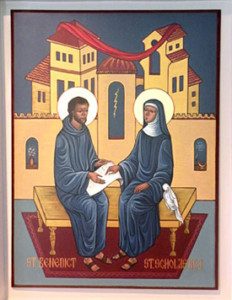

Today we conclude our annual retreat, and if you are thinking to yourself that we just did this a few months ago, you would be right. We have moved the time of our retreat back to February from November, where we observed it from 2018 until 2025. Today is an opportune day to end the retreat, since we have the custom of renewing our vows on the final day of the retreat. Today is the Feast of Saint Scholastica, the sister of Saint Benedict.

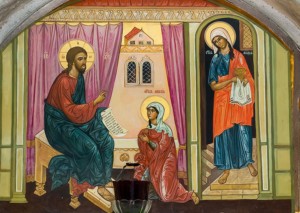

We know precious little of the life of Saint Scholastica, which was included by Saint Gregory the Great in his Dialogues, a book about the holy men and women of Italy of his time. We know that she had a convent near the great abbey of Monte Cassino, where he lived the last years of his life, and that she would go out of the convent annually to visit her saintly brother and discuss the joys of the spiritual life.

We know precious little of the life of Saint Scholastica, which was included by Saint Gregory the Great in his Dialogues, a book about the holy men and women of Italy of his time. We know that she had a convent near the great abbey of Monte Cassino, where he lived the last years of his life, and that she would go out of the convent annually to visit her saintly brother and discuss the joys of the spiritual life.

Gregory also tells us that her prayer was more powerful than her brother’s because she loved more. This should always be a burr in the saddle for the men’s branch of the Benedictines. Our order of monks has much to pride itself on: a 1500 year history during which hundreds and hundreds of monasteries helped to build up Europe, develop the Church’s liturgy, preserve the literary works of ancient Latin scholars, run the first schools for children, and on and on. In uncertain times like our own, there are many who look to monks for the “Benedict Option,” to renew this work of cultural preservation through the current Dark Age. If God wills it, may it be so.

But all of this work can miss the admonition of Saint Scholastica. At one point in the story of her last days, she says to Benedict, “I asked you and would not listen. I asked my God and He listened.” This a good-natured chiding, to be sure, but it contains a sharp point. Benedict begins his Rule with the word, “Listen,” and Saint Scholastica is suggesting to him that he isn’t living by his own teaching. He is forgetting what Saint Paul says in his First Letter to the Corinthians, as I would put it (if you will allow a paraphrase and a bit of hyperbole), “If I have the perfect observance of the monastic way of life, compose great works of theology, and preserve Western civilization, but have not love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal.”

So as we monks renew our solemn profession to continue in a life of obedience, stability and conversion of life, we should keep in mind Saint Scholastica’s challenge and example. May we do more—certainly! –not necessarily because we are strong or clever. In God, let us accomplish all that we do because we love.