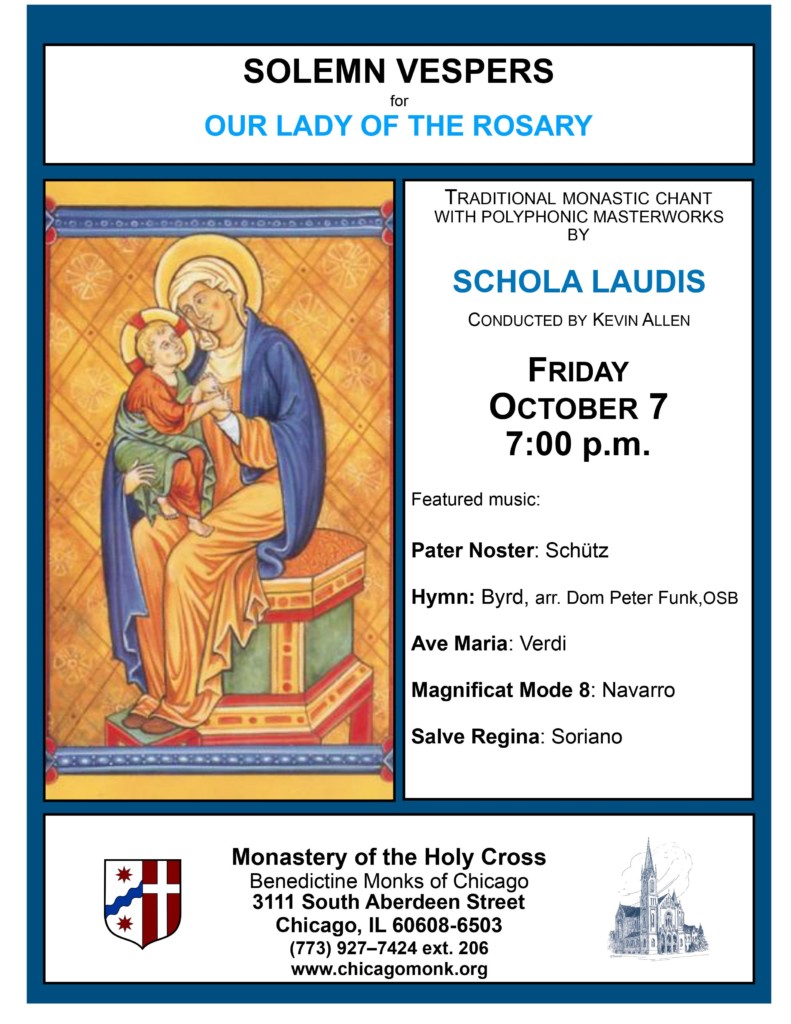

While doing a bit of searching in connection with yesterday’s Feast of the Holy Family, I discovered this striking–and humorous–image by the early 14th century Sienese iconographer Simoni Martini. It shows the finding of 12-year-old Jesus in the temple after Mary and Joseph had been searching for him for three days. Anyone who has parented an adolescent will, I hope, find this depiction amusing:

Let me take this opportunity to invite you to join us for Solemn Vespers tomorrow, Tuesday, December 31 at 5:15 p.m. In addition to exquisite music by Josquin and Willaert, our Schola will reprise a motet I composed for last year’s celebration: Virga Iesse floruit. At the bottom of this post is a sneak preview of the first of Josquin’s antiphon settings for this solemnity. The text, O admirabile commercium, with a translation, is also given below.

Merry Christmastide to all!

–Prior Peter, OSB

O admirabile commercium!

Creator generis humani,

animatum corpus sumens,

de Virgine nasci dignatus est:

et procedens homo sine semine,

largitus est nobis suam Deitatem.

O wondrous exchange:

the creator of human-kind,

taking on a living body

was worthy to be born of a virgin,

and, coming forth as a human without seed,

has given us his deity in abundance.