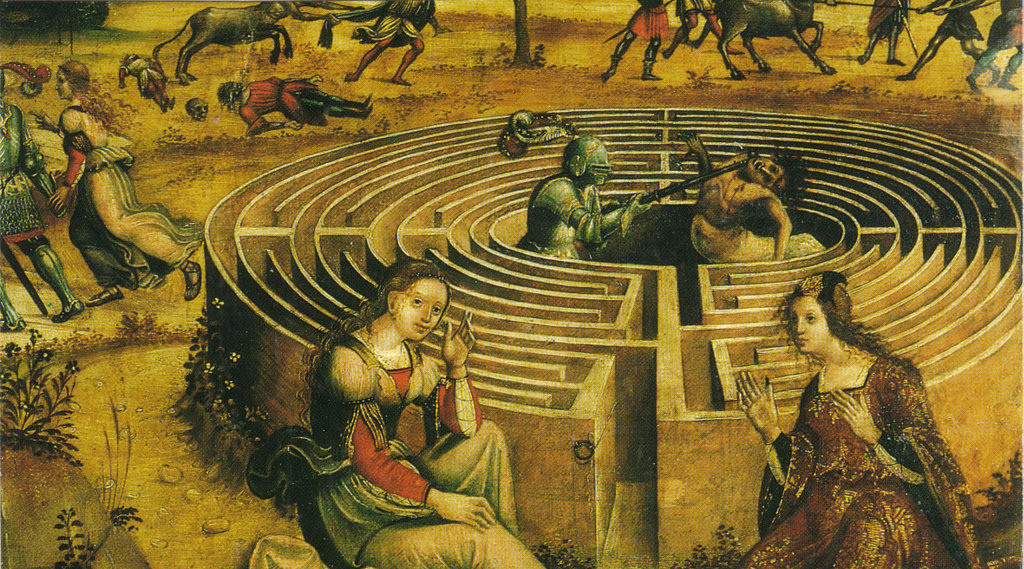

Thanks to Ariadne’s thread, Theseus was able to escape the labyrinth after slaying the Minotaur. In the Middle Ages, the Church saw Theseus as a type of Christ, descending into the dissolution of hell, slaying death, and leading the lost souls from darkness to light.

“[I]t’s time for the LGBT community to start moving beyond genetic predisposition as a tool for gaining mainstream acceptance of gay rights. . . .For decades now, it’s been the most powerful argument in the LGBT arsenal: that we were “born this way.” . . .Still, as compelling as these arguments are, they may have outgrown their usefulness”

I begin with a quote from dancer and writer Brandon Ambrosino, as quoted by Jonathan V. Last in the Weekly Standard. Last correctly points out the ‘bait and switch’ reasoning going on here. Genetic predisposition to homosexuality is, or was, presented as something true. When a proposition is true, it carries moral weight. True statements have a kind of prestige. But Mr. Ambrosino is admitting here that what was important was not whether homosexuality really, truly is a matter of genetic predisposition. What is important is that this claim turned out to be a “useful tool.” In other words, claiming this as a truth proved effective for one phase in the battle for mainstream acceptance of gay rights. Now that this goal is achieved, some other tool might be found lying about to serve the purposes of the next phase, whatever that should be.

I begin with this quote to illustrate a related point, a difficult sentence written by Alasdair MacIntyre in After Virtue. This routinely puzzles the novices in our community. It reads:

We should…consider whether [emotivism] ought not to have been proposed as a theory about the use–understood as purpose or function–of members of a certain class of expression rather than about their meaning.

MacIntyre claims that when our present society engages in moral discussion, it does so as an emotivist society. Emotivism tells us about the usefulness of moral expressions rather than assessing whether their meaning is true. This is exactly what Ambrosino is doing. It doesn’t matter whether it is true that same-sex attraction is rooted in genetics if the claim advances his personal aims. And according to MacIntyre, at the end of the day, this is what contemporary Americans do, advance personal aims by using expressions that sound like the truth.

In my experience, emotivism is one of the major problems today in monastic formation (and I dare say, catechetics in general). Here is a short description of what it is, from After Virtue.

In moral argument the apparent assertion of principles functions as a mask for expressions of personal preference.

Think talk radio and internet comment threads to get the idea.

We assert principles. We do this because, as I said about the truth above, principles have prestige. They are more persuasive than personal preferences. The problem arises when we can no longer agree on first principles. So how does one decide between competing and incompatible first principles? For example, how do I decide whether it is a first principle 1) that an unborn child is a human being and therefore protected by the right to life given in the Constitution, or 2) that women have the right to make decisions that affect their bodies, even to the extent of terminating a pregnancy when an embryo isn’t viable anyway? Defer for the moment the possibility of accepting certain arguments on authority, or suppose that our desire to accept arguments based on authority is itself a personal preference. In any case, we seem to have no way to decide rationally between first principles. And this has the unsettling effect of making our own moral convictions appear arbitrary. But we aren’t going to win anyone over my asserting our arbitrary convictions. So we resort to “the apparent assertion of principles,” but what we are really doing is arguing for personal preferences.

Obviously, if men enter a monastery with these hidden habits, many things will go wrong. And since emotivism is obscurantist (we ‘appear’ to assert principles in order to ‘mask’ our real intentions), it may take a while to uncover its manifestations. In any case, a life devoted to truth will require a radical change. So our men in formation are well versed in the problems of emotivism, and we work at strategies for conversion.

I will have more to say about the ruling of the Supreme Court today, and I will have a lot more to say about emotivism. Let me conclude this post with an important consequence of emotivism.

In an emotivist world, all relationships are manipulative

Even when I claim to be appealing to the truth, how do I know that I’m not using the label truth as a kind of bludgeon to force compliance with my personal preference? No one wants to be the rube opposing truth, especially in our world where one can be suddenly branded as a bigot or a terrorist sympathizer and be put out of work or exiled to Russia. But to make truth into a “tool” as Brandon Ambrosino admits he and others have done, is to admit that one doesn’t really believe in any truth at all. One simply puts forward as ‘truth’ whatever will be useful for manipulating others. Labeling something as ‘true’ turns out to be merely useful for gaining consent.

The terrible consequences of this habit of behavior are of several kinds. If we are used to being manipulated by persons claiming to know the truth, will we not eventually lose all confidence in authority? Will we not tend to assume that persons in authority, especially those with whom we disagree, are not merely using appeals to ‘truth’ to manipulate us for their own personal ends? Indeed, we see this correlated with a widespread loss of prestige for authority. If you are someone like me, who has been given a position of authority, a position I didn’t seek out, how do you teach the truth when audiences assume that you are out to manipulate them? This is especially difficult when, for example, the Church teaches something that happens to be unpopular with the particular congregation sitting in front of me. And in the end, how do I know whether my interpretations are really true or are merely personal preferences? Many, many Catholics perceive the teachings of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI and Pope Francis to be at odds. Isn’t this because we take as ‘true’ only those teachings of the Holy Father that we are already inclined to think are true? And we reject or relativize those teaching that don’t align with personal preference? For example, many of my conservative Catholic friends are certain that Laudato si, Pope Francis’s encyclical, is wrong on matters of economics, but these are almost all professional businessmen who have a vested interest in the status quo. This doesn’t mean that they are necessarily wrong, but it does lend to the impression that even Catholics, who are in theory committed to a whole host of first principles, still seem to pick and choose first principles somewhat arbitrarily.

There is a way out of this conundrum! Do not despair. But it may take us some time to walk back along Ariadne’s thread.