Amid much uncertainty in the world at the moment, we have gone about our monastic business quietly, praying for the nation, our city, the world. We’ve tried to keep our corner of the Bridgeport neighborhood, quiet, safe, and where possible, beautiful. Our garden has been quite fruitful, providing raspberries, blackberries, chard, beans, peppers, tomatoes. The deep green of trees gently waves outside my office window and elsewhere. The cats, domestic and stray, lounge about and are eager to eat when the food is brought out.

When we arrived thirty years ago, our properties featured a lot more concrete and less greenery. This meant, perhaps, less work cutting grass, weeding, and trimming trees. But the quiet reminder of God’s plentifulness that we see in the slow and sure maturation of the plants, fed by the rhythm of life-giving rain and sun, is worth a little extra work. So much anxiety comes of forgetting that reality does not depend on us. All that we receive in this world from God is a sign of His love and a pledge of the greater and permanent gifts He has promised. Are we watching for the clues He is leaving us each day?

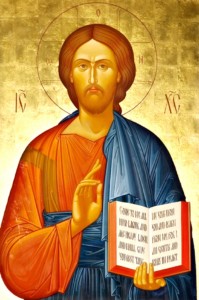

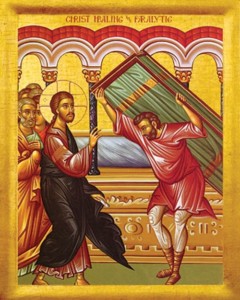

I should add that I am in no way an isolationist or a fideist, advocating a willful ignorance of the challenges that we face at the moment, seemingly on all fronts. But in any action we might take to encourage one another, to right wrongs and seek justice, for this to be more than desperate bluster, we should want it to spring from an authentic encounter with Truth, Goodness, and Beauty. First of all, this will this mean that we are not reactively engaging out of pressurized fear and anxiety, but out of a sense of calling or vocation. This will help us avoid be manipulated by circumstances. We will tend to address problems that we know that we can solve, or at least ones to which we can offer competent pieces of a solution. But more importantly, we will be reminded of what the goal is. Like Sam Gamgee calling up sweet pictures of the Shire and Rosie Cotton amid the industrialized evil of Mordor, we will be fortified against bitterness and blind anger when our actions have the purpose of cooperating with, and restoring truth, goodness, and beauty.

More to come.