, but was somewhat tone-deaf to the rich, local traditions that had been the warp and woof of liturgy since the Early Church. Thus the liturgy, as traditionally practiced, was already ceasing to make clear sense, even to sixteenth-century bishops. And this is, I would argue, because they were all formed, to a large extent, by the university system of the day, one that stressed voluntarism at the expense of a more integrated Thomism. I have to ask you to trust me on this one for now, and obviously I’ve got a bunch more posting to do to fill in the blanks.

My main point in this last paragraph is this: when we think of the decline of belief that has correlated with confusion in the liturgy since Vatican II, those who think that we’ve gone the wrong direction tend to look back to Trent for guidance. What if the Tridentine Fathers (affected by more than two centuries of nominalism) were already suffering from a slightly problematic understanding of the relationship between theology, prayer and liturgy? What if we need to return, not to 1950, but to 1150? Or 650? Obviously Benedictines will have a certain preference for the latter two years. Something to think about.

God’s blessings to you!

Prior Peter