Mary, hearing the Word of God as spoken by Gabriel, said, “Yes,” and the result was the Incarnation of the Word within her. We participate in this mystical reality when, in our baptisms, we say, “I believe.” The life of Christ is conceived mystically in our hearts, and we are conceived in the womb of the Church. Like the life of an unborn child, our spiritual life needs the nourishment of the Church’s sacraments and teaching, so that we will eventually grow to maturity in faith. How does my life change when I truly and inwardly consent to the gift of faith? How do my actions change when I recognize the presence of Christ within?

Et Incarnatus Est – The Prior’s Blog

Incarnational Meditations on the Mysteries of the Rosary: Introduction

[Today I am embarking on what I hope will be a series of meditations on the mysteries of the rosary, from an ‘incarnational’ viewpoint. This first post will serve as an introduction to the series.]

What do I mean by an ‘incarnational’ meditation?

In fact, I mean to communicate several interlocking ideas, with the intention of countering a root difficulty in modern spirituality, our struggle with the concept of communion. We bristle—at some level, at least—at the notion of communion these days, whether it be with God or with the Church. There are many reasons for this. I suspect that a main problem is fear: fear that communion will mean losing ourselves, opening ourselves to ‘inauthenticity’ or, worse, being used by those who would claim to desire communion with us but in fact seek to dominate, to stamp out the uniqueness that each of us possesses by divine grace.

What does this leave us with, spiritually speaking? Well, there is a tendency to reduce Christian spirituality to a kind of ‘do-gooderism’, a series of ethical exhortations and practices and prayers. The purpose of these things—when they really do take place—is for God to communicate (just enough?) grace to allow us to do some good in the world, or at least be assured that we are not completely depraved.

Now, good works are not to be disparaged, and Christians are obliged to practice them. But we stumble when we notice that there are many persons in the world who achieve good works without being Christian. So if Christianity consists in showing that we are nicer and kinder than others, we founder on the empirical reality that this is, alas, often enough not the case. Here I should insert, in keeping with the overall goal of this proposed series of posts, that meditations on the mysteries of the rosary tend, in my experience, exactly toward an ethical model: we imitate Christ or Mary in order to become ‘better people’. This, in itself, has much to recommend it, but at some point this tack will, I believe, reveal its limitations in bringing us closer to the mystery of what it means to be Christian. What, then, does actually separate us as Christians from others in the world?

The answer is baptism: in baptism, we receive the very gift of God’s own life. In this communion of the divine and human in our own hearts, we recapitulate the reality of the Incarnation of God’s Word in the womb of the Virgin Mary, and indeed all the mysteries of the Life of Christ. We do not merely ‘imitate’, if we mean by this an effort (often conceived of as our own effort) to do things that we think Jesus would do. Imitation, in modern parlance, has something of a bad name. ‘Imitation’ wool or leather means ‘inauthentic’, a rip-off of something of superior quality. But when St. Paul exhorts us to “become imitators of me, as I am of Christ” [1 Cor 11: 1], we might hear that we are two steps down on the ladder of sanctity even before we begin. But Paul’s own imitation of Christ was so intense that he was able to become alter Christus, another Christ. Let me allow St. Gregory of Nyssa to emphasize this point for me:

“[Paul imitated Christ] so brilliantly that he revealed his own Master in himself, his own soul being transformed [my emphasis] through his accurate imitation of his prototype, so that Paul no longer seemed to be living and speaking, but Christ Himself seemed to be living in him. As this astute perceiver of particular goods says: ‘Do you seek a proof of the Christ who speaks in me?’ [2 Cor 13: 3] and: ‘It is now no longer I that live but Christ lives in me. [Gal. 2: 20]’”

—On Perfection, FOTC 58, trans. by Virginia Woods Callahan

What we have the privilege of being, already in this life, is the very Body of Christ alive and sanctifying the world. To do this, good works are necessary, but we also must be ‘renewed in mind’, not that we might be the only persons in the world who do good, but that we “may prove what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect.” [cf. Rom 12: 2] Being renewed in mind requires meditation, training the mind to see reality in a way different than we do by the sloth of habit. The Mysteries of the rosary have proven over many centuries to be a most efficacious means of meditation, especially for the laity. But meditate we must, not only on what we ought to do to improve ourselves with God’s grace, but to come to the understanding of the hidden growth of Christ within us. In living out the life of Christ in our imaginations, guided by the tutelage of His glorious Mother, the Virgin Mary, we attune ourselves to the quiet unfolding of grace in our lives, and are thus able to cooperate with grace more readily and gratefully. We no longer carry out good works to justify ourselves or salve troubled consciences, but truly as co-operators with Jesus Christ, alive in our hearts and present to the world in our actions.

