Tonight, we begin our fourteenth season of Solemn Vespers at 5:15 p.m. Here are my program notes:

“If you want peace, work for justice.”

This was the title of an address given by Pope Saint Paul VI at the Vatican on the World Day for Peace in 1972. The backdrop for this address was the Vietnam War and the Cold War. The United States had been undergoing unrest internally, with radical groups carrying out bombings and assassinations. It made sense to examine the idea of peace and to discover the means to obtain it. It makes sense for us to do so right now.

In his address, the Holy Father was at pains to make sure that peace is correctly understood. It is not something that arises spontaneously. It requires effort and vigilance, and right relationships between people and nations. These right relationships make up what the Catholic tradition calls justice. Saint Augustine defined peace as tranquillitas ordinis, the tranquility that arises from a well-ordered society. Our efforts to make the world more just will increase the likelihood of a peaceful world. By contrast, injustice breeds discord, resentment, and, eventually, violence.

There is one additional factor that the pope knew well, though he did not make it explicit in his address. In this world, peace cannot be fully attained by mere human effort and good will. The years after the Second Vatican Council fostered a kind of humanist optimism that unfortunately overshadowed the reality that our world is fallen. This unsettling fact does not mean that we are completely helpless to achieve peace, however. The New Testament offers a different way:

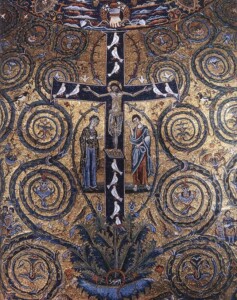

“For in [Jesus Christ] all the fulness of God was pleased to dwell, and through him to reconcile to himself all things…making peace by the blood of his Cross [Colossians 1: 19-20].”

“For he is our peace, who has made us both one…that he might create in himself one new man in place of the two, so making peace, and might reconcile us to God in one body through the Cross [Ephesians 2: 14-16].”

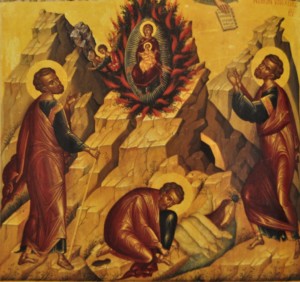

In other words, true and enduring peace is possible because of the rescue mission of the Son of God. He was sent by the Father to become incarnate in our human flesh. That very flesh was to be nailed a Cross, to suffer the gravest injustice one can imagine. Is there a better illustration of man’s inability to attain peace by his own powers? When presented with the one innocent man in history, we violently put an end to His life…by judicial murder!

Through the Holy Cross, Jesus gives us the gift of peace. To expand the thought of Saint Paul VI, we might say, “If you want justice, receive first the peace of Christ.” This is a peace from a different place: “Not as the world gives do I give peace [cf. John 14: 27].” All worldly peace is a (pale) reflection of the “peace of God which passes all understanding [Philippians 4: 7].” And there is no way to arrive at this peace that bypasses the Holy Cross, whose triumph we celebrate tonight.

Through the Holy Cross, Jesus gives us the gift of peace. To expand the thought of Saint Paul VI, we might say, “If you want justice, receive first the peace of Christ.” This is a peace from a different place: “Not as the world gives do I give peace [cf. John 14: 27].” All worldly peace is a (pale) reflection of the “peace of God which passes all understanding [Philippians 4: 7].” And there is no way to arrive at this peace that bypasses the Holy Cross, whose triumph we celebrate tonight.

It is significant that the evangelists Luke and John record Jesus, after the Resurrection, greeting His Apostles with the words, “Peace be with you.” To my knowledge, Jesus does not use this greeting before His death. The peace that Jesus gives, He gives because He has already reconciled us to each other and to the Father.

There is one more connection worth noting, this time between justice and the Cross. In tonight’s responsory, we will sing, “The sign of the Cross will appear in heaven when God comes to judge.” Thus, the definitive establishment of justice will happen at the judgment, under the sign of the Cross. The barbaric symbol of man’s injustice will be transformed into a sign of God’s love and Christ’s triumph. The Cross has become our standard, under which we fight against the injustices in the world.

Will we accept this gift of peace along with the Cross and its inverted triumph? That is a question that we Christians should always be asking ourselves, especially in our tumultuous times. If we fail to do this, we will be unwitting conspirators with the forces that would usher in an era of enforced, false peace (which is in fact fearful silence) by means of violence and the threat of violence. As we celebrate Christ’s victory tonight, let us earnestly entreat God to renew in us a commitment to “seek peace and pursue it [Psalm 34: 14]!” Let us take up our share in the Cross of Christ that we may one day share in His triumph.