In the Catholic tradition, one composer stands above all the others in eminence for capturing the essence of liturgical music. This year, we celebrate the 500th anniversary of the birth of Giovanni Pierluigi di Palestrina (1525-1594), whose impact on both sacred and secular music in the West can hardly be calculated. On Saturday, October 18, at 5:15 p.m., here at the Monastery, we will be celebrating Solemn Vespers during which all of the choral compositions will be pieces by Palestrina. That we have such a selection of his music is itself an indication of his importance as a liturgical composer.

What is it about Palestrina’s art that stands above other Catholic composers? To answer this, it might help to take a step back and examine some theological questions.

The Christian faith is based in God’s self-revelation. However, God’s “unveiling” is always paradoxical. That is because no matter what we can say about God, there always remains an infinite amount that we do not yet know. All theology, if it is to avoid becoming something idolatrous, must bear this paradox in mind. Theologians must speak cautiously about the true and infinitely free “God-Who-Is” and not be satisfied with a lesser but more manageable god conjured up and constrained by logic and syllogisms.

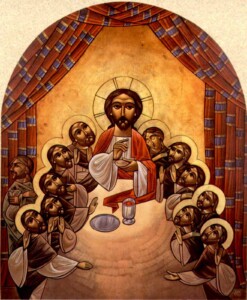

With this in mind, we can see how the Church’s liturgy is an important source for theological reflection. In the liturgy we hear Christ speak through the Scriptures and we experience His actions as members of His Body. The liturgy conveys something of the sovereign majesty of God as the One Who is always greater than what we can know. The Church has traditionally conveyed this excess of meaning through the liturgical arts.

For example, the liturgy takes place in buildings that convey mystical truths through architectural and ornamental symbols. Bishops, priests, and deacons wear elaborately decorated vestments that cloak their individuality and suggest other presences. Icons and statues convey their mysteries through the medium of visual art.

But the art that best symbolizes God’s mysterious presence is surely music. Music communicates the divine by being meaningful while nevertheless remaining opaque to verbal descriptions. Nothing I can tell you about a piece of music can take the place of you hearing it. And whatever meaning a piece of music has for me, any attempt to explain that meaning runs the risk of trivializing it.

Palestrina’s work has long been recognized as being particularly apt at finding this balance of intelligibility and mystery. His compositions have the power to move the emotions deeply without ever becoming sentimental, grotesque, or manipulative.

In the coming weeks, I plan to offer a series of blog posts discussing why I believe that the honors given to Palestrina are well-deserved. Hopefully readers will come to understand why he is considered one of the greatest composers of all time.

Since I have said that there is no verbal substitute for hearing an actual piece of music, we can hardly begin a commentary or exposition without some experience of what his music sounds like. Here is one of his most famous pieces, the Kyrie eleison of his Missa Papae Marcelli, the Mass for Pope Marcellus.

As we conclude this introductory post, keep these three things about Palestrina in mind…

The first is how his music flows without becoming nebulous. Palestrina was part of what was already a long tradition of liturgical composition. An earlier high point of this history sprang from the composers of the “low countries,” what we now call the Netherlands and Belgium. Composers like Adrian Willaert (ca. 1490-1562) aimed to offer us a taste of the vast angelic choirs through a technique called “seamless polyphony.” In my opinion, this is an extremely beautiful style. As implied by its name, the music flows seamlessly, without jarring transitions. The very lack of transitions can become its own problem, however. Liturgical music is based upon texts, which are broken into phrases and clauses, and Palestrina’s art honors this textual background especially well, balancing the need for transitions that are distinct yet never abrupt or jarring.

Second is the effortless beauty that suggests more than it says. As a general rule, Palestrina did not attempt to “interpret” the text by implying any kind of emotional affinity between the words and his musical setting. The approach that seeks to encode the music with an emotional or figural illustration of the words is sometimes known as “word painting.” It would be embraced by the great composers of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries like Handel and Bach. I will have a lot to say in later posts contrasting the genius of Bach and Palestrina. For now, let us just note that Palestrina, by avoiding any kind of interpretation, gives more of an impression that the music arises of its own accord, rather than being the product of a human mind. Word painting techniques can create a certain distractions by calling to mind the cleverness of the composer.

Third, whatever music you might need for any given liturgy, Palestrina has likely done a version of it. He lived right at the moment of the Counter-Reformation, when the Catholic Church was in the midst of sustained reflection on the meaning of the liturgy, which had come under attack from certain Protestant Reformers. Palestrina translated the musical principles of the Council of Trent (1545-1563) into an extremely fertile set of practices which became standard for Western music in general for the next four centuries. Every composer from Buxtehude to Brahms relied on the craft of Palestrina when honing his own techniques. Even today, when a composer wants to suggest the sacred, he will often rely on methods perfected by Palestrina and the generation of composers to which he belonged.

The heart of this technique was the way that composers handled dissonance, which will be the subject of the next post.

* “Rightly, then, the liturgy is considered as an exercise of the priestly office of Jesus Christ.”–Sacrosanctum concilium [the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy of Vatican II]