I’m spending the week at my mother’s and stepfather’s farm, working on my book. I do hope to post somewhat regularly during this time, and continue to do so when I return.

I’ve written in the last two posts that our baptisms invite us to become different kinds of persons, not simply better persons, but truly different persons. Reborn persons. I also suggested that this process will keep us out of our comfort zones, that we can’t even be quite sure what kind of persons that God intends us to be, until we have developed the capacity to recognize what this otherness looks like and feels like. I finally suggested that if the liturgy disorients us, we should be cautious of “fixing” it by making it more rational.

This may sound like a recipe for complete nonsense. If we don’t know what kind of persons we are going to be until we get there, but we can only get there by being different kinds of persons, how can we proceed? One temptation in modern times is to understand the virtue of Faith as the engine that gets us where we are going. And faith in this sense is understood as a blind stab in the dark. God, in this model, takes pity on our helplessness and responds by mysteriously enlightening us.

This could happen. And it does. But it also is fraught with potential problems. I don’t find evidence of this dynamic in the early Church (with the possible and notable exception of Tertullian). Persons like Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria and Origen borrowed from themes in the writings of the Apostles John and Paul to stress the objective rationality of the Christian gospel over against the superstition of pagan piety. Pope Benedict XVI dwelt with this profoundly in his much-misunderstood Regensburg Address, titled “Three Stages in the Program of De-Hellenization.”

Furthermore, this is not a model that commends itself either to separated Protestant brethren or to most non-believers. From a Protestant perspective, the notion of blind faith might actually make sense, but then to make such an act of faith within the Catholic Church appears self-defeating. For critical thinkers outside Christianity, we would seem to be asking them to leave reason at the door.

Finally, such an act of blind faith contradicts the Magisterium, the teachings of the First Vatican Council and of Pope Saint John Paul II.

So what am I getting at? The paradox that I am describing was one recognized by Socrates. How can one discover justice when one is not just? The same way one learns to be a pianist without being born a pianist. One makes an act of faith in a teacher who already knows the craft, the kind of person that the student must become, and how to get train the student to become a real pianist.

Thus, if we are called to become eschatological persons, citizens of the Kingdom of God and fellow citizens with the saints, we must apprentice ourselves to those who already are the kinds of persons who know what this feels like. To some extent, this is all of us who attend the liturgy together, since at the liturgy we really are trained by the combined wisdom of a tradition molded by the experience of prayer and the presence of Christ.

Let me take this one step further, at some risk to myself. Even within the Church, there are those who spend more time and focus their lives more intently on living the life of the Kingdom now (or at least should be doing this). These are monks and nuns, especially of the contemplative type. This is why, historically, the liturgical books in the East have been crafted by monks, and in the West, up until around 1300 or so, the Benedictine Rite is almost indistinguishable from the Roman Rite in general. This is also why, after this link in the West was weakened, the liturgy has become shorter, and more ‘rational’ (meaning less mysterious and baffling). The changes that came after the Council were simply a continuation of a trend centuries in the making.

This is a shame because the Council’s teachings are actually quite lovely and traditionally orthodox. We as a Church were simply not prepared to implement them well in 1970. This has been changing. Our last three popes have all been profoundly shaped by the documents of Vatican II and have been finding creative ways to correct some misunderstandings. What I am thinking about here is how central the liturgy ought to be in our lives, for example. On the train up to Wisconsin on Sunday, I prayed the Roman Office from the community cellphone. It’s easy to find. Anyone can pray the Office, and many people are. The notes on the website were excellent. When I arrived, my stepfather shared with me his fondness for the publication This Day, which is Liturgical Press’s answer to the popular Magnificat publication. Both have shortened versions of Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer, based in the Psalms and the rest of Scripture, the daily readings from Mass, reflections on the saints in the calendar. These are beautiful examples not only of the centrality of the liturgy, but of the way in which the liturgy can connect to the increasingly important role of the laity to evangelize in the world. At the heart of our shared identity as the Body of Christ is our shared work of the liturgy, in which we see clearly how we relate as members of the Body, and we allow ourselves to be incorporated into this Body, lifted up with Christ to the right hand of the Father.

So…to wrap up:

Become a different kind of person, an eschatological person.

Live the Kingdom now, and train for this by praying the Church’s liturgy, even if on your smartphone in your room.

If monks and nuns require you to do strange things at the liturgy, don’t neglect them on the grounds that they are irrelevant rituals except to these strange contemplative types. We might not be able to explain right away why certain precepts need to be observed at the liturgy. You will get it once you’ve done it a bunch of times.

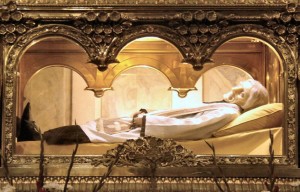

Imitate the lives of the saints. Of every era, not just recent ones or those who fit your definition of sanctity. Learn to be catholic in your tastes.

Never despair of God’s mercy.

“My little children, your hearts are small, but prayer stretches them and makes them capable of loving God. Through prayer we receive a foretaste of heaven and something of paradise comes down upon us.”–St. John Vianney