Listening and Literacy

One of the techniques I like to use when teaching chant, especially complex chants that have many notes per syllable, is to simplify the chant by assigning one key note to each syllable, and then building up gradually to the full complement of notes. The advantage of this is the highlighting of the ornamental (i.e. non-melodic/structural) nature of Gregorian chant. This keeps things closer to the text and helps us work against the tendency to invest every note with a formal weight that the early monks clearly did not intend.

The disadvantage to this approach is that it requires the singers to put their books down and learn by listening and repetition. I say that this is a disadvantage because when I say to most people, “Alright, listen and repeat after me,” they are simply lost, no matter how simple (in my mind, at least) is the phrase that I am giving them. Yes, sometimes it is a problem of Latin; but from watching how people from all walks of life dearly resist putting down the book—the authority!—in order to enter into an oral mode of acting, I think that the problem is at least heightened by our emphasis on literacy. As I say, the book is the authority, and I am merely one interpreter, who obviously just learned this from the book.

Literacy is a great gift, of course, and allows us access to all kinds of cultural riches that are denied those who cannot read. But as we move further and further away from oral modes of learning and interacting, the disadvantages to a strictly text-based mode emerge. We can easily fool ourselves, by our reliance on texts, into thinking that we have learned something, when we have learned a simulacrum instead. We all know how a good professor can make a subject come alive; I’ve encountered persons recently who dismiss out of hand great philosophers simply on the basis of having read them and not liked them. There is no sense of the cultural embeddedness one needs to have to appreciate certain authors. This embeddedness is greatly enhanced by having it modeled by another human being. Someone who speaks passionately about Plato or Beethoven or Botticelli or the varieties of birdsong or human dialect can suddenly make an abstract idea one of real flesh and blood.

Literacy gives us the illusion of being self-sufficient, particularly as more and more texts become more available on the internet and elsewhere. Oral learning stresses our dependence on the experience of another.

In this way, the loss of music in school curricula is particularly to be lamented. My own love of oral/aural learning certainly comes from my musical background, which while literate, makes use of a lot of oral tradition. I learned German/American folk dances from simply playing along at family gatherings in my grandparents’ house. I learned guitar from friends (“Here is how you do the left hand for the opening chord in “Purple Haze”), and from listening to the radio and old vinyl albums. I played in a number of bands where learning a song meant sitting across from the songwriter, having him say, “OK, after that chord, this one for three beats, then a hit over here…” Even in classical music, I have long stressed the important sense of tradition that one must have. You can pick up a book of songs by Fauré and sing them correctly, note-for-note, and very easily miss the whole point of singing songs by Fauré. To really understand them requires some kind of mentorship, listening to a master sing and imitating what he or she is doing (in this case, Elly Ameling and Gérard Souzay, if you were wondering!).

This difficulty is an important one for us as Benedictines to be aware of. While we like to boast of the emphasis that Saint Benedict places on literacy in his Rule, we should always remember the word with which it opens: “Listen!”

Of Vacations and Vocations

At a discussion with university students and others this past Saturday, the young daughter of the man overseeing the event asked me if monks ever go on vacation. I answered, as I normally do, that, no, we are always monks even when we travel. We get this question frequently, normally from adults. Hearing the question from a youngster, however, brought out for me the inadequacy of my pat response. So, in the hopes that her father may share this more considered response, and that it may be of some use to others who may happen upon it, I set down here what I would have liked to have said to her then.

When your family goes on vacation, your father may be taking time away from work, and so is on vacation from his job. But he is not on vacation from being your father. In fact, he takes you and the whole family with him, and he serves you as a father wherever you go. And if he should have to travel without the family, it is not really a vacation because he is not with his family any more. Yet, as he is traveling, he is still your father, thinking about you, doing the things he needs to do to support you and the whole family. And he does this because he loves you, and your mother, and your brothers and sisters.

