After a short hiatus to celebrate Thanksgiving (important, as we shall see), and to get Advent started, I’m back with more thoughts on American politics…from the vantage point of the cloister.

I asked in one of my earlier posts, “Will talking about the problem help?” Especially since the election, I have heard many Americans call for greater dialog between left and right. This seems like a plausible way forward. Surprisingly, perhaps, there are sociological reasons to be wary of whether increased talking can actually increase mutual understanding.

Let me begin with some anecdotal evidence of the hidden problem. About seven years ago, a high school friend, who has since become a proselytizing atheist, invited me to participate in an ongoing debate between Christians and atheists. The exercise was fascinating, if often extremely frustrating. The fascinating part was that no matter how much we talked, we managed agreement on only the most superficial matters. The reason? In order for either side to give an account of more important matters like politics, education, and morality, we necessarily had to bring in the fundamental disagreements. How should human biology be taught? Well, much depends on whether one has a fundamental commitment to the idea of the sanctity of human life, or if one leans toward a materialist belief that human and other animal life are more or less random assemblages of chemicals at this moment. There seems to be no way to judge which fundamental commitments are true.

At times, the superficial agreements acted as a kind of booby trap. My interest in music and in Nietzsche, for example, opened certain avenues of discussion that seemed fruitful at the start. But once we started to near bedrock again, and conflicts came out into the open, there was a strong temptation for one or both sides to accuse the other of deceit, of a set-up. “You only brought up music to trick me into becoming a Christian!”

This situation is evidence of a number of problems that can be characterized from a number of standpoints. For today, I want to focus on just one, the idea of “elaborated code.” Elaborated code is a term coined by sociologist Basil Bernstein. He studied the effect of industrialization in Great Britain in the 1960’s. Let me note right away that part of the trickle-down effect of industrialization is the breaking apart of older ways of social organization. Instead of visiting the cobbler to get shoes made, we now go to Target and buy shoes made in Taiwan. We don’t ever meet the shoemaker. He or she is not a part of our lives. Meanwhile, the old cobbler who is put out of a job making shoes now has to develop a very different set of skills to work in a factory or at Burger King. And, as we all know, job security in a globalized, industrialized economy is very weak. People change jobs regularly (another anecdote: I would estimate that about 2-3% of the persons on our list of donors change addresses each year). This constant shifting about calls for a mode of communication that is flexible and presumes that people don’t know each other very well.

Bernstein called this manner of communication elaborated code because of the frequent explanation and qualification required in this relatively new social situation. He contrasted this with “restricted code,” an unfortunate name for the kind of communication that takes place in a more stable environment. In a monastery, for example, there is relatively less need for frequent explanations of what I’m doing. But restricted code is more than just fewer words. It contains a much higher density of meaning, and restricted code often includes symbolic types of communication. For example, when a traditional family sits down to eat dinner together, it is not uncommon for the father to sit at the head of the table and the mother at the foot. Children are often arranged by age along the sides. This is a way of communicating certain roles within the family–without saying anything.

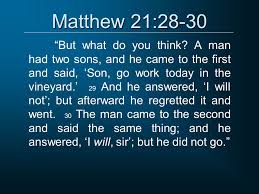

It’s interesting to note that young men entering monasteries today have very little experience of this kind of family setting, which was common in my home when I was a child. Let me give some other homely examples. When I would get into fights with my sisters, my mother would often admonish me with short sentences like, “You should know better. You are the oldest.” “Boys should never strike girls (this was not so easy for me to live by when my oldest sister would use her fingernails as a weapon; that wasn’t precisely allowed, but it had nothing like the stigma of me hitting my sister).” These short sentences communicate an entire world of values that we as a family were assumed to share. The sentences reinforced the importance of distinguishing between male and female roles, the responsibility assumed by elder siblings, and so on. This style of communication brings about agreement on social order at a very deep level.

And here is the important part: elaborated code not only presumes that we do not share agreement on social order, but that we will only be able to provide such order provisionally. The very mode of communication by elaborated code breaks apart shared agreement on social order, and trains us to “keep our options open.”

In the interest of keeping these posts relatively short, I won’t even hint at the way out of this dilemma, but I hope that it is clear that a greater sharing of ideas between left and right may not work as smoothly as we might hope. I will end by merely noting a further challenge. The political left is dominated today by persons who have been highly trained in elaborated code, not because of industrialization, but from indoctrination in the university system. This system itself has been powerfully shaped by the Prussian model of universities, a model explicitly crafted by the Prussian state to meet the needs of a newly industrialized world in the 19th century. This same model was loathed by none other than Friedrich Nietzsche. It is another sign of Nietzsche’s own insight that he withdrew from being a precocious university professor and busied himself with attempts to create a new mythology. In any case, it is not surprising that university education tends to fragment, rather than enhance, social coherence; that persons directly affected by the economic devastation wrought by globalization might be suspicious of the kind of fissile language that tends to pour forth from universities (e.g. identity politics, the recent creation of 47+ genders, etc). Economic hardship requires local cooperation, just the sort of thing enhanced by restricted code and blasted apart by elaborated code. So more talk may well have the unintended consequence of making community harder for just the persons that the political left needs to reach out to right now.

It is also no wonder that Trump supporters often cite his straight talk as a plus. I’m not sure that Trump merits that praise, but part of what is being communicated here is that Trump’s very style of speech is more closely related to the restricted code that is the glue that holds communities together.

If this isn’t your type of music, you can find the title of this post at 3:39 or so…