We are preparing to have a new choir constructed and installed in our church. I have been invited by Fr. Anthony Ruff, OSB, at Pray Tell Blog, to offer some explanation of the theology behind the shape and placement of the choir. As a prelude to this project, and to give the fullest possible context, I would like to tell the story of our liturgical development, from the foundation of the monastery to the installation of the choir.

This story begins with our three founders working as missionaries in Haiti and Brazil

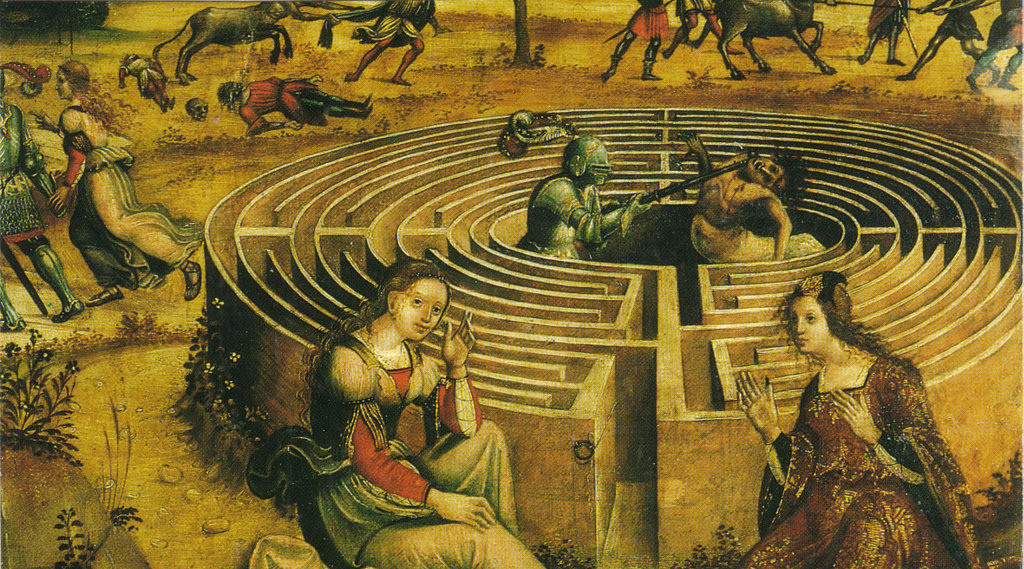

![Did you see some kid fall from the sky? Nah. [Bruegel the Elder's depiction of Icarus unmourned]--"Not an important failure," as told by Auden.](https://chicagomonk.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/icarus.jpg)