So it is that we never take a vacation from serving those whom we love. And so it is with the monk, whose love has been pledged to God instead of to a family. No matter where a monk travels, he does not take a vacation from serving God Whom he loves. If he has to travel somewhere in support of the monastery, to do business with worldly men and women for the sake of the monastery, he is still a monk, thinking about God, doing the things he needs to do to support his brothers who are also pledged to the love of God.

In fact, there is a kind of ongoing vacation that we all experience when we are together with those whom we love. The word “vacation” simply means “making space,” being free of manual work. The monk makes space for listening to God every day, as we should for those whom we love. When we love someone, we want to know how they feel, what happened in their day, and we want to share ourselves with them as well. As often as a family sits down to dinner and shares time together, they are sharing a miniature “vacation” (at least until it’s time to do dishes!). Everyone at the table is making time to be together and to relax a bit away from work. When we go away for vacation, this is to remind ourselves that we need this time each day, that our routine should never dull us to the great gift we have of each other, which often needs rediscovering. Now the monk, having been called out of the world to a life in solitude with God, is, in some ways, always on vacation, for he is striving to clear away as much as he can of anything that separates him from God. He is trying to make as much space in his day and in his heart as he can, for the Friend he is hoping to welcome, Whose voice he is seeking, exceeds all that we can love and desire. But, as I have already shared with you, I believe that family life has many of these same qualities, when we are striving to love one another. This is not always easy–believe me, I know this! But I also know that that love of our parents, sisters, and brothers is very much like the love of God–Jesus Himself said so! And so we are all, each in our own way, striving to grow in love by making space for others in our lives, and being welcomed by them into their hearts as well.

The Holy Triduum

We have arrived again at the holiest time of the Church’s Year, the annual celebration of the Paschal Mystery, our Lord’s Passover. It’s hard for me to believe that this will be my 27th Triduum at the monastery. The liturgy for this holy time can be bewildering when we first encounter it, but also exhilarating–and for the same reason. Everything is new, slightly disorienting. Time is suspended. Melodies and rituals suddenly appear that remind us of our first childhood memories of Easter.

Over time—and this is especially true for monks who must study the liturgy and practice it regularly—the ceremonies become more familiar, even if they remain special to this time of year. For some of us, there is a temptation to a bit of boredom—the old feelings no longer emerge with the same intensity. Every Triduum features a liturgical blunder or two–sometimes the same one many years running, and this can tempt us to cynicism. But these temptations should be dealt with in the same way that we deal with every temptation: with resistance. When we begin to understand the liturgy, not as a prompt for good and edifying feelings, appropriate as these might be, but as central to our permanent identity as children of God, we can transition into a deep sense of belonging to Jesus Christ and His Church. This identification and belonging will remain with us and inform the rest of our lives as Catholics throughout the year.

Once again, this applies especially to monks and nuns, who have espoused themselves to Christ. The transition of which I am speaking is analogous to one that we see in certain married couples. They begin their lives together with excitement, expectation, even a kind of infatuation with each other, and the joy of having been loved and accepted. There are new experiences of owning a home, of pregnancy, childbirth, school, in-laws, new family rituals at Christmas, and so on and so forth. This gives way eventually to routines, and as the new and exciting becomes the familiar and dull, there is a risk of each spouse focusing on the small annoyances of any relationship with inherently limited and even flawed persons. There are heartaches with children who suffer health problems, disappointments with careers and there are compromises. The temptation is to boredom and even a sense of resentment. But if this temptation is resisted, what emerges is the beauty of belonging to one’s spouse, of totally identifying with that person with whom I have made a lasting covenant, and struggled to live those vows in fidelity. These are the couples who can sit together for long periods of silence, simply content to be with their “better half,” appreciating the presence of the long-beloved.

The Holy Triduum is like the Church’s wedding anniversary, the annual reminder that we have been espoused by the great Bridegroom Who laid down His life for us, Who poured out His Blood to cleanse us and make the Church a worthy Bride for Himself, spotless and beautiful. When this reality is newly embraced, it can move us to great torrents of emotion. It can so move us even after many years. But it can also carry us away to a different kind of experience, that of profound and peaceful contemplation, the silent adoration of the Holy Trinity, to Whom be glory and honor forever. Amen.

