The Fourth of July is, hands down, the loudest day in our Bridgeport neighborhood. It’s always amusing when we have a new person in the community this time of year, impishly warning them what is coming: an hours-long, non-stop barrage of explosions coming from every conceivable direction. Many of our neighbors leave for a few days, especially those with dogs. We, too, used to find a refuge away from the city. Hours of explosions throughout the night is not conducive to a contemplative atmosphere, to say the least. We’ve learned to make peace with the situation by watching edifying movies into the night and having a sleep-in on the 5th.

Articles tagged with Aquinas

Can Faith Be Argued?

“We begin from faith, not reason. ‘Credo ut intelligam.’ But how does one argue faith?”

A friend recently asked me this question on a Facebook thread. The thread was about the degenerating relationship between the sexes, though the problem is clearly a more general one. That problem is one inherent in human nature and one that the institution of culture address: how do we resolve disagreements? I suspect that most of us, without reflecting on the problem, assume that we reason toward agreement. This would be terrific were it so; but this requires that we share premises and that we are skilled at drawing logical inferences from premises and applying them to particular cases. In other words, it requires that we be virtuous, using charity with our fellows and cultivating prudence.

Anxiety as Byproduct of the Rejection of Natural Law

Saturday, my host family took me to visit the town of Ely, which is near Cambridge where I’m enjoying a short sabbatical. Much of the medieval cathedral and its monastic buildings are still in existence. While I was there, the Worchester Cathedral Chamber Choir offered a short concert of pieces by Elgar, Handel, John Ireland, and others. Afterward, we all had tea. It was a splendid day.

Socrates vs. Nietzsche

[Note: The following is the first entry in my new category of “jottings.” These are totally random observations based in my reading for larger projects. They will probably be, for the most part, either technical or expansively allusive in character and unapologetically so. Regular readers might choose to skip these, but they are intended to provide background for what I hope will be more popular writing in the main posts of this blog.]

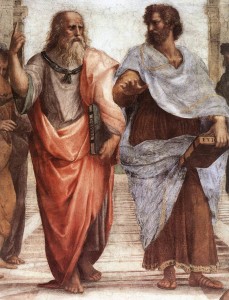

Studies in classical philosophy often contrast Plato with Aristotle. Raphael’s School of Athens shows Plato pointing up toward transcendent reality, the realm of the forms, more real than what senses can perceive. Aristotle, while not exactly pointing down, does appear to be tethering the conversation to what “common sense” can perceive of the only world that we can be confident of sharing with other rational beings. Students of these two philosophers often take sides, preferring one to the other, as though Plato’s greatest student, Aristotle, either refuted or strongly corrected his teacher, or, on the contrary, sadly eliminated all transcendent reference from the joy of philosophizing.

The truth is more complex. What I would like to note is that champions of Aristotle, who use the great man’s teachings against Plato and Socrates, surely do so unjustly. Let me focus on the figure of Socrates, as he is known to us from Plato’s writings about him. When Socrates came on the scene in Athens, he posed himself as an opponent of “common sense.” Yes. But why? I think there were two related reasons. First of all, he opposed a complacent, unexamined use of what passed as common knowledge. This was highly problematic in the quickly changing political atmosphere of his time. Outdated and worn-out ideas lazily copped from Homer’s two masterpieces, The Iliad and The Odyssey did not fit the reality of a budding urban empire.

Socrates also recognized that such complacency in the world of ideas left the people of Athens open to manipulation by demagogues. Such manipulation was openly practiced by the Sophists, the loose school of rhetoricians who “made the worse appear the better reason.” Now, so as not to be too hard on the Sophists, let us note that among the changes in Athenian culture from the heroic age of Homer to the progressive world of Socrates’s day, was a growth in the use of impersonal law to settle disputes. The problems with the legal culture will be a later target of Plato’s, in one of his non-Socratic dialogues. In Socrates’s immediate context, he saw that this reliance upon customary law was not conducive to any attempt to examine truth itself. Many of Plato’s dialogues rehearse Socrates’s method: pick a fight with a Sophist and demonstrate that the Sophist can’t produce a coherent explanation of the actual meaning of the words he is using. In other words, demonstrate that the Sophist tendency is to use words as tools for the achievement of personal goals by using them to manipulate his hearers.

