At one point in yesterday’s Oblate meeting, we discussed the difference between devotional pictures and icons. This discussion took place in a conference based on Pope Benedict XVI’s The Spirit of the Liturgy. And so it was noted that icons and devotional pictures might share themes, and composition. Pictures might even be of icons. But icons are always liturgical. The way an icon is prepared, the fasting that an iconographer undergoes, the forty days that an icon traditional rests upon a consecrated altar, and the final blessing of the icon by an ordained priest using holy water marks this object as part of the liturgy. A reproduction of an icon, such as those that adorn our home page, are not liturgical objects in this sense, but are devotional. As such, they extend from the liturgy and should lead us back to the liturgy. Reverence for an icon is a liturgical act, pious thoughts and prayer before a devotional picture is not–though these are perfectly good, even necessary, activities when one is not able to attend the liturgy itself.

I open with this reflection to draw attention to the breadth of what we mean by the liturgy. In the previous post, I noted that I needed to say something about what the liturgy is. I’ve spent a good amount of time explaining the liturgy’s interior, spiritual reality. From this vantage point, the liturgy is the work of Christ the high priest, bringing us to the Father in the Spirit, mediating for us and by means of us, His Body, for the salvation of the whole of the cosmos.

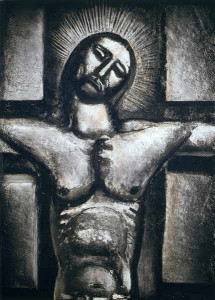

But how does this happen, and how do we know that it is happening? The liturgy also has an exterior, incarnated reality, in that it takes place by means of certain types of persons (the baptized generally, the ordained ministers in a more specific sense), at certain times, in certain places (mainly churches, but also anywhere that the faithful gather in Christ’s name), by means of certain texts and ritual actions, and with certain instruments (bread and wine, water, oil, stone, incense, vestments, icons, crosses, candlesticks, wax, etc.).

Catholics are apt to the of the Mass when someone says, “liturgy.” And this is a good impulse, though a truncated one. The liturgy’s center is indeed the Eucharist, but to reduce the liturgy to Mass is quite problematic. The liturgy includes all of the sacraments. It also includes the whole Divine Office. This is not an obligatory part of the liturgy for the laity. However, since it is the liturgy, the Divine Office possesses an efficacy for uniting us in spirit to God that non-liturgical prayer does not have (I plan to write about how to pray the rosary in a ‘liturgical’ manner, and why this is the deeper spirit of this beautiful–almost indispensable–devotional prayer).

But…I’m still not finished listing the events that make up the liturgy. Blessings pronounced by a priest are part of the liturgy, and blessed objects retain a connection to the liturgy. So what I said above about icons falls in here. So do meals (!). Exorcisms, processions, religious professions, oblations and promises are all part of the liturgy. The marriage act itself is liturgical, since it is intrinsic to the confection of the sacrament of matrimony (this is also why same-sex marriage, whatever merits there might be to bestowing recognition on a stable partnership of love, cannot be considered Christian marriage).

So the liturgy is actually quite extensive. In the West, we have had a tendency to shorten and narrow what we mean by the liturgy, as I mentioned above. This has some problematic effects. The good news, however, is that recovering the richness of the liturgy can be a life-altering project, a real point of foundational renewal for the Church, and the basis any genuine ecumenical effort. As I mentioned in the last post, the corporal works of mercy are not therefore dispensable. They will be efficacious, I would suggest, to the extent that those ministering in this way are clearly grounded in the liturgy. The acts of healing and love, the active life, will be seen to be the work of Christ Himself and not simply that of human do-gooders. In fact, we can throw ourselves into all kinds of activities, without fear of falling into Pelagianism, if our source of energy and strength is Christ Himself, uniting us to Him and to each other in the liturgy, He “Who has made the two one.”

From this standpoint again, we have a way of understanding the Church’s traditional teaching on the centrality of the consecrated life, especially the contemplative life. Contemplatives have the duty to live the liturgical life to the fullest, to invite others to the vision of the liturgy, and to give witness to Christ’s triumph and mission of reconciliation. “A monk is he who directs his gaze towards God alone, and who, being at peace with God, becomes a source of peace,” said St. Theodore the Studite. Christ made peace by the blood of His Cross [Colossians 1: 20], that is, by the unique sacrifice which is extended and re-presented at every liturgical event. And immersion in this reality changes us into eschatological persons.

Mass is often seen merely as an obligation, and the notion that even the laity would benefit from regular attendance at yet more of the liturgy is, in my experience, often shrugged off as an inconvenience, taking them away from more pressing concerns. From the perspective that I am outlining here, I hope that it is clear that this dismissal is skewed somewhat. Yes, Mass is obligatory for a baptized Catholic, but if we knew the gift of God that is the liturgy, we would welcome opportunities to participate more frequently, as our state in life permits. We would also learn to connect all of our prayer to the liturgical celebrations, to the vocabulary, priorities, and sentiments of the “work of God.” Then all of our prayer would be transforming us into women and men of Christ, into saints. Thus it is that the liturgy is the foundation for one of the most crucial insights of Vatican II, the universal call to holiness.