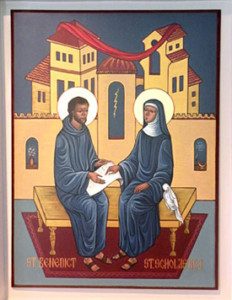

Today’s liturgical celebration, the feast of Saint Scholastica, holds an important place in Benedictine monasteries. Scholastica was Saint Benedict’s sister, and, according to Benedict’s biographer, Saint Gregory the Great, she was distinguished as having “greater love” than even our holy patriarch himself. It is a special day for all Benedictine sisters throughout the world—over 20,000 of them, in the “black” Benedictine federations alone—as we honor a woman whose prayer is known to be very powerful. (She once convinced God to send a thunderstorm when her brother was being slightly obstinate…)

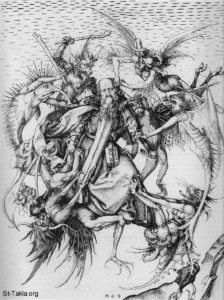

In the Benedictine world, there is a sense that Benedict and Scholastica represent something like the “Petrine” and “Marian” aspects of the church as a whole. While the Petrine service of pastoring, legislative, and governing is extremely important (Benedict is often celebrated as our “Lawgiver”), the Marian service of the hidden life of prayer is the true heart of the Church’s secret fecundity. By prayer and contemplation, we open our hearts to experience God’s healing and loving presence within, and we open our minds to discover God’s sanctifying presence in all creation. A life of prayer truly puts God first, gives God the initiative (all prayer starts with the Holy Spirit!), and frees us from the burden of solving problems by our own powers.

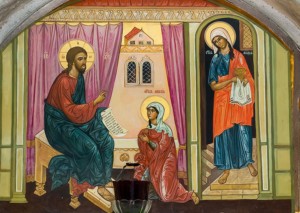

The gospel for today’s feast, if you happen to be at Mass in a Benedictine monastery, is the famous passage about Mary and Martha. Our Lord gently chides Martha for being anxious about many things, and perhaps for being slightly annoyed with her sister Mary, sitting at the Lord’s feet and listening. It’s a shame that this story has come to represent the distinction between the active and contemplative life in religious orders. All of us need to be Marys at certain times, and Marthas at other times. But we should all seek to enshrine in our hearts the primacy of the “better part” of Mary.

I realize how difficult it is for many of us to get going on the life of prayer. Let me conclude by suggesting that it is a habit like any other habit. When you are trying to form a new habit, it is difficult and even painful at first, as we battle against other habits that need changing. Start small with prayer, and then try to expand from there. As you pray regularly, it will get easier, and as it does, it can be helpful to add a little more prayer. Soon, it will be a part of our day that we can’t do without. I was thinking this morning at lectio divina of the old saying of the virtuoso Vladimir Horowitz: “If I skip one day of practice, I notice; if I skip two, my friends notice; if I skip three, the audience notices.” I can tell when I have been lax at prayer for whatever reason, legitimate or not. My sense of God’s presence gets a bit opaque, and my sense of the sacredness of the people I meet becomes occluded. All it takes is to reengage with prayer, and these spiritual sense begin returning.

Gregory the Great tells us that Scholastica and Benedict used to spend days at a time discussing spiritual mysteries. How many of us could actually do such a thing for an hour, much less a whole day? Yet, I know from the great saints of the past and today’s spiritual masters that we can aspire to this spiritual fluency, but only if we pray.

Saint Scholastica, teach all of us, Benedictines and others, to pray as you prayed, that our souls may take flight and follow you on your heavenly journey to Christ!