Think for yourself!

By the time I was a highschooler, this mantra was assumed wisdom. The Vietnam War and Watergate had accelerated the questioning of authority. “Don’t trust anyone over thirty,” was quietly being replaced with, “Don’t trust any claim you can’t verify with your own eyes.” At least that was the ideal.

In such an environment, tradition often appeared to me as a surrender, a lazy forfeiting of one’s duty to discover the truth for oneself.

I began to think differently about tradition when I began my education as an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, where students go to grapple with Great Books. My first exposure to Plato and the Greek historian Thucydides demonstrated to me that others’ observations on the world might at times be superior to my own in their power to explain and organize experience. In many ways, Plato played a parallel role in my life to the role he played for St. Augustine, broadening my mind to a consideration of the non-material aspects of the world, to a critical engagement with what it means to think at all.

But the utility, and indeed, beauty of tradition really hit home in my studies of music. Under Bruce Tammen, I began to learn the craft of choral conducting. What constitutes a good vocal sound? The proper formation of a vowel and articulation of a consonant? How does the interpretation of Brahms differ from the interpretation of Rachmaninoff? Answers to these sorts of questions were inevitably personal. We would do things the way Robert Shaw did them, or based on Weston Noble’s experience. When question arose about the execution of Bach, Helmuth Rilling did the talking. These were three men under whom Bruce had sung. But their insights were also grounded in personal recollections of great figures of the previous generations, notably Toscanini in Shaw’s case. Similarly, when Bruce and I would discuss art song (especially French chansons), a passion that we share, standards were grounded in the advice and experiences of older contemporaries like Elly Ameling, Gérard Souzay and Dalton Baldwin, who in turn knew people who knew Fauré, Poulenc and others. Charles Rosen, a faculty member at the U of C until his recent death, has similar observations in his copious writings about piano performance, how his early study was grounded in the sensibilities and techniques of famous turn-of-the-century pianists, notably Josef Hofmann, who cribbed from Anton Rubenstein and Franz Liszt.

Then I began studying composition with Easley Blackwood. His way of speaking about right and wrong in composition was akin to Bruce’s reasoning when it came to choral and art song performance. Why treat variation on a theme in such-and-such a way? Because that’s what Tchaikovsky would have done, according to Nadia Boulanger, who had heard it from Stravinsky (Easley studied under Boulanger and Olivier Messaien in Paris). My first exercises were to write a few short piano pieces in the style of Chopin. I wasn’t allowed to get fancy yet. I had to change the way I wrote and heard music, in order to align my taste with that of established masters of the craft. And Easley would be the judge of whether I was succeeding.

Both of these experiences required me to become a different kind of person than I had been before exposure to this tradition-based manner of learning. In order to learn certain things, I had first to dispose myself to be able to have certain kinds of aesthetic experiences. This requires that one trust one’s teacher, and assume that the teacher has your good in mind rather than self-aggrandizement. One guarantee of the teacher’s purpose is his own deference to certified masters of the past, as well as the general recognition of the quality of his work in the present by other established master-craftsmen.

From this perspective, tradition no longer appears as an irrational block of customary observances that abrogate one’s critical faculties. In fact, a genuine grappling with tradition ought to sharpen one’s critical faculties by constantly calling out the narrowness of one’s own previous education, upbringing and exposure. Not everyone has the opportunity to enter into a truly critical engagement with a tradition like the Western classical music tradition, but even for the amateur, a willingness to trust the insights of such a tradition will make one more reasonable rather than less. And all traditions ought to function in this way.

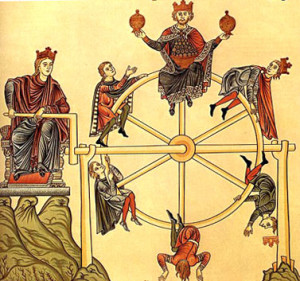

Human life being what it is, imperfect and prone to the fickleness of Lady Fortuna, traditions do get tangled, fall into dysfunction and disrepair and all the rest. But this is not a good reason to forswear all tradition. Yet it is one of the myths of the post-Enlightenment Western world that we should not ever trust traditions. Is it any wonder that we struggle to carry on anything like a rational debate in public life?

A corollary follows, with a stronger bearing on the purpose of this blog. Christianity, and within in it, monasticism, is a tradition. And to understand what the Church teaches requires from the disciple an act of faith that the Tradition and those charged with teaching it have the disciple’s good in mind. It also requires the disciple to become a different kind of person, which is to say, that we must undergo a conversion of life to enter more and more deeply into the truths that the Church means to convey to us. It will require us to leave behind the narrowness of our education, exposure and upbringing (especially that which took place “in the flesh”) so that we “may comprehend with all the saints what is the breadth and length and height and depth, and to know the love of Christ [Ephesians 3: 18].”

Update, July 28: It just happens that yesterday Classical Minnesota Public Radio did a big piece on Weston Noble, who, I realize, is not a household name outside of American Lutheran college choral aficionados. Here’s a link, if you are interested in learning more about him.