The Mystery of Christmas

I have received many positive comments about the article that led our newsletter for Advent, so I would like to share it with a slightly different readership. I will preface this with a few more thoughts of Christmas, and why this celebration led me to my vocation. What gives coherence to the meaning of Christmas for me is the deep mystery of life itself. How is it that we–each of us a self, an “I”–observing the world and “All things counter, original, spare, strange; [Hopkins]” see things similarly, see things differently, see and understand anything at all? How often do we stop and wonder at it all? Something about Christmas always stopped me in my tracks and forced these questions upon me. The answer to this mystery is not the solution to a puzzle, but the sheer gift of love, of shared life and wonder. At the center of all that it, is a God Who wishes to be included in all things with us, our joys, sufferings, our boredom, weariness, excitement, community, loneliness, the whole labyrinth of life that each of us experiences. And in sharing the beauty of all that He created, He does so in most unprepossessing way possible, as a poor child of poor parents in a poor village, but rich in wonder and observation (read any of Christ’s parables and see how He never outgrew the child’s power of noticing things). We need not cross the sea to discover mystery–it is right in front of us and opens the way to participation in the Source of life.

[The article from our newsletter, entitled “Christmas and Everyday Life”]

One of the brothers recently asked me if there was a particular Christmas song that evoked strong memories for me. I couldn’t really answer the question because there are many such carols, in addition to the sublime arias and choruses of Handel’s Messiah and the magical dances of Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Nutcracker. I eventually settled on one carol, not because it is my favorite, but because it somehow summarizes the importance of Christmas to me: O Little Town of Bethlehem.

With a bit of imagination, the music of this lovely carol takes me back to decorating the house in preparation for the holidays. I always wanted to help set out the traditional nativity scene as well as the Christmas “village,” a tradition picked up from my father’s Polish family. We had pieced together this village over several years, and it included tiny houses, into the backs of which were inserted bulbs from strings of lights that would shine through the colored film windows. Miniature cars drove down snowy streets and sat in the parking lot next to the village church (which had a detachable steeple that occasionally was knocked over by our Labrador retriever). A mirror served as a skating rink, and a model train traversed the circumference of the town.

And of course, the were the tiny people there to celebrate winter by skating and skiing. In setting them up, we had to thread a tiny “rope” attached to a sled through the mittened hand of a bundled-up and straining adult. And then there were two blanketed children to be perched upon the sled. A thumb-sized collie ran alongside the family.

Perched behind all of this activity was, incongruously, the thatched barn giving shelter to the Christ child in the manger, adored by Mary and Joseph, and a motley band of shepherds. A variety of beasts kept the watch. To my eye, there was nothing quite as beautiful as these figurines, especially the shiny apparel of the Wise Men, the haughty camels, and the one poor shepherd, kneeling and offering a few coins resting in a cap in his hand.

Not only were these scenes separated by two millennia; they were not to scale. And yet, somehow, the ensemble spoke perfectly to me of the mystery of Christmas. The Son of God came, not only for the salvation of persons of the first century, but for every human being, for every human community. Not everyone in the Christmas village was in the church at that moment, but the church was there, its steeple pointing the way to heaven, or, in our humble tableau, to the angels singing above the newborn King.

Bethlehem was much like any other village, with its public spaces, rows of homes, families, children, pets, and other animals. When God sent His Son to redeem us, He came, not with spectacular show of “shock and awe,” but quietly, into a small home, beneath the same stars that we see today in the midnight sky. God thereby demonstrated that to be His child, it is enough to be human like anyone else.

The celebration of Christmas eventually had a profound effect on my own vocation. The beauty of God as a child, as an adolescent and young man, making friends, attending family weddings (I attended many weddings, as best man and as a musician)—the whole lot of everyday human life—made Christ especially present to me and made me want to respond by offering my life to Him as best I could, with the hope that perhaps others could experience what I had intuited: that into the darkness and obscurity of our quotidian existence, has shone the everlasting light. Now all the humble details of human life, the joy and tears, the sweat and rest, sowing and harvest, are illuminated from within by God’s Word. And that Word is Love.

