The Fourth of July is, hands down, the loudest day in our Bridgeport neighborhood. It’s always amusing when we have a new person in the community this time of year, impishly warning them what is coming: an hours-long, non-stop barrage of explosions coming from every conceivable direction. Many of our neighbors leave for a few days, especially those with dogs. We, too, used to find a refuge away from the city. Hours of explosions throughout the night is not conducive to a contemplative atmosphere, to say the least. We’ve learned to make peace with the situation by watching edifying movies into the night and having a sleep-in on the 5th.

I’ve even come to look forward to the way my neighbors celebrate American independence because it’s so clear that this holiday means a lot to them. From this perspective, our decision no longer to leave during the Fourth is a product of Benedictine stability. We monks actually make a vow to live in one place with the same community for the rest of our lives. This means that Benedictine monasteries are embedded very much in the local culture (paradoxically perhaps, we are also, by long custom and habit, close to the Church of Rome). This means that we share the joys and sorrows of our neighbors. We get to know families over many generations, and, one hopes, little by little a group of monks changes the culture around it by constant prayer, sacrifice, and love of God. Monasteries were the primary mechanism by which the continent of Europe gradually transformed from paganism to Christendom. This cannot be done when one doesn’t love one’s neighbors, one’s city and nation. Benedictines model this particular and local virtue of charity.

As I wrote some of the above lines in a recent thank-you letter, it sparked a larger thought regarding the Fourth of July. Patriotism has come to be seen by many contemporaries as the equivalent of a kind of bigoted nationalism. It supposedly encourages a myopia about the past sins of our fellow citizens and is therefore insensitive to those who suffered historical wrongs. In other words, patriotism involves a whitewashing of crimes and a narrow, even egotistical, pride in one’s nation.

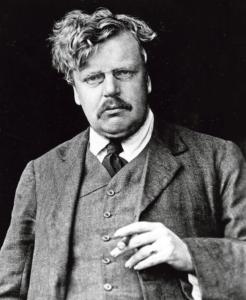

What we really need for the frustration and overthrow of a deaf and raucous Jingoism is a renascence of the love of the native land. When that comes, all shrill cries will cease suddenly. For the first of all the marks of love is seriousness: love will not accept sham bulletins or the empty victory of words. It will always esteem the most candid counsellor the best.

–G. K. Chesterton, “A Defense of Patriotism”

Activists who embrace this anti-patriotism seem never to be satisfied with any progress that is made to address historical wrongs. And this gives us a first clue as to what is wrong with this attitude from a Christian perspective. Saying that we shouldn’t love our country because it has been implicated in past sins is like saying that we shouldn’t love our parents unless they’ve led sinless lives. On the other hand, loving our parents does not mean thinking that our parents are better than someone else’s parents, any more than loving our country means thinking that our country is better than other countries. It simply doesn’t follow, even if some patriots really do believe this. I will go further. There might well be good reasons for thinking that one’s country possesses unique virtues in the global community. It’s possible, even likely!

The comparison between love of parents and love of country, while natural, is not one I can take the credit for. The connection is that of Saint Thomas Aquinas:

Man becomes a debtor to other men in various ways…man is debtor chiefly to his parents and his country, after God. Wherefore just as it belongs to religion to give worship to God, so does it belong to piety, in the second place, to give worship to one’s parents and one’s country…The worship given to our country includes homage to all our fellow-citizens and to all the friends of our country. [Summa Theologica II-II Q. 101 Art 2]

Thus, for Aquinas, patriotism is a Christian virtue.

There is one important thing to notice before I end this post. Aquinas does not vaunt any mystical “soul of the nation” or appeal to any kind of tribal blood relation. He is simply pointing out our debt to those with whom we immediately share life. This is why I made the connection with Benedictine stability, and why stability makes patriotism seem more obvious. David Goodhart has made a useful distinction between globalist “Anywheres” and the more rooted “Somewheres” in present political discussions. In the ancient world, rootless persons were non-persons. Empires forcibly resettled conquered persons to weaken them. Today, many of us see rootlessness as a desirable liberation. One wonders which vantage point is truer to human nature.

We wish you a safe and happy Fourth of July. May it bring about a greater desire to live the true Christian virtue of piety to our nation, and may the United States be a friend to other nations that we all may know something of the peace of God.