[Note: The following is the first entry in my new category of “jottings.” These are totally random observations based in my reading for larger projects. They will probably be, for the most part, either technical or expansively allusive in character and unapologetically so. Regular readers might choose to skip these, but they are intended to provide background for what I hope will be more popular writing in the main posts of this blog.]

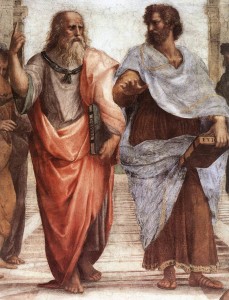

Studies in classical philosophy often contrast Plato with Aristotle. Raphael’s School of Athens shows Plato pointing up toward transcendent reality, the realm of the forms, more real than what senses can perceive. Aristotle, while not exactly pointing down, does appear to be tethering the conversation to what “common sense” can perceive of the only world that we can be confident of sharing with other rational beings. Students of these two philosophers often take sides, preferring one to the other, as though Plato’s greatest student, Aristotle, either refuted or strongly corrected his teacher, or, on the contrary, sadly eliminated all transcendent reference from the joy of philosophizing.

The truth is more complex. What I would like to note is that champions of Aristotle, who use the great man’s teachings against Plato and Socrates, surely do so unjustly. Let me focus on the figure of Socrates, as he is known to us from Plato’s writings about him. When Socrates came on the scene in Athens, he posed himself as an opponent of “common sense.” Yes. But why? I think there were two related reasons. First of all, he opposed a complacent, unexamined use of what passed as common knowledge. This was highly problematic in the quickly changing political atmosphere of his time. Outdated and worn-out ideas lazily copped from Homer’s two masterpieces, The Iliad and The Odyssey did not fit the reality of a budding urban empire.

Socrates also recognized that such complacency in the world of ideas left the people of Athens open to manipulation by demagogues. Such manipulation was openly practiced by the Sophists, the loose school of rhetoricians who “made the worse appear the better reason.” Now, so as not to be too hard on the Sophists, let us note that among the changes in Athenian culture from the heroic age of Homer to the progressive world of Socrates’s day, was a growth in the use of impersonal law to settle disputes. The problems with the legal culture will be a later target of Plato’s, in one of his non-Socratic dialogues. In Socrates’s immediate context, he saw that this reliance upon customary law was not conducive to any attempt to examine truth itself. Many of Plato’s dialogues rehearse Socrates’s method: pick a fight with a Sophist and demonstrate that the Sophist can’t produce a coherent explanation of the actual meaning of the words he is using. In other words, demonstrate that the Sophist tendency is to use words as tools for the achievement of personal goals by using them to manipulate his hearers.

Now let me note here that the theme of manipulation is of a piece with emotivism. Alasdair MacIntyre says that emotivism entails that there be no distinction between manipulative and non-manipulative relationships. That is to say, in our world, sophistry has returned largely unopposed, though we are not often aware of it.

Back to my narrative: Plato recorded and inherited Socrates’s technique and attempted to further the pursuit of truth in his own way. His painstaking accounts of the drama of Socrates’s life and the drama of Athenian society did much to clear away the fog of fuzzy, self-serving, manipulative reasoning. Perhaps he faltered a bit when trying to pin the idea of truth to the transcendent realm of forms. But his work made possible Aristotle’s astounding success in generating a durable realism, or at least something like a technique for separating specious claims about the world from more verifiable claims.

Thus began the arc of Western philosophy, and it apparently continued until the advent of Friedrich Nietzsche. He set the tone for the dismantling of Western philosophy with his remarkable work The Birth of Tragedy. Historians criticize his handling of materials, but he was astute enough to vilify Socrates and locate a turning point in Socrates’s Athens. In Nietzsche’s understanding, Socrates’s thirst for genuine truth was either pie-in-the-sky naivete or perhaps a cynical manipulation that claimed for itself the mantle of truth–which at least the Sophists generally had the good taste to avoid. For Nietzsche, Socrates inaugurated a long desert in which Western culture imagined itself bound by truth, but in fact deluded by this claim into a hideous blindness.

I believe that Nietzsche was perceptive in this claim, though not in the way that he intended. His “Hermeneutic of Suspicion” and “unmasking” of the hidden motives behind appeals to “truth” accurately described, not Western philosophy as such, but rather the particular situation of late nineteenth-century European academe. In other words, Nietzsche was, quite against his intentions, calling attention to the fact that European philosophy had fallen away from its traditional vocation of furthering the durable realism that the founders–Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle–had initiated. And desiring to call a spade a spade, Nietzsche proposed that we go back to acknowledging that rhetorical manipulations are all that we have.

As I suggested, my belief is that Nietzsche perceived that claims to truth by his contemporaries in philosophy really were infected with the complacency that Socrates opposed. How did this happen? It was a slow process, but my own biases lean toward pinpointing the nominalist revolution of the fourteenth century as the beginning. I would also note that this has its roots in the thinking of William of Ockham, who is generally considered to be one of the originators of nominalism. This was at a time when the connection between the liturgical life and the university life was considerably weakened. I don’t exactly like to blame William, since he inherited a number of tricky problems that resulted from institutionalized in-fighting between Dominicans and Franciscans in the early fourteenth-century university. But it does seem here that the first break between words and durable meaning is introduced.

It is worth noting that Pope Leo XIII seemed to have a similar intuition as Nietzsche, and perhaps a more accurate awareness of the reality of the breakdown in philosophy. In his encyclical Aeterni Patris, he insisted that seminary education return to Thomas Aquinas, two or more generations before Ockham. This set the stage for the amazing insights of the “New Theology” of the early twentieth century. Alas, just as we were reaping the fruits of this greater theological realism, seminary educators turned their back again on Thomas (who is regarded even by the non-theologically inclined, as one of the greatest, if not the greatest, of the interpreters of Aristotle). I am not advocating freezing philosophy in one thinker or time period; ironically what Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and Aquinas offer, if correctly understood, is not a complacent position of authoritative power, but a humble method for uprooting the false and lazy assumptions that steer us from the truth. And lazy thinking leaves us open yet again to manipulation by potentially unfriendly powers.