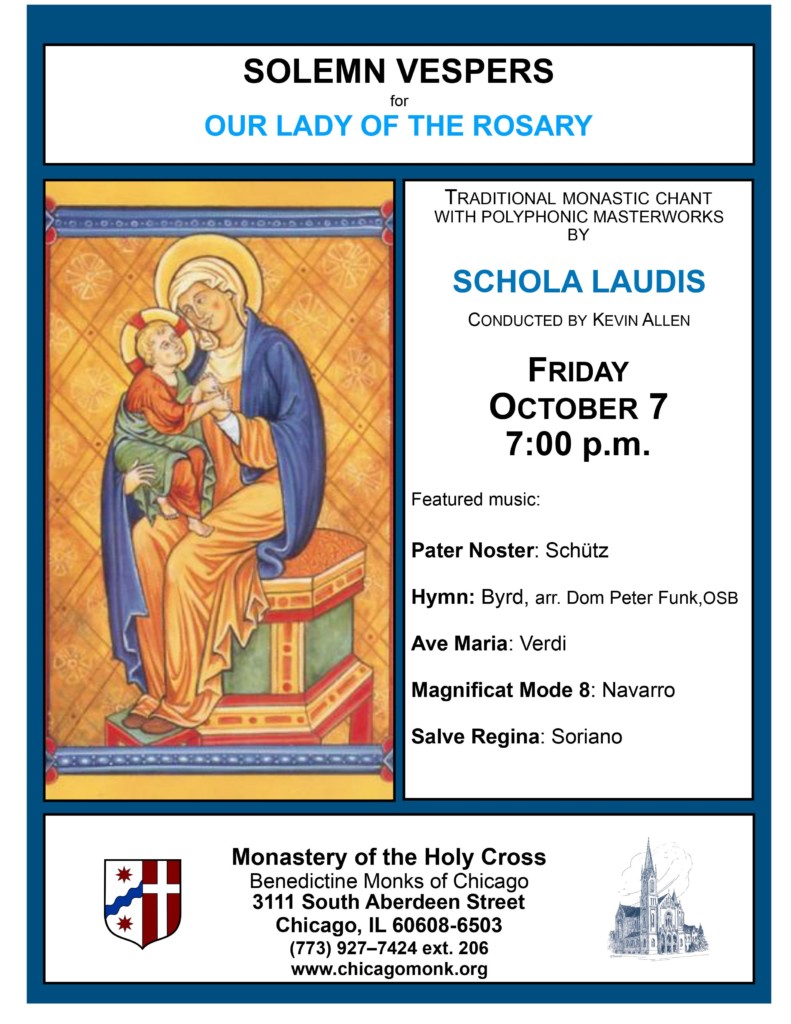

Our Lady of the Rosary

My mother taught me to pray the rosary. In her family, they had the old custom of praying a decade nightly on their knees, with my grandfather leading the prayer. While that lovely custom didn’t continue into my generation, the rosary continued to be the primary mode of prayer. It was definitely what we turned to when life became anxious for any reason.

The rosary developed over many centuries and through many twists and turns. The pious legend that Our Lady gave it directly to Saint Dominic has helped to cement the connection between the “Domini Canes” (the “hounds of the Lord” as the Dominicans have been playfully nicknamed) and Our Lady as the Vanquisher of All Heresies. The deep history is in the lay spirituality of the high medieval period, when lay brothers in monastic communities used beads to count 150 Paternosters in place of the 150 Psalms that were required weekly of the choir monks (who could read, and thus were expected to digest these extensive texts).

Eventually, these 150 beads came to represent 150 Ave Marias, and these were further divided into 15 decades, to which were assigned the familiar Joyful, Sorrowful, and Glorious Mysteries. Connecting the prayers to the Mysteries seems to have been another monastic innovation, this time from the Carthusian Dominic of Prussia. Confraternities of the rosary became popular in the late 15th and early 16th centuries.

But it was the clash of civilizations that culminated in the great Battle of Lepanto on October 7, 1571 that cemented today’s feast into the liturgy. As the Ottoman fleet prepared to square off against the Holy League of Catholic states, led by the soon-to-be famous Don John of Austria, Pope Saint Pius V urged all Catholics to pray the rosary in defense of Christendom, already tottering in the wake of the Reformation. The League’s decisive victory was attributed to Our Lady’s intercession, and effectively ended the Ottoman threat for another century and a half.

