In 2001, the Congregation for Divine Worship put out an important document, the Directory on Popular Piety and the Liturgy. Paragraph 5 of this important document is worth quoting at length:

The correct relationship between these two expressions of faith must be based on certain firm principles, the first of which recognises that the Liturgy is the centre of the Church’s life and cannot be substituted by, or placed on a par with, any other form of religious expression. Moreover, it is important to reaffirm that popular religiosity, even if not always evident, naturally culminates in the celebration of the Liturgy towards which it should ideally be oriented.

I have made brief mention, at a few points in my ongoing catechesis on the liturgy, of the connection of the rosary with the liturgy. In my previous post, I indicated that the rosary is not, strictly speaking, part of the liturgy. It is a popular devotion. In my estimation, it is the most important popular devotion in Catholicism at present and merits this place by its unique structure. This structure is deeply imbued with liturgical connections.

Let’s begin with the traditional form of fifteen mysteries, over each of which are recited ten Hail Mary‘s. This makes 150 Aves, if one prays the entire cycle of the rosary. This number 150 is also the number of Psalms, and the custom of praying the Hail Mary 150 times derives from the monastic liturgy. Saint Benedict urged his monks to pray all 150 Psalms in a week, noting that the Desert Fathers often strenuously recited all 150 each day. The monastic reformers of the Cistercian order put a greater emphasis on manual labor than had the increasingly wealthy Benedictines of the twelfth century. This had its curative effects, but it also made full attendance at the Divine Office almost impossible. In this circumstance arose the institution of lay brothers, as distinguished from the choir monks. Both groups were monks, but the choir monks were the only ones bound by the full recitation of the Office. The lay brothers did the greater part of the manual work, and in place of the duty of Psalmody, were often permitted to recite a Hail Mary in place of each Psalm (this they could do without recourse to the use of written Psalters; lay brothers did not usually receive the same education as choir monks, and so could be illiterate).

This custom eventually passed, by a mysterious route, further outside the monastery, among confraternities of popular prayer, such as arose in great numbers in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Somewhere around the year 1500, the fifteen Mysteries were added to this basic structure (various precursors had been around since much earlier, but it was in the early sixteenth century that the Mysteries were stabilized). Note that the Mysteries are a mixture of events in the life of Christ and the Virgin Mary. In this, the pious ‘realism’ of the popular movements finds expression. There is a certain drift from the celebration of a more ‘mystical’ Christ, enthroned in heaven, present in the hearts of the faithful, to a more ‘historical’ reading of Christ’s life. We can see this when we compare the list of Mysteries to a list of of the old “Double First Class” Feast Days. I will list the feasts (that were current in the 1564 Roman calendar), along with select Double Second Class Feasts, and hope that you remember what the fifteen mysteries are…

Annunciation

Visitation

Nativity

Purification/Presentation

Epiphany (inc. Baptism of the Lord & Wedding at Cana)

Transfiguration

The liturgical celebration of Epiphany traditional refers not exclusively to the visit of the Magi, but also the Baptism and the Wedding at Cana.

Corpus Christi

[Holy Thursday]

[Good Friday]

[Holy Saturday]

Resurrection

Ascension

Pentecost

Assumption

Holy Trinity

Birth of John the Baptist

Ss. Peter and Paul

St. Michael the Archangel

All Saints

(Bold celebrations do not have a corresponding Mystery; I have grouped these according to the now-four groups of Mysteries, the Joyful, Luminous, Sorrowful, and Glorious; the Sorrowful present certain interesting problems, which is why I did not put the Triduum in bold, nor did I leave this section blank.)

There is a lot to ponder here. A few notes to begin with, and then I will return over the coming week or so to some other observations.

Much as I love Saint Dominic, and much as I am fond of the Dominicans’ love of the rosary, our great saint ‘received’ the rosary more in spirit than in historical reality.

First of all, had St. Dominic in fact invented the rosary, according to the traditional legend, we might expect the Mysteries to match the liturgy even better than it does. That said, the correspondences are pretty good, especially after St. John Paul II’s addition of the Luminous Mysteries, four of which correspond to important liturgical celebrations, two of which (Epiphany and the Transfiguration) have gotten somewhat short shrift in the Western Church of the past millennium.

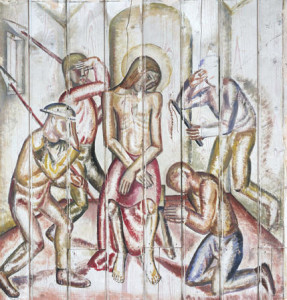

The focus on the life of Christ and an historicization of His life accounts for the Sorrowful Mysteries not quite corresponding to anything specific in the liturgy, aside from the correspondence of Good Friday and the Crucifixion. That said, it is worth noting–and this will be the subject of the future posts of some sort–that the longish meditation on Christ’s suffering really does have an important correlate in the liturgy of Triduum, especially the celebration of Tenebrae.

Finally, for today, it is of interest that the life of Christ in the rosary does not branch out beyond Pentecost into the life of Christ in the Church. That the feast days of saints an angels find no analogy in the rosary might be considered a real deficiency in the connection of the rosary to the Eucharist. Whereas the meditation on the Mysteries of the rosary clearly functions to prepare us for a more full and active participation in the liturgy of the Church, it does not prepare us all that well for the celebration of saints’ feast days, days in which the we celebrate Christ’s ongoing presence in the healing and pedagogic examples of the saints. Nearly all of the omitted Double Second Class feasts are of saints, especially the Apostles (who are understood to be present in contemporary bishops).

The structure of the rosary is not a matter of infallible teaching, and St. John Paul has already given us a certain opening for rethinking the Mysteries. What would happen if we supplemented the present twenty Mysteries with other Mysteria, the sacred mysteries of the liturgy, that do not presently find expression in the rosary? I don’t really know, and I write that to be slightly provocative. I’d be quite interested in readers’ thoughts.

I will share with you some of my own practices regarding praying the rosary, and how I find it helpful to underline the connections with the liturgy. Much to write about here!