Lent begins today. We distributed ashes at Mass this morning. Shortly afterward, I distributed Lenten reading to each of the brothers. Saint Benedict instituted this practice in his Rule: the superior gives a book to each brother to be read straight through during Lent. I typically give each brother a classic from a Church Father or monastic saint, though occasionally, a brother might receive a book of more recent of theology if I think it might be useful.

At this point in my life I look forward to Lent with a kind of eager trepidation, if I can put it that way. When I was younger, it was a pure eagerness that accompanied this time of spiritual intensification. As I’ve gained experience, I know that, often enough, an unenlightened eagerness is the beginning of disappointment and recrimination. Therefore I now try to approach Lent with more wariness about the spiritual traps that inevitably accompany any effort to cooperate more fully with grace. The eagerness has in no way left me; it has been, I hope, tempered and made more realistic, more attuned to what spiritual warfare is actually like and to what my own temperament permits in the way of change.

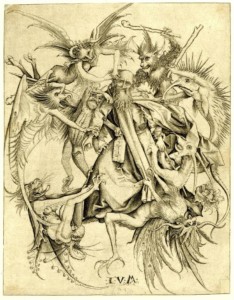

My favorite image of Saint Antony’s temptations, by Martin Schongauer. Two things to notice: the demons, externalized thoughts, are hard to distinguish from Antony. We often have difficulty separating from our thoughts, which is why slowing down and not reacting is so important. Secondly, Antony’s stoic resignation is part of the strategy. Rather than impulsively engaging the thoughts, he is simply allowing them to be, but staying mentally detached from them, not assenting, nor over-correcting by a fretful rejection of their presence.

It is often remarked that the word ‘joy’ appears twice in Saint Benedict’s chapter on Lent. This accords well with the Orthodox phrase “bright sadness” that is the desired disposition of the penitent in Great Lent. For this joy and bright sadness to accompany our fasting, it is important that we actually try to experience hunger. This means “moving toward” the perception of being hungry, accepting it without judgment as another experience. Can we sit still, when hungry, accept the lack of energy and the chills, without reacting? Am I inclined to give in to grumpiness? Or to think about how long it is until lunch? Or to complain about outdated, formalistic Church disciplines? Twenty years ago, our whole community experimented with a scientific, low-carb diet. I was impressed at the fact that balancing one’s carbohydrates with one’s proteins and fat intake makes it possible to lose weight without ever feeling very hungry. This would be another temptation against the fast, I think: seeing it merely in terms of eating healthier, losing weight, getting myself back into those pants that haven’t fit for the past few years or more. Weight loss and physical health are all good, to be sure, and we hope that they are results of the fast. But hunger, as we see in the temptation of Christ in the desert, is part of the process. I am hungry, but I accept that I am not going to eat right now.

We will discover, just as Jesus did, that other temptations dutifully follow after we have decisively, for the moment at least, said no to eating. When we are younger and perhaps less disciplined, the physical craving often remanifests itself laterally in the forms of a lustful eye, fantasizing, or seeking out energetic music or distracting entertainments. It would be useful to recognize this displacement and, as we had said no to eating, to say no to substitutes as well, especially the illicit ones. What we want is for the resistance to food to allow us to peer more deeply into the structure of our desires, especially those desires for safety, love, acceptance, power, and so on. A friend once told me that he stopped fasting because he discovered that it made him angry. My response to this is that fasting often reveals that I am an angry person, or at least a person who has habitually given myself over to anger. And I create an illusion of not being an angry person by cheerfully eating whenever something annoys me. So I never encounter the anger underneath the surface that drives my eating.

When anger, or sadness, or suspicion, or any other negative emotion arises, it is useful again to allow it to be, rather than pretending that it doesn’t exist. This also precludes giving in and treating anger or sadness as legitimate just because I happen to feel one of them at the moment. The point here is to avoid any “quick fix” by giving up the fast or by a superficial happy feeling that we achieve by rewatching an episode of Police Squad for the hundredth time. If I have made a vice of anger, I might need an occasional distraction like that to avoid losing my temper. But the eventual goal is simple and gentle detachment from the disturbance of anger and negativity. This will eventually allow me to confront the thoughts that drive the anger, thoughts of frustration with a brother or a spouse, fear about war in Ukraine (or Covid–remember those days?). From here I can gently substitute thoughts from Scripture, allowing the Holy Spirit to change my outlook gradually. What I discover at this stage are the ways in which I have bought into a narrative about the world, myself, and God, that is profoundly false and distorting–the serpent’s narrative. Holy reading allows me to enter into the truth about these things, a truth that brings an eventual sense of peace and trust.

Power is the deepest danger. Again, it is quite useful to sit still and tell myself, “I am hungry, and the lack of food means that I don’t have the energy to work as hard as usual.” Overwork and, more generally, overfunctioning, is a way of attempting to dominate my environment. In Saint Augustine’s famous and frightening phrase, it is the corrupting libido dominandi, the drive to dominate. When we get sick or injured, or when we are lethargic because of hunger, we lose a good amount of control over our circumstances. Again, this lack of control most often manifests first as anger or sadness. One benefit of being hungry is that anger and sadness are harder to maintain, and we are confronted eventually with our real powerlessness, the realization that our bodies one day (and every day one day sooner) will fall apart and die. “Remember that you are dust and to dust you shall return.”

At this point, we have little left but to turn to God, and this is undoubtedly the best place to be, because God really is in control of everything that matters in the end. “Submit to God. Resist the devil, and he will take flight. Draw close to God, and He will draw close to you [James 4: 7].” “Cast all your anxieties on Him, for he cares about you [1 Peter 5: 7].” This is the source of true joy and peace. As creatures of infinite desire, we find our rest in learning to desire the infinite God and His holy will. Recognizing all of the ways in which we settle for lesser goods is the source of compunction, a type of sadness. But it is a bright sadness because through it we are discovering the source and end of all spiritual longing, the love of the God of Jesus Christ.