While the contemplative dimension has never been absent from the rosary, this more “militant” aspect also became more typical of the devotion. It is a part of spiritual warfare, as I discovered as a child, learning to ask Our Lady fervently for her protection under duress. The addition of the Fatima Prayer (…Lead all souls into heaven, especially those most in need of Thy mercy) strengthened the sense of prayer as battle. Pope Leo XIII, in his 1883 encyclical Supremi Apostolatus Officio, urged Catholics again to take up the rosary in battle, this time a more clearly spiritual battle than at Lepanto, against the incursions of particular evils into modern society.

More recently, Pope Saint John Paul II wrote his own apostolic letter, Rosarium Virginis Mariae, in which he extolled the contemplative dimensions of this devotion, even adding five new Luminous Mysteries. While I have heard some criticism of these additions (they disrupt the parallel between the 150 Ave Marias and Psalms), they are very much in line with another important document from his papacy, issued by the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. In this directory, pastors were urged to help the faithful to draw the connections between popular lay devotions and the liturgy. The 15 original Mysteries of the rosary corresponded to the most important mysteries of the Liturgical Year. John Paul’s introduction of the Luminous Mysteries fills out the traditional mysteries of Epiphany (adding the Baptism of Jesus and the Wedding at Cana), adds the central feast of the Transfiguration and the solemnity of Corpus Christi, and invites us to meditate on the feasts of the Apostles in the third of the Luminous Mysteries.

We happen to live in a most perplexing moment when, as in the times of Pius V and Leo XIII, the demonic spirit of deceit, division, and violence is visibly attacking the Church and humanity. In 2018, Pope Francis issued his own call to Catholics to engage anew the spiritual battle under the banner of the Virgin Mary, “asking the Holy Mother of God and Saint Michael Archangel to protect the Church from the devil, who always seeks to separate us from God and from each other.” It is not a coincidence that the rosary has recently been in the news, albeit with a certain amount of misinterpretation, as a symbol of (spiritual) militancy.

May our celebration this evening be pleasing to Almighty God, and may the Virgin Mother of God once again crush the head of the Serpent, that we may spend our days in peace and conversion of life. And may Christ lead us all to everlasting life. Amen.

Bright Sadness and the Joy of Spiritual Longing

Lent begins today. We distributed ashes at Mass this morning. Shortly afterward, I distributed Lenten reading to each of the brothers. Saint Benedict instituted this practice in his Rule: the superior gives a book to each brother to be read straight through during Lent. I typically give each brother a classic from a Church Father or monastic saint, though occasionally, a brother might receive a book of more recent of theology if I think it might be useful.

At this point in my life I look forward to Lent with a kind of eager trepidation, if I can put it that way. When I was younger, it was a pure eagerness that accompanied this time of spiritual intensification. As I’ve gained experience, I know that, often enough, an unenlightened eagerness is the beginning of disappointment and recrimination. Therefore I now try to approach Lent with more wariness about the spiritual traps that inevitably accompany any effort to cooperate more fully with grace. The eagerness has in no way left me; it has been, I hope, tempered and made more realistic, more attuned to what spiritual warfare is actually like and to what my own temperament permits in the way of change.

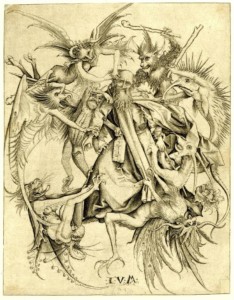

My favorite image of Saint Antony’s temptations, by Martin Schongauer. Two things to notice: the demons, externalized thoughts, are hard to distinguish from Antony. We often have difficulty separating from our thoughts, which is why slowing down and not reacting is so important. Secondly, Antony’s stoic resignation is part of the strategy. Rather than impulsively engaging the thoughts, he is simply allowing them to be, but staying mentally detached from them, not assenting, nor over-correcting by a fretful rejection of their presence.

