In my “first thoughts,” I suggested that Christians interested in upholding the Church’s view of marriage might be better off letting go of a language of rights, since rights divide a coercive power from a class of victims. Turning this around we can also say that appealing to rights is a way of claiming the mantle of a victim and casting the Other as a victimizer. Either way, I think that it is clear that any sense of a genuine common good is undermined, subtly, by naked appeals to rights. Catholic social teaching depends on a clear sense of a common good, and a disciplined determination to live by it.

Here is where quite a bit of “Benedict Option” language also seems counterproductive, probably unintentionally. It sets the Opting party against the world. The language of separation tends toward a language of rejection. Now of course there are many attitudes in today’s dominant culture that a disciple of Jesus Christ must reject, and sometimes this rejection calls for disengagement from particular social structures. Repentance and conversion require new ways of living, and this means that behaviors must change. Conversion might require me to stop going to bars, or to movies, to the Freemason meetings, to my mistress’s apartment, and even to my place of employment. But the point of this is not to say, “Too bad for you, I’m outta here.” Rather, the penitent is aiming at identifying personal behaviors that are harmful and eliminating them.

If we actually believe in a common good, one of the best things that any one of us can do for others is to live a truly penitent and evangelical life. For when any one of us begins to live more vibrantly in Christ, all will benefit. Right?

And the inverse holds as well. When someone lives in contradiction to the truth, all suffer in some way.

Here is where I get to the Supreme Court ruling from three days ago. It is important to understand that what I am going to write needs to be read from a position of weakness (see my last post for an explanation).

This week’s Collect reads, in part:

grant, we pray,

that we may not be wrapped in the darkness of error

but always be seen to stand in the bright light of truth.

The bright light of truth! What a gift to know the Truth Who sets us free.

How deeply do we believe in the truth of the Church’s revelation? One of the dangerous habits of mind generated by our cultural emotivism is the assumption that any supposed statement of truth is in fact a statement of personal preference. From this perspective, all claims to truth are actually strategic claims, manipulating the hearer to feel obliged to accept what’s being stated. In other words, emotivism makes us all nihilists to some extent, perhaps a larger extent than we realize.

This conclusion, that many of us are closet nihilists, seems to me borne out by the fear, anger, and anxiety that I’ve encountered over the years when contemporary mores are discussed among Catholics. When, aided by the Church’s teaching, we identify actions as good or bad and we identify statements as true or false, how we happen to feel about the action or judgment makes no difference. Jesus Christ rose from the dead, and nothing changes about that if I happen to feel overjoyed about it or flatly unemotional. When we communicate the truth of the Faith, there is a tendency to add zest or urgency to our statements of truth by smiling, showing enthusiasm or worry or whatever. We act as if the Truth needs some goosing up, that it doesn’t stand on its own. But if the truth can’t stand on its own, it’s probably not true. [Digression: I personally see this as a weakness in the otherwise entertaining opinions penned by Justice Scalia.]

The other problem with emoting too much in discussions of truth is that the focus tends to be on ourselves and our feelings too much of the time. Thus many conservative responses to Obergefell v. Hodges that I’ve seen have focused on the dangers to Christians in the coming extension of the Culture War. Mind you, I think that these dangers are real, but again this reality isn’t going to be altered by me fulminating about it.

But the curious things about the Supreme Court ruling is this: if the resulting deformation of marriage really is about a false understanding of the nature of marriage, then the Court’s ruling will also harm precisely the persons that it is intended to help. This is just an inference from everything I’ve said so far. How will it hurt them? I have no clear idea at the moment. Nor do I wish to cook up a prophecy about what sort of harm is coming. But if this is true, then my concern should also be for my fellow Americans, providentially given to me by God for our mutual salvation, who embrace this new reality, even when they have the for the best possible intentions. Again, I would not attempt to walk up to a gay couple and baldly assert this and use it as grounds for them to renounce their marriage. I merely raise the issue to point out that it is possible to broaden our thinking about the situation in such a way as to keep from falling into the same adversarial stances that typify American public debates.

And even if it should come about that we suffer in some way for our beliefs, even this is more harmful, from the standpoint of faith, to the aggressor than to the victim. Here’s Saint John Chrysostom, the Golden-Tongued Wonder.

This is more than any one thing the cause of all our evils, that we do not so much as know at all who is the injured, and who the injurious person.

In focusing on the potential harm coming to those who oppose the redefinition of marriage, that is, to one segment of our world, we are liable to lose sight of the harm that we are all suffering together. Thus Pope Francis, “When our hearts are authentically open to universal communion, this sense of fraternity excludes nothing and no one.” [Laudato si, 92]

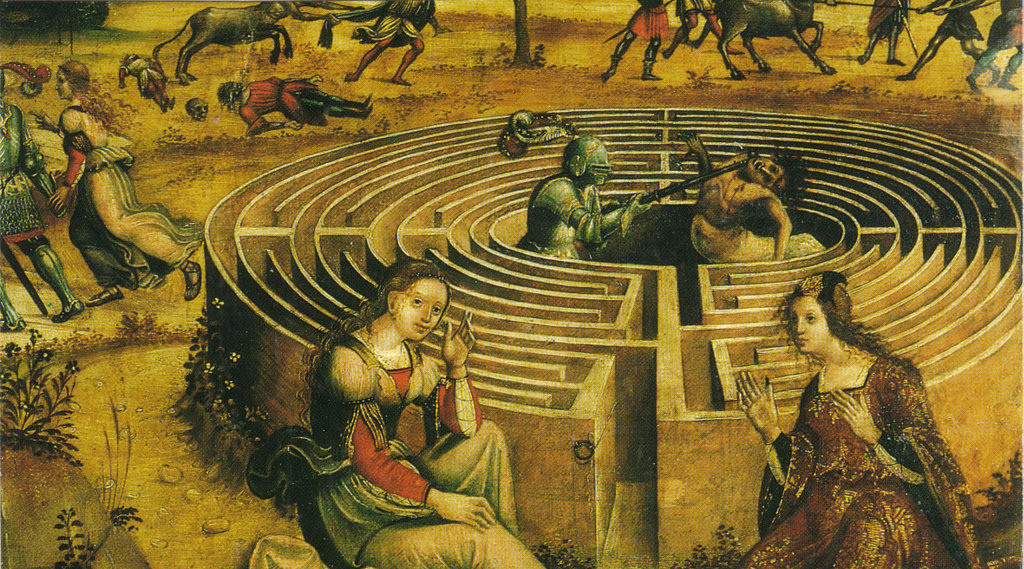

![Did you see some kid fall from the sky? Nah. [Bruegel the Elder's depiction of Icarus unmourned]--"Not an important failure," as told by Auden.](https://chicagomonk.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/icarus.jpg)