In the hands of a genius or a saint, or, even more so , a man who, like Bernard, is both, the artificial, the factitious, and art become natural, or, rather, nature yields itself unrestrainedly to art and its laws.

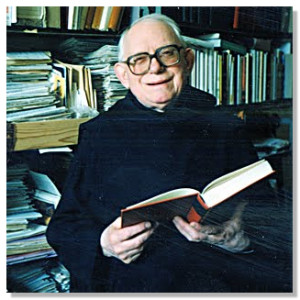

The specific type of cultural engagement of monasticism does not simply dissolve culture. It creates a new culture. Few have illustrated this with such erudition and passion as did Fr. Jean LeClercq, OSB. I opened with his description of the high art of St. Bernard’s prose and poetry. I struggled a bit to determine which book deserved first mention in this list of seminal works aimed at the renewal of the monastic mind, but in many ways, LeClercq set the standard. The title of his classic work, The Love of Learning and the Desire for God: A Study of Monastic Culture, says it all.

Among the key highlights:

1) Monastic renunciation of studies is not anti-intellectual but temporary, strategic, and prudential. St. Benedict famously fled from university studies in Rome because of the dangerous morals of the students there. According to Gregory the Great, he drew a connection between the subjects taught in the curriculum and the problematic behaviors he witnessed. So he withdrew to his cave at Subiaco to pray and begin a new life. But he did not forget all of his studies, nor did he forbid his eventual disciples study. In fact, in his Rule for Monks, he assigns the best parts of the day for monks to read, he insists that each monk be given a book to read during Lent, and he clearly wishes that public reading be taught and treasured (not an easy task in the days of handwritten manuscripts without spacing between words, capital letters, and punctuation).

And indeed, even the most grudging of historians today will acknowledge that few books in the West would have survived antiquity without the scriptoria of the great Benedictine monasteries. But reading and writing received their greatest impetus from the liturgy. Hence:

2) Monastic culture develops around the liturgy. Culture develops from the ‘cult’ of the liturgy. Celebration of the liturgy cultivates the new life in Christ. This should be said of all Christian life. But in the past millennium or so, even though in the West we pay lip service to the idea that the liturgy is the ‘source and summit’ of our life, it seems more frequently to be inserted instrumentally into an-already-in-progress life in the world, a helper and source of comfort, challenge and encouragement, but less often as the over-riding milieu in which all our thinking and acting takes place (according to the standard Patristic doctrine lex orandi lex credendi–the law of prayer determine the law of belief), and quite rarely as the summit of all our activity. This is a major theme that I hope to address in future posts. Simply raising this point, however, takes us to another central theme of LeClercq’s work.

3) Monastic culture is eschatological. When we step into the liturgy, we step into the end time. Monks aim to ‘eschatologize’ or ‘liturgize’ all of life. The whole cloister is arranged as if it is the restored garden of paradise. Monks cultivate a ‘devotion to heaven’, which is in fact a striving to instantiate the new heavens and new earth, to make the earth of our hearts receptive to the inbreaking kingdom.

Eschatology is not a word that we encounter frequently in contemporary Christian practice. What is it? It is the study of things of the ‘eschaton’, of the end time. What makes this interesting and energizing for traditional Christians (by this I mean mainly Catholic and Orthodox believers who have maintained the eschatological dimension of the liturgy) is that the end times have two aspects. In the one, it is that for which we hope, the revelation of the sons of God, the descent of the new heaven and new earth, the cosmos filled with knowledge of God like the water that covers the sea. It gives us a goal for our lives, a reason to keep the faith amid trials, a vision of what human beings will one day be. But there is more: we already live in the end times, and one key idea of eschatology is that we have access to it in the images of the liturgy, and to the extent that our imaginations are formed by the liturgy, by the spiritual interpretation of the Scriptures, we already peer into this blessed and joyous reality.

LeClercq and Thomas Merton were key figures in the recovery and editing of medieval monastic literature

We monks ought to make it our business to live in this reality as much as possible, and not for ourselves. The culture that the ‘monastic centuries’ cultivated inside the cloister became, in large part, the culture of medieval Europe. This is why Saint Benedict is the patron of Europe. If the Christian center of Europe has been fracturing over the centuries, it is, I believe, in part because the liturgy has informed culture less and less, and culture has instead begun to form (deform?) the liturgy. For this reason again, Benedictine withdrawal and liturgical practice and study is not at all at disengagement from culture, but a way to point the culture back to its roots, as much of it is redeemable.