It is often remarked that the word ‘joy’ appears twice in Saint Benedict’s chapter on Lent. This accords well with the Orthodox phrase “bright sadness” that is the desired disposition of the penitent in Great Lent. For this joy and bright sadness to accompany our fasting, it is important that we actually try to experience hunger. This means “moving toward” the perception of being hungry, accepting it without judgment as another experience. Can we sit still, when hungry, accept the lack of energy and the chills, without reacting? Am I inclined to give in to grumpiness? Or to think about how long it is until lunch? Or to complain about outdated, formalistic Church disciplines? Twenty years ago, our whole community experimented with a scientific, low-carb diet. I was impressed at the fact that balancing one’s carbohydrates with one’s proteins and fat intake makes it possible to lose weight without ever feeling very hungry. This would be another temptation against the fast, I think: seeing it merely in terms of eating healthier, losing weight, getting myself back into those pants that haven’t fit for the past few years or more. Weight loss and physical health are all good, to be sure, and we hope that they are results of the fast. But hunger, as we see in the temptation of Christ in the desert, is part of the process. I am hungry, but I accept that I am not going to eat right now.

We will discover, just as Jesus did, that other temptations dutifully follow after we have decisively, for the moment at least, said no to eating. When we are younger and perhaps less disciplined, the physical craving often remanifests itself laterally in the forms of a lustful eye, fantasizing, or seeking out energetic music or distracting entertainments. It would be useful to recognize this displacement and, as we had said no to eating, to say no to substitutes as well, especially the illicit ones. What we want is for the resistance to food to allow us to peer more deeply into the structure of our desires, especially those desires for safety, love, acceptance, power, and so on. A friend once told me that he stopped fasting because he discovered that it made him angry. My response to this is that fasting often reveals that I am an angry person, or at least a person who has habitually given myself over to anger. And I create an illusion of not being an angry person by cheerfully eating whenever something annoys me. So I never encounter the anger underneath the surface that drives my eating.

When anger, or sadness, or suspicion, or any other negative emotion arises, it is useful again to allow it to be, rather than pretending that it doesn’t exist. This also precludes giving in and treating anger or sadness as legitimate just because I happen to feel one of them at the moment. The point here is to avoid any “quick fix” by giving up the fast or by a superficial happy feeling that we achieve by rewatching an episode of Police Squad for the hundredth time. If I have made a vice of anger, I might need an occasional distraction like that to avoid losing my temper. But the eventual goal is simple and gentle detachment from the disturbance of anger and negativity. This will eventually allow me to confront the thoughts that drive the anger, thoughts of frustration with a brother or a spouse, fear about war in Ukraine (or Covid–remember those days?). From here I can gently substitute thoughts from Scripture, allowing the Holy Spirit to change my outlook gradually. What I discover at this stage are the ways in which I have bought into a narrative about the world, myself, and God, that is profoundly false and distorting–the serpent’s narrative. Holy reading allows me to enter into the truth about these things, a truth that brings an eventual sense of peace and trust.

Power is the deepest danger. Again, it is quite useful to sit still and tell myself, “I am hungry, and the lack of food means that I don’t have the energy to work as hard as usual.” Overwork and, more generally, overfunctioning, is a way of attempting to dominate my environment. In Saint Augustine’s famous and frightening phrase, it is the corrupting libido dominandi, the drive to dominate. When we get sick or injured, or when we are lethargic because of hunger, we lose a good amount of control over our circumstances. Again, this lack of control most often manifests first as anger or sadness. One benefit of being hungry is that anger and sadness are harder to maintain, and we are confronted eventually with our real powerlessness, the realization that our bodies one day (and every day one day sooner) will fall apart and die. “Remember that you are dust and to dust you shall return.”

At this point, we have little left but to turn to God, and this is undoubtedly the best place to be, because God really is in control of everything that matters in the end. “Submit to God. Resist the devil, and he will take flight. Draw close to God, and He will draw close to you [James 4: 7].” “Cast all your anxieties on Him, for he cares about you [1 Peter 5: 7].” This is the source of true joy and peace. As creatures of infinite desire, we find our rest in learning to desire the infinite God and His holy will. Recognizing all of the ways in which we settle for lesser goods is the source of compunction, a type of sadness. But it is a bright sadness because through it we are discovering the source and end of all spiritual longing, the love of the God of Jesus Christ.