Now let me note here that the theme of manipulation is of a piece with emotivism. Alasdair MacIntyre says that emotivism entails that there be no distinction between manipulative and non-manipulative relationships. That is to say, in our world, sophistry has returned largely unopposed, though we are not often aware of it.

Back to my narrative: Plato recorded and inherited Socrates’s technique and attempted to further the pursuit of truth in his own way. His painstaking accounts of the drama of Socrates’s life and the drama of Athenian society did much to clear away the fog of fuzzy, self-serving, manipulative reasoning. Perhaps he faltered a bit when trying to pin the idea of truth to the transcendent realm of forms. But his work made possible Aristotle’s astounding success in generating a durable realism, or at least something like a technique for separating specious claims about the world from more verifiable claims.

Thus began the arc of Western philosophy, and it apparently continued until the advent of Friedrich Nietzsche. He set the tone for the dismantling of Western philosophy with his remarkable work The Birth of Tragedy. Historians criticize his handling of materials, but he was astute enough to vilify Socrates and locate a turning point in Socrates’s Athens. In Nietzsche’s understanding, Socrates’s thirst for genuine truth was either pie-in-the-sky naivete or perhaps a cynical manipulation that claimed for itself the mantle of truth–which at least the Sophists generally had the good taste to avoid. For Nietzsche, Socrates inaugurated a long desert in which Western culture imagined itself bound by truth, but in fact deluded by this claim into a hideous blindness.

I believe that Nietzsche was perceptive in this claim, though not in the way that he intended. His “Hermeneutic of Suspicion” and “unmasking” of the hidden motives behind appeals to “truth” accurately described, not Western philosophy as such, but rather the particular situation of late nineteenth-century European academe. In other words, Nietzsche was, quite against his intentions, calling attention to the fact that European philosophy had fallen away from its traditional vocation of furthering the durable realism that the founders–Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle–had initiated. And desiring to call a spade a spade, Nietzsche proposed that we go back to acknowledging that rhetorical manipulations are all that we have.

As I suggested, my belief is that Nietzsche perceived that claims to truth by his contemporaries in philosophy really were infected with the complacency that Socrates opposed. How did this happen? It was a slow process, but my own biases lean toward pinpointing the nominalist revolution of the fourteenth century as the beginning. I would also note that this has its roots in the thinking of William of Ockham, who is generally considered to be one of the originators of nominalism. This was at a time when the connection between the liturgical life and the university life was considerably weakened. I don’t exactly like to blame William, since he inherited a number of tricky problems that resulted from institutionalized in-fighting between Dominicans and Franciscans in the early fourteenth-century university. But it does seem here that the first break between words and durable meaning is introduced.

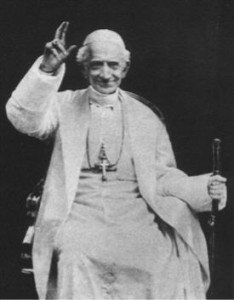

It is worth noting that Pope Leo XIII seemed to have a similar intuition as Nietzsche, and perhaps a more accurate awareness of the reality of the breakdown in philosophy. In his encyclical Aeterni Patris, he insisted that seminary education return to Thomas Aquinas, two or more generations before Ockham. This set the stage for the amazing insights of the “New Theology” of the early twentieth century. Alas, just as we were reaping the fruits of this greater theological realism, seminary educators turned their back again on Thomas (who is regarded even by the non-theologically inclined, as one of the greatest, if not the greatest, of the interpreters of Aristotle). I am not advocating freezing philosophy in one thinker or time period; ironically what Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and Aquinas offer, if correctly understood, is not a complacent position of authoritative power, but a humble method for uprooting the false and lazy assumptions that steer us from the truth. And lazy thinking leaves us open yet again to manipulation by potentially unfriendly powers.

Going to the Father 7: Icon and Altar as Ascension

The Ascension of Jesus Christ to the right hand of the Father is the founding moment of the liturgy. The Good Shepherd went off in search of His lost sheep–us–by laying aside His dignity and prerogatives as Son of God and becoming flesh for our sake. Becoming obedient to the Father even unto death, He won our salvation and returned to the Father as the pioneer of our salvation. In our baptisms, we are united with Christ, and in the liturgy, we participate, really experience our own ascensions to the Kingdom of Heaven, as daughters and sons of God in the Holy Spirit.

![Christ's Ascension is the founding movement of every liturgical celebration. Now He intercedes for us at the right hand of the Father [Romans 8: 34].](https://chicagomonk.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/ascension-coptic-215x300.jpg)

Christ’s Ascension is the founding movement of every liturgical celebration. Now He intercedes for us at the right hand of the Father [Romans 8: 34].

