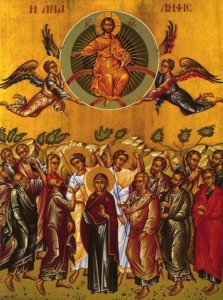

As the Catholic Church in the United States celebrates the solemnity of the Ascension today, I noticed that the reading assigned to the office of Vigils for this day, Ephesians 4: 1-22, clearly relates to themes I’ve been developing in recent posts. Today would be a good opportunity to look a bit deeper at the theological underpinnings of the following themes: 1) differentiation of responsibility in a healthy community; 2) that this differentiation promotes maturity, and 3) maturity is about rationality.

One preliminary point is of great importance: while the Church has traditionally separated the dates for the celebration of the Resurrection, Ascension, and Pentecost (the sending of the Holy Spirit), these should be understood as one Mystery. Thus, the Ascension is not only the enthronement of the risen Jesus at the right hand of God, it is also the birth of the Church (Christ’s resurrected Body, into which the baptized are incorporated). Liturgically, this birth of the Church is connected to the sending of the Holy Spirit, which Christ promised before His Ascension.

Paul, then, begins this meditation (which he writes from his jail cell in Rome), emphasizing the unity of the Church:

“I, then, a prisoner for the Lord, urge you to live in a manner worthy of the call you have received, with all humility and gentleness, with patience, bearing with one another through love, striving to preserve the unity of the spirit through the bond of peace: one body and one Spirit, as you were also called to the one hope of your call; one Lord, one faith, one baptism; one God and Father of all, who is over all and through all and in all.” [Ephesians 4: 1-6]

In our highly polarized environment, calls to unity are often heard as covert means of suppressing diversity. Indeed, one frequent criticism of Catholic Christianity targets the heavy freight of dogma to be taken on faith. This would seem to be the opposite of the rationality that I recently claimed comes from faith. From the standpoint of this criticism, faith would be submission to an authoritarian imposition of ideas and, therefore, a stifling of personal inquiry and questioning.

Thus, it is of some importance that Paul immediately switches to diversity within the Body:

But grace was given to each of us according to the measure of Christ’s gift. Therefore, it says:

“He ascended on high and took prisoners captive;

he gave gifts to men. [N.B. “gifts” in this context refers to the Holy Spirit]”…And he gave some as apostles, others as prophets, others as evangelists, others as pastors and teachers, to equip the holy ones for the work of ministry, for building up the body of Christ,” [vv. 7-8, 11-12]

Here we see the differentiation of responsibility. Not everyone is given responsibility for preaching or teaching. At Vatican II, this idea of Paul’s received a significant development. It was recognized that the Church, existing in the world, needs the expertise of lay persons who understand finance, law, medical ethics, economics, history, and so on. These can be seen genuinely as gifts from the Holy Spirit for the building up of the body of Christ. No longer does all of the responsibility fall on bishops and priests. Bishops need to consult with lay experts in a variety of fields precisely in order to hammer out theological positions.

From another perspective, dividing responsibility reduces anxiety and thus promotes mature reflection. The great sociologist, Mary Douglas, in her underappreciated book Natural Symbols makes this point from another perspective. She compares different types of community organization, and shows that small groups with a lack of differentiation of roles tend to suffer from fear of the world, witch hunts, and the like. By contrast, large, differentiated societies tend to promote intricately intertwined and symbolic understandings of the world. They tend to be quieter, more conducive to scientific and artistic achievements. This is not to say that they have no problems whatsoever. But it supports the overall principle that dividing up areas of responsibility reduces systemic anxiety. It also supports the notion that entry into the Church promotes rationality.

The next section of Ephesians amazes me:

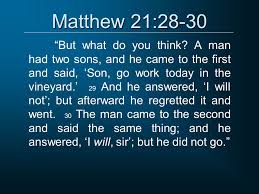

“until we all attain to the unity of faith and knowledge of the Son of God, to mature manhood, to the extent of the full stature of Christ, so that we may no longer be infants, tossed by waves and swept along by every wind of teaching arising from human trickery, from their cunning in the interests of deceitful scheming. Rather, living the truth in love, we should grow in every way into him who is the head, Christ, from whom the whole body, joined and held together by every supporting ligament, with the proper functioning of each part, brings about the body’s growth and builds itself up in love.” [vv. 13-16; my emphasis]

The unity of faith and knowledge is “of the Son of God,” Who is Truth. Since “all things came to be through Him [John 1: 3],” a true understanding of the cosmos opens up in the community of faith.

In other words, unity comes not from unthinking submission to dogmas imposed by authoritarian means. We all know, of course, that sometimes each of us must make an act of faith that an expert knows more than we do, and the expert can’t explain everything about a topic quickly. This act of faith presumes that what the expert knows is true, and that if we had enough time and training and facility, we would see the same truth as the expert, precisely because a mark of Truth is that it is the same for everyone. Thus unity arises from knowledge of the truth, and this acquired knowledge is a communal, cooperative affair. None of us is responsible for knowing everything. We must rely on “faith” that others will point us to truths that we cannot investigate entirely for ourselves.

Caravaggio’s depiction of Christ presented by Pilate. “Behold the man,” ironically points to the fulfillment of what God initiates in Genesis 1: 26. Whereas all other creatures spring to life when God says, “Let there be…” in the case of “man,” God says “Let us make man.” Here He is.

What is more, this faith and knowledge moves us toward maturity. “To mature manhood,” translates the Greek phrase, eis andra teleion. Knowing precisely what Paul means here is not easy because of the elasticity of the word andra, the dative form of the word for an adult man. We could, for example, translate this as “to mature adulthood.” However, it is also possible that andra is being used as a synonym for the more common Greek noun anthropos, which appears later in this same chapter, verses 23-24:

“be renewed in the spirit of your minds,and put on the new [man],* created in God’s way in righteousness and holiness of truth.”

This “new man” is Jesus Christ Himself, the goal [telos, from which we get teleion, or “matured”] of all creation. By our incorporation into His Body, we enter into that new society in which reason is allowed fully to flourish by faith.

It is of Christ that Pilate says, “Behold the man [anthropos]” just before His Crucifixion. In John’s Gospel, this is the hour in which all things are “finished” [tetelestai–from the same root as “mature” above]. It is also the moment at which Christ gives over the Spirit [John 19: 30].”**

Mature adulthood then, arises from our discovery of ourselves as members of a new community, rooted in Truth and Love. When we accept this new identity (the “new name” of Revelation 2: 17), and stay at our assigned posts, we can trust that God will mysteriously bring about the fulfillment of the resurrection by the renewal of our minds by the Truth. This will allow us to live authentically and avoid being taken in by human trickery–a valuable skill at any time, but perhaps especially in our present moment.

* The New American Bible Revised Edition unhelpfully translates this as “new self.” I’ve inserted “man” instead of “self,” for reasons that should be fairly clear.

** I am indebted to Fr. John Behr for this paragraph.