Saint Scholastica: a model of prayer and charity

Today’s liturgical celebration, the feast of Saint Scholastica, holds an important place in Benedictine monasteries. Scholastica was Saint Benedict’s sister, and, according to Benedict’s biographer, Saint Gregory the Great, she was distinguished as having “greater love” than even our holy patriarch himself. It is a special day for all Benedictine sisters throughout the world—over 20,000 of them, in the “black” Benedictine federations alone—as we honor a woman whose prayer is known to be very powerful. (She once convinced God to send a thunderstorm when her brother was being slightly obstinate…)

In the Benedictine world, there is a sense that Benedict and Scholastica represent something like the “Petrine” and “Marian” aspects of the church as a whole. While the Petrine service of pastoring, legislative, and governing is extremely important (Benedict is often celebrated as our “Lawgiver”), the Marian service of the hidden life of prayer is the true heart of the Church’s secret fecundity. By prayer and contemplation, we open our hearts to experience God’s healing and loving presence within, and we open our minds to discover God’s sanctifying presence in all creation. A life of prayer truly puts God first, gives God the initiative (all prayer starts with the Holy Spirit!), and frees us from the burden of solving problems by our own powers.

The gospel for today’s feast, if you happen to be at Mass in a Benedictine monastery, is the famous passage about Mary and Martha. Our Lord gently chides Martha for being anxious about many things, and perhaps for being slightly annoyed with her sister Mary, sitting at the Lord’s feet and listening. It’s a shame that this story has come to represent the distinction between the active and contemplative life in religious orders. All of us need to be Marys at certain times, and Marthas at other times. But we should all seek to enshrine in our hearts the primacy of the “better part” of Mary.

I realize how difficult it is for many of us to get going on the life of prayer. Let me conclude by suggesting that it is a habit like any other habit. When you are trying to form a new habit, it is difficult and even painful at first, as we battle against other habits that need changing. Start small with prayer, and then try to expand from there. As you pray regularly, it will get easier, and as it does, it can be helpful to add a little more prayer. Soon, it will be a part of our day that we can’t do without. I was thinking this morning at lectio divina of the old saying of the virtuoso Vladimir Horowitz: “If I skip one day of practice, I notice; if I skip two, my friends notice; if I skip three, the audience notices.” I can tell when I have been lax at prayer for whatever reason, legitimate or not. My sense of God’s presence gets a bit opaque, and my sense of the sacredness of the people I meet becomes occluded. All it takes is to reengage with prayer, and these spiritual sense begin returning.

Gregory the Great tells us that Scholastica and Benedict used to spend days at a time discussing spiritual mysteries. How many of us could actually do such a thing for an hour, much less a whole day? Yet, I know from the great saints of the past and today’s spiritual masters that we can aspire to this spiritual fluency, but only if we pray.

Saint Scholastica, teach all of us, Benedictines and others, to pray as you prayed, that our souls may take flight and follow you on your heavenly journey to Christ!

What to do…

Amid much uncertainty in the world at the moment, we have gone about our monastic business quietly, praying for the nation, our city, the world. We’ve tried to keep our corner of the Bridgeport neighborhood, quiet, safe, and where possible, beautiful. Our garden has been quite fruitful, providing raspberries, blackberries, chard, beans, peppers, tomatoes. The deep green of trees gently waves outside my office window and elsewhere. The cats, domestic and stray, lounge about and are eager to eat when the food is brought out.

When we arrived thirty years ago, our properties featured a lot more concrete and less greenery. This meant, perhaps, less work cutting grass, weeding, and trimming trees. But the quiet reminder of God’s plentifulness that we see in the slow and sure maturation of the plants, fed by the rhythm of life-giving rain and sun, is worth a little extra work. So much anxiety comes of forgetting that reality does not depend on us. All that we receive in this world from God is a sign of His love and a pledge of the greater and permanent gifts He has promised. Are we watching for the clues He is leaving us each day?

I should add that I am in no way an isolationist or a fideist, advocating a willful ignorance of the challenges that we face at the moment, seemingly on all fronts. But in any action we might take to encourage one another, to right wrongs and seek justice, for this to be more than desperate bluster, we should want it to spring from an authentic encounter with Truth, Goodness, and Beauty. First of all, this will this mean that we are not reactively engaging out of pressurized fear and anxiety, but out of a sense of calling or vocation. This will help us avoid be manipulated by circumstances. We will tend to address problems that we know that we can solve, or at least ones to which we can offer competent pieces of a solution. But more importantly, we will be reminded of what the goal is. Like Sam Gamgee calling up sweet pictures of the Shire and Rosie Cotton amid the industrialized evil of Mordor, we will be fortified against bitterness and blind anger when our actions have the purpose of cooperating with, and restoring truth, goodness, and beauty.

More to come.