In Gothic church buildings, this symbolism of ascent is signified by the long “vertical” shape of the nave. One enters at the baptismal font, the gateway to life in Christ, and moves toward the altar through stages, not necessarily “closer to God,” Who is in any case not at all bound to the sanctuary, but through the purification of the soul, the understanding and the will, so as to be more and more conformed to God. Christ the Mediator is symbolized variously by the direction East (from whence He shall come at the parousia), the altar (incised with five crosses, the five wounds by which the risen Christ is recognized), the priest (whose initial movement to the altar is a representation of Christ’s Ascension), and finally by the Blessed Sacrament Itself.

Christ goes forth from the sanctuary at two crucial moments in the liturgy. The first is the gospel procession, where the Word becomes flesh, as it were, in the human voice of the priest of deacon who proclaims it. The gospel book is carried in procession from the altar to the people. The second movement “outward” is the carrying of the Body and Blood of Christ from the altar (again!) to the people, who now receive Christ Incarnate in Holy Communion. In this latter case, there is a complementary movement of the faithful toward the altar, “caught up together with [those who have died in Christ]…to meet the Lord [1 Thessalonians 4: 17].”

Christ in glory represents the Lord both ascending and returning (see Acts 1: 11). Note the two interlocking four-pointed stars and white rays, representing the divine energies radiating in and through the Son.

Here I am describing a dynamic liturgy, with a lot of movement. It is not what most Catholics think of when they think of liturgy, which unfortunately seems to bring to mind standing and sitting in one pew and watching while the priest does a bunch of things far away. What I have described is quite possible, even desirable in the present “ordinary” form of the Mass, and to a certain extent the reforms that followed Vatican II have made this latent dynamism more obvious (and this represents a restoration of certain elements of the Mass that had fallen away in the Tridentine period, which I personally consider to have been a bit ‘bureaucratized’, with a liturgy too much influenced by the Roman Curia and not enough by monks!). Orthodox liturgy tends to display this dynamism more openly, and often Orthodox liturgists will draw connections between the in-and-out motion of the priests and deacons with the mysterious energies of God, that go forth and return to Him [cf. Isaiah 55: 11]. And this connection in turn is sometimes reinforced with references to Eastern theologians like Gregory Palamas (1296-1359). But this dynamism is everywhere evident in Catholic sources, especially through the thirteenth century. The Summa Theologica of St. Thomas Aquinas is entirely patterned on what is called the “exitus-reditus” movement of God’s creative and restorative Word and Spirit, breathing outward into creation and gathering inward toward salvation and exaltation.

Our monastery church is a neo-gothic structure. The first altar that we had built for the church was slightly larger than four feet square and stood in the center of the sanctuary, at the eastern end of the building. Though it served us well, it was slightly small both for the space and for the number of concelebrants typical at our Eucharistic liturgy. After a benefactor came forward to commission the great iconostasis that you see on our home page (and above), we knew that it was time to commission as well a new altar. Present liturgical discipline favors a stone mensa or “table” on the altar. If we were to do have a stone altar constructed, we had two choices, necessitated by the weight of the potential structure. We could first of all restore it as a ‘high altar’ against the easternmost wall of the church. This would be easier and more cost effective, since there was already an iron and brick support in place there, and since we were already celebrating Mass ad orientem. The other option was keeping it in place and building a new support. This would have been quite costly. Moreover, the building itself calls for the altar to be at the very head of the structure, as the “Head” Who is Christ.

Our new iconostasis and altar, with four concelebrating priests. One gets a sense of the size of the church that we received from the Archdiocese and its orientation.

When the iconostasis and altar were installed last year (and I will have much more to write about the icons, so stay tuned!), the architecture of the church really came into strong focus. I can say with some assurance that all of the brothers have found this new arrangement to be a tremendous blessing and aid to prayer. The danger of such an arrangement is that the very strong vertical thrust might lead guests to feel faraway from the action and left out, as if God had retreated somewhere relatively inaccessible and only peeked out for communion. How could we help newcomers to feel more welcomed, to have a sense of God’s nearness without undoing the brilliance of the transcendent recaptured in our high altar and iconostasis? This was the challenge that we took up when we began to plan the last phase of our renovation of the church, the